Transgender actress Laverne Cox remembered sitting in a therapist’s office in Alabama when she was around 8 years old. The therapist asked if she knew the difference between a boy and a girl.

“In my infinite wisdom as a third grader,” Cox said, “I said, ‘There is no difference.’ This was years before [I read] Judith Butler or any kind of gender theory. But the way I reasoned it in my mind at the time was that everybody was telling me I was a boy, but I knew that I was a girl. I knew it in my heart, my soul and my spirit; I was a girl.”

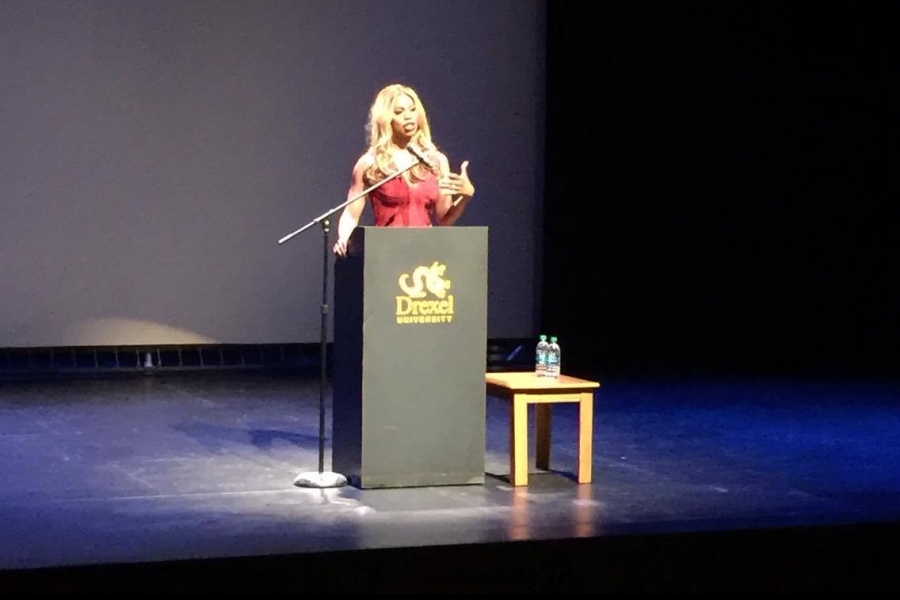

Sounding like a spoken-word poet through her hour-long speech, Cox dazzled the 420 people packed May 10 into Mandell Theatre at Drexel University. She spent another 20 minutes on audience questions. The Student Center for Inclusion and Culture sponsored the event, along with the Campus Activities Board.

It was a full house for the “Orange is the New Black” star, and a portion of the night’s ticket sales benefited The Attic Youth Center.

“Laverne Cox continues to make history in her career and significant strides in her activism,” said Sarah Olsen, assistant director of campus engagement at Drexel, at the opening of the talk. She went on to call Cox “an advocate with an empowering message of moving beyond gender expectations to live more authentically.”

Cox is the first trans woman of color to have a leading role on a mainstream scripted show. The fourth season of “Orange is the New Black” comes out June 17. Cox has also been working on a forthcoming CBS legal drama, “Doubt,” and plays Dr. Frank-N-Furter in “The Rocky Horror Picture Show,” set to air on FOX in the fall.

She said the trajectory of her career changed once she stopped viewing her transgender identity as something that might hold her back.

“I stand before you this evening a proud African-American transgender woman from a working-class background raised by a single mother,” Cox said. “I stand before you an artist, an actress, a sister and a daughter … I believe it’s important to claim the various intersecting components of my multiple identities with pride in public. I haven’t always been able to do so.”

Cox had the tone of a beloved professor when she talked about shame and the work of Dr. Brené Brown on the subject. Feminism was also a hot topic. Cox has clearly spent time doing what many would consider the required reading.

She peppered the phrase “ain’t I a woman” throughout her talk as a kind of refrain, in reference to the famous speech given by civil-rights activist Sojourner Truth at the Ohio Women’s Convention in 1851.

Cox also repeated “trans is beautiful,” along with “One is not born a woman, but rather becomes one,” and “Nowhere … is it guaranteed that the one who becomes a woman is necessarily female,” from the feminist manifestos of Simone de Beauvoir and Butler, respectively.

She discussed a disagreement she had with black feminist Bell Hooks about the value of female presentation, noting feminism has a history of painting femininity as artificial and masculinity as authentic.

“My femininity is something that I’ve had to fight for,” Cox said. “I was terrified of being as feminine as I was. When I finally just let go and was like, let me embrace this, it felt so freeing. What might be shackles for one woman is liberating for another.”

Cox weaved her own stories into the analysis of gender.

She talked about attending the Alabama School of Fine Arts where she practiced “Salvation Armani,” turning thrift-store clothing into her own couture, and eventually moving to New York City in the 1990s to attend Marymount Manhattan College.

Cox started her physical transition in New York, receiving hormone therapy and wearing the dresses she didn’t feel she could in high school. Three years into her transition, she thought she would be able to walk down the street and no one would know she was trans. That wasn’t the case, she said, but she came to love her big hands and feet and her height. Still, she encountered violence.

In 2008, a group of men in Midtown Manhattan kicked her and shouted anti-trans slurs as she tried to pass them.

Thirteen years ago on the Fourth of July, Cox was walking to the train station in her Upper West Side neighborhood when a red light stopped her at a corner with a Latino man and a black man. One man tried to hit on her. Then the two began arguing about whether she was a man or a woman, using the “n-word” and the “b-word,” Cox said.

“I’m just standing there waiting for the light to change, like, ‘God, get me out of here,’” she said. “I got out of that situation safely.”

Cox paused to say the name of Islan Nettles, a black trans woman who was pummeled to death in Harlem in 2013 after the man who hit on her realized she was transgender. Nettles’ attacker, James Dixon, pleaded guilty to manslaughter in April.

Cox also recognized the support system that her mother has become for her. Her mother did try to get Cox to identify as a boy when she was young. But her mother drew the line when a therapist suggested injecting Cox with testosterone to make her act more masculine.

As an adult, Cox sent her mother books, articles and videos about transgender people to help educate her.

“We had a lot of difficult conversations, arguments often, about the right pronouns to use to refer to me in public and in private,” Cox said. “It was hard. But we got there. I’m very lucky that my mom has always wanted me in her life. She’s never said, ‘You can’t be in my life if you do this or that.’”

“Having her accept me as her daughter has been one of the greatest blessings of my life,” Cox added. “We got there being willing to have difficult conversations across difference.”