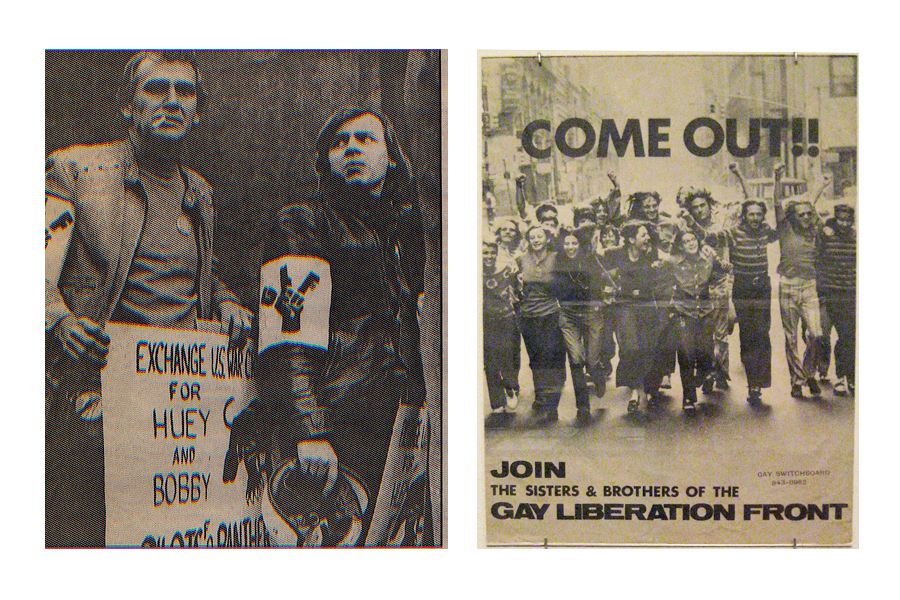

Few instances in the modern movement for gay and lesbian equality (what we now call the LGBT movement) produced as much controversy — and turmoil — as the New York Gay Liberation Front’s relationship with the Black Panthers, a late 1960s-early 1970s radical organization that stood for the complete overthrow of the capitalist American government to achieve equality for African-Americans.

The Gay Liberation Front was the first and most radical organization to be formed after the Stonewall Riots (or Uprising) in June of 1969. I joined GLF in mid-November 1969, and by this time there was already a definite, but not always comfortable, relationship between the two groups. For many GLF people, the Panthers were a complete model for their own politics; both groups wanted revolutionary changes in society to effect equality for all citizens, but in particular the constituents of these two groups: African-Americans and LGBT people.

The Panthers had many branches: a social-services wing, providing breakfasts and a literacy program for poor black kids; a publishing and propaganda branch to publish Panther papers and manifestos; a military branch that planned armed rebellions against the police and the U.S. government; and a political branch that organized conferences and meetings. It is difficult to imagine in this time of social networking and, too often, cosmetics-deep “celebrity” politics, any organization as dedicated to complete rebellion as the Panthers, or for that matter the Gay Liberation Front.

And, at the same time, to imagine any two organizations working together that fit less comfortably with each other.

The Gay Liberation Front took most of its cues from feminism and the feminist movement. Many of its leaders were lesbians who later formed another group of their own, Radicalesbians. The Panthers tried to uphold a street-savvy, macho, male-dominated image that often contradicted the reality that women, in the face of so much violence from the police (the “pigs” in 1960s parlance), did hold the Party together. Nevertheless, this inspired Black Panther Party leader Bobby Seal’s famous quote about the position of women in his organization: “The position of women in the Black Panther Party is prone!”

A short time after I joined GLF, an inner circle in the group floated a proposal that was even more controversial than usual: As a revolutionary act, “in support of our black sisters and brothers,” GLF should donate $500 to the Panthers. (To give you an idea of how much money that was, rent on my rent-controlled, Hell’s Kitchen fourth-floor walk-up apartment was $73 a month.)

The money was raised by a weekly gay-community dance at Alternate University, a large space on 14th Street and Sixth Avenue that was home to many radical organizations and their activities. Admission to the dances was $1.50.

The dances were put on by a “cell,” or committee, of GLF that was itself split by this proposal. Some cell members felt that the money, since it came from the community, should only go back to it. There were young street queens sleeping on sidewalks or out on the piers on the Hudson; older gays and lesbians struggling to eat; and, also, an idea floating around that we should start our own community center. In addition, many lesbians felt that our money should be directly supporting feminist causes, like upholding abortion rights or providing shelters for abused women.

