Several-dozen Metropolitan Community Church congregants clinked glasses and chatted on the night of June 24, 1973, at the Up Stairs Lounge in the French Quarter of New Orleans. It was a Sunday, just after services. The church that prioritized LGBT-inclusive ministry had tight ties to the bar and would often host benefits there.

One man seemed ornery that night. He’d visited the lounge a few times before, mostly keeping to himself. But this time, he started disturbing patrons. Staff decided to kick him out.

The people inside continued to mingle until about 8 p.m. when someone opened the door to leave. Fire shot up the flammable carpet and smoke poured into the Up Stairs Lounge. The stairwell had become something of a chimney flue that stunk of lighter fluid.

Buddy Rasmussen, who worked at the bar, knew of a fire exit and got about 25 people out. Others tried to slip through the second-floor windows. But there were bars on them to keep people from falling. The Rev. Bill Larson got trapped halfway out the window and died there. His mangled body was visible from the street for hours. Thirty-one others died inside the bar.

It was the deadliest attack on the LGBT community until the mass shooting at Pulse, an LGBT nightclub in Orlando, June 12, 2016 — nearly 43 years to the day after the arson in New Orleans.

No one was arrested in the arson, although investigators focused on one man, Rodger Nunez, who was kicked out of the Up Stairs Lounge before the fire. A man matching his description purchased lighter fluid that same night at a drug store a few blocks from the bar. Nunez committed suicide in 1974.

After his death, a Catholic nun told authorities that Nunez would call her, probably while drunk, and ramble. She said all the problems in his life could trace to the fact that he was gay and having trouble with it.

Others who knew Nunez said he would confess to the arson while under the influence of alcohol.

The fire marshal’s investigation officially closed in 1980. Officials felt the evidence was too circumstantial for a conviction.

‘They maintained dead silence’

Clayton Delery-Edwards was just shy of 16 when he saw the first news reports about the arson in his hometown. He described himself as skinny, nervous and just beginning to realize he was gay. He got bullied in high school.

“I was watching TV and the program was interrupted,” Delery-Edwards said. “It said there was a fire at a French Quarter bar. The earliest reports said it was a ‘hangout for homosexuals.’ I thought, Oh my God, they’re going to kill me. I carried that with me for years. For years, I didn’t come out.”

By the 30th anniversary of the arson in 2003, Delery-Edwards felt ready to reexamine the event that had inspired such fear. He followed coverage of a memorial plaque placed outside the Up Stairs Lounge. Delery-Edwards started talking with survivors. His book, “The Up Stairs Lounge Arson: Thirty-Two Deaths in a New Orleans Gay Bar, June 24, 1973,” came out in 2014.

The author noted the frustration among LGBT residents that civic leaders weren’t speaking out about the tragedy. Mayor Moon Landrieu didn’t say anything publicly for 17 days. Meanwhile, another fire, ignited six months earlier by a Vietnam veteran at a downtown hotel, received continued attention.

“The mayor, governor and archbishop thrust themselves in front of news cameras and called for a day of mourning,” Delery-Edwards said. “Then they maintained dead silence” about the arson at the LGBT bar.

Delery-Edwards’ book details the investigation, which he classed as thorough by the fire marshal’s office if unambitious by police; the press coverage, which was “compassionate” although it outted some people; and the community healing.

Landrieu added openly gay people to the New Orleans human relations commission the summer of 1973. National LGBT activists also descended on the city. The National New Orleans Memorial Fund Collection raised money for victims’ medical expenses.

After the mass shooting in Orlando this year, the attendance at the New Orleans Pride Festival went way up. Delery-Edwards marched with the LGBT+ Archives Project of Louisiana and noticed that every French Quarter establishment had covered its own sign to replicate the sign for Pulse.

“The man next to me said, ‘The people who died in the Up Stairs Lounge would’ve never believed this,’” Delery-Edwards said. “I never thought I’d see it.”

A reverend’s mission

The LGBT community, as a cohesive social or activist body, didn’t exist in New Orleans in the 1970s, Delery-Edwards said. There was some activism at the close of the decade to protest a performance by Anita Bryant, a gay-rights opponent. But the action didn’t lead to any sustained efforts, Delery-Edwards said.

When the Rev. Dexter Brecht with the Metropolitan Community Church assumed the pulpit in New Orleans in the mid-1990s, there still wasn’t much of a sense of a unified community.

“I’m sure you’ve heard the phrase “laissez les bons temps rouler” — let the good times roll — or “laissez-faire” — hands off,” said Brecht, who has since assumed leadership of a Metropolitan Community Church in Delaware County in Pennsylvania. “LGBT people [felt] fine as long as they didn’t make an issue of who they were.”

