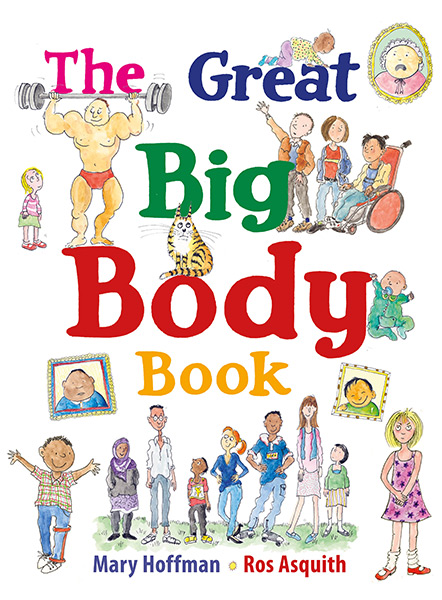

A new children’s picture book about human bodies includes transgender and gender-nonconforming people as well as same-sex parents. That’s a rare and wonderful thing, making this a welcome book, despite a few caveats.

“The Great Big Body Book,” by English author Mary Hoffman, is the fourth in her Great Big Books series for preschool and early elementary-school kids. An earlier book in the series, “The Great Big Book of Families,” showed families with same-sex parents, among others, and Hoffman brings the same inclusive sensibility to her new work. “The Body” book begins by asking “What is a body?” and goes on to explore, in a fun and lighthearted way, how our bodies grow and develop over our lifetimes and the many things our bodies help us do.

Lively illustrations by Ros Asquith highlight the main text and the humorous side vignettes that show short dialogues among the diverse characters. Several wear headscarves and one wears a turban. We see two-dad, two-mom and single-parent families. There are characters with a variety of physical disabilities, too, including ones in wheelchairs, one using a walker and one with a short arm. To Asquith and Hoffman’s credit, they are always shown doing active things — they are not there as examples of harm or limitations to bodies.

In one spread, “Boy or Girl,” Hoffman pokes fun at the obsession with babies’ genders. One mom on the page, when asked “What is it?” responds simply, “A baby.” A dad is asked “What’s her name?” and answers, “Fred.” Hoffman notes that pink doesn’t have to be for girls, nor blue for boys.

She then observes, “Some bits of your body are different, according to whether you are male or female.” That stays the same for most: “If you are born a boy you become a man and if a girl, you grow up to be a woman.” A few people, however, “don’t feel completely comfortable in the body they were born in and not everyone fits neatly into a ‘boy’ or ‘girl’ box. That’s OK — just be yourself.”

Overall, it’s a positive, simple explanation of being transgender or gender-nonconforming. Hoffman doesn’t use those terms, however, which could be seen as a negative. At the same time, she never uses the word “puberty” despite discussing the changes teens go through, so this may be part of an overall decision to focus on concepts more than terminology — or perhaps a praiseworthy desire to avoid labels.

This brings us to the section on teens, in which Hoffman notes that “Boys’ voices get deeper and they start growing hair on their faces and private parts. Girls grow breasts and their hips get wider. They get hair in private places too.” That’s not true for all trans teens, of course, especially if they are not using hormones. I would have preferred a more nuanced view, perhaps simply by adding “most” before “boys’” and “girls.”

I also have concerns with a spread explaining that having a baby bump is not the same as being fat. Several pregnant women are shown at the top of the page. One of the side vignettes, which usually contain funny comments about the topic at hand, shows a boy pointing to a person with a beard and a large belly and saying, “Look! He’s having a baby!” The message seems to be that if a male-appearing person looks pregnant, it’s funny — a mistaken assumption. The humor is vague enough, however, that the image could also be interpreted as an actual trans dad, if desired (and alternatively, the character has gray hair, so maybe age is the intended butt of the joke, not gender), but a different vignette might have been better.

I’m also iffy about the page on families, which explains that our looks and maybe how our senses work “depend partly on our parents and grandparents.” There’s no acknowledgment of the many children who, through adoption, surrogacy or assisted reproduction, have no genetic ties to one or more of the parents raising them. Granted, this is not a book about reproduction, and is aimed at an age group that may not yet know about it — but I would have preferred “may depend” rather than “depends partly” — or simply, “Some people look like their parents. Others don’t.”

The book begs comparison to the trans- and gender-nonconforming-inclusive books “What Makes a Baby” (for pre- and elementary-school children) and “Sex Is a Funny Word” (for 8- to 10-year-olds) by Cory Silverberg and Fiona Smyth. Silverberg and Smyth focus on sex and reproduction, rather than taking a broad look at bodies. They manage, however, to be completely inclusive of all gender identities, noting, for example, that “some bodies [never specified by gender] have a uterus and some bodies do not.” Hoffman never reaches this level of integration.

Nevertheless, to see the positive inclusion that she does have in a book from a mainstream publisher (Frances Lincoln, part of the Quarto Group) is remarkable. Her more-moderate approach may even get her book into the hands of some people who are not yet comfortable with the total inclusiveness of Silverberg and Smyth’s work. Despite its limitations, then, “The Great Big Body Book” will be a valuable addition for many families as well as schools and libraries.