Bob Kohler, an older very “alpha” leader of the pro-Panther faction (he was in his mid-40s; I was in my early 20s), gave an impassioned speech to the overwhelmingly white GLF membership, exhorting us that we had to give the money to the Panthers. “Think about every time you ever used the word ‘nigger’ or ‘spic,’ every time you yourself ever oppressed black people just by being white in a racist world. Think about that. That is why we need to give this money to our sisters and brothers in the Panthers.”

There was more discussion, but we finally agreed and a check for $500 was given to them. It was a turning point in this explosive period of gay politics. A lot of older, old-school activists who had been Mattachine Society members were self-righteously sure this was going to be the last nail in the coffin of the rambunctiously youthful Gay Liberation Front: These self-styled gay “radicals” were only trying to buy a politically correct version of “righteousness” — wrapped inside a distorted mirror-image of tough street credibility — by funding an organization that was from the outset under constant police surveillance. It fanned a smug reaction also within the broader gay community itself, that still shared an attitude that everything to do with blackness was outside us — and outside most “normal” human feelings as well.

The gift also spurred a rush for some politically active men to join the Gay Activists Alliance, a newer competing group started by ex-GLFers who only wanted a single-issue, gay-focused organization that would appeal basically to white, middle-class men.

A short time afterwards, Huey Newton came out with a speech that on one hand delighted some GLFers, while infuriating others. He said about women and gays that, because of the depth of their oppression, they could be as “revolutionary as anyone, maybe even more so,” despite the fact that, for many black men, their first gut reaction with women was “to tell them to shut up,” and with gays was, well, to — “punch them in the face.”

This speech became a litmus test for many GLF men and women. It was as if Newton had given us some recognition and spit on us at the same time. In some ways, it only reinforced an image of rampant black rage toward others, reflecting, still, the endless psychological and physical oppression of black men and women.

Steve Gavin, who worked with me on the GLF newspaper “Come Out!” was particularly livid. He called the donation to the Panthers and the adoration of their macho image “oppressor-sucking.” He had come, as I did, from an impoverished background, and scoffed at many of the GLFers from comfortably middle-class origins “sucking up to the same people who oppress us.” The gift to the Panthers did cause many women to drop out of GLF, and some men to feel that we were only playing at radicalism, using a checkbook instead of walking dangerous picket lines and openly confronting the cops about violence in minority communities.

What they did not see was that this was the first time that an open and actively gay organization had embraced another oppressed group, as part of recognizing a common oppression with them. The history of the Black Panthers in the U.S. was horrifying. Many of them were shot down by cops, had their homes burnt out or bulldozed, were imprisoned on phony narcotics charges, had their mail and phones tampered with and were never given credit for the good they did, at a time when it was considered normal for African-Americans to live in subhuman conditions.

GLF made a practice of standing with two Black Panther women held inside the infamous Women’s House of Detention on Greenwich Avenue in the West Village, on the other side of the Jefferson Market Courthouse, which later became the Jefferson Market Library. GLFers participated in weekly vigils and protests at the Women’s House of D. The women were Angela Davis and Joan Bird. Bird was arrested in 1970 at the age of 19 for being part of the Panther 21: 21 members who were accused of trying to blow up buildings in the Bronx, including the Bronx Botanic Garden. All 21 of the Panthers were acquitted. Bird was held in the House of D for months. Davis, a brilliant political theorist, actually was not, but the vigils outside the women’s prison were for both women, as well as for all the women inside. Davis was arrested in New York after being implicated in Panther George Jackson’s escape plot from a courthouse in Marin County, Calif. Jackson became the subject of Bob Dylan’s mournful dirge “George Jackson,” which became a hit song of the civil-rights movement. Davis was later tried in California and acquitted of all charges, but not before spending many months behind bars there.

We now understand that Black Lives Matter. The truth was the Gay Liberation Front understood this in 1970.

Perry Brass’ 19 books include fiction, nonfiction, poetry and short stories. His latest nonfiction book is “The Manly Pursuit of Desire and Love” and latest novel is “King of Angels,” a gay coming-of-age story set in Savannah, Ga., in the Kennedy era. His work often deals with the heartfelt feelings of men and women that came from his radical roots in New York’s Gay Liberation Front. He is a founding coordinator of the New York Rainbow Book Fair and writes often for the Huffington Post. More info: www.perrybrass.com.