While reading “Don’t be Afraid Anymore,” a memoir by Troy Perry, who founded the Metropolitan Community Church, Brecht first heard about the arson at the Up Stairs Lounge. He was surprised more people in New Orleans didn’t know about it and decided to memorialize the 25th anniversary in 1998.

Various faith communities and city representatives came together for a service with prayers and speeches. New Orleans City Councilman Troy Carter led the processional from the indoor service to the site of the fire.

The procession took the form of a second line with a brass band that started playing dirge-like music in honor of the 32 people who lost their lives in the arson.

“Then all of a sudden they do what they say, ‘Cut ’em loose,’ to acknowledge that they’ve gone on to a better place and then it’s upbeat music after that,” Brecht said. “It was very fulfilling for me to be able to create a situation where that could happen.”

After the 25th anniversary, the community wanted a more permanent commemoration. Brecht said Larry Bagneris, who had recently been appointed as the mayor’s LGBT liaison, took a special interest in laying a memorial plaque for the arson victims.

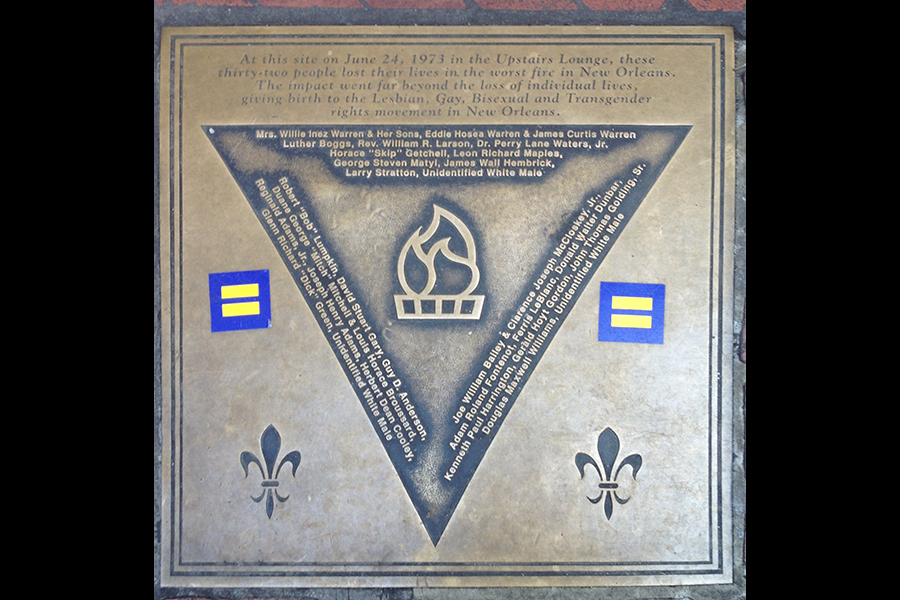

“Larry worked with the city departments and officials to let us put it actually in the sidewalk outside what would’ve been the front door of the bar, which is on a side street,” Brecht said. “It’s actually there in the sidewalk listing all of the people’s names, including the ones that were unknown male.”

Brecht said some bodies were never claimed or too badly burned for identification. He hopes the plaque helps educate young LGBT people about the history of the community.

The local legacy

Today, the space that once housed the Up Stairs Lounge serves as storage for The Jimani, a restaurant that stood underneath the bar since 1971. The current owner, Jimmy Massacci, is the son of the man who started the business.

New Orleans Mayor Mitch Landrieu is the son of Moon Landrieu, who served as mayor at the time of the fire.

Mayor Mitch Landrieu spoke out against discrimination at this year’s Human Rights Campaign Louisiana gala. He referenced pride in “our ability to welcome everybody to the city” when he announced New Orleans would host the 2017 NBA All-Star Game in February. The basketball association decided to move the game from Charlotte, North Carolina, because of that state’s HB2, a law that prohibits local municipalities from enacting LGBT-inclusive nondiscrimination ordinances.

Less than a week after the shooting in Orlando, Mayor Mitch Landrieu held a press conference at which he classified the incident as “an attack on the LGBT community.” He further tied Orlando to New Orleans, saying, “We also had a massive fire in the French Quarter that killed innumerable people that was targeted toward the LGBT community.”

Delery-Edwards said those two cities will forever be linked in the minds of LGBT people.

“Now the fire at the Up Stairs Lounge is the second-deadliest LGBT attack,” he said. “That is a record that should never have existed in the first place, much less have been broken. We all need to be grateful today for the people who weren’t afraid 40 or 50 years ago.”