Queer sexuality, the African-American experience and Modernism mix in thoughtful, inspiring ways in “Carl Van Vechten: O Write my Name — Portraits of the Harlem Renaissance and Beyond,” a new exhibit at Haverford College.

The show, which runs until Aug. 19, is free and open to the public. It is on display in the Sharpless Gallery of the Magill Library at Haverford, a prestigious liberal-arts college on the Main Line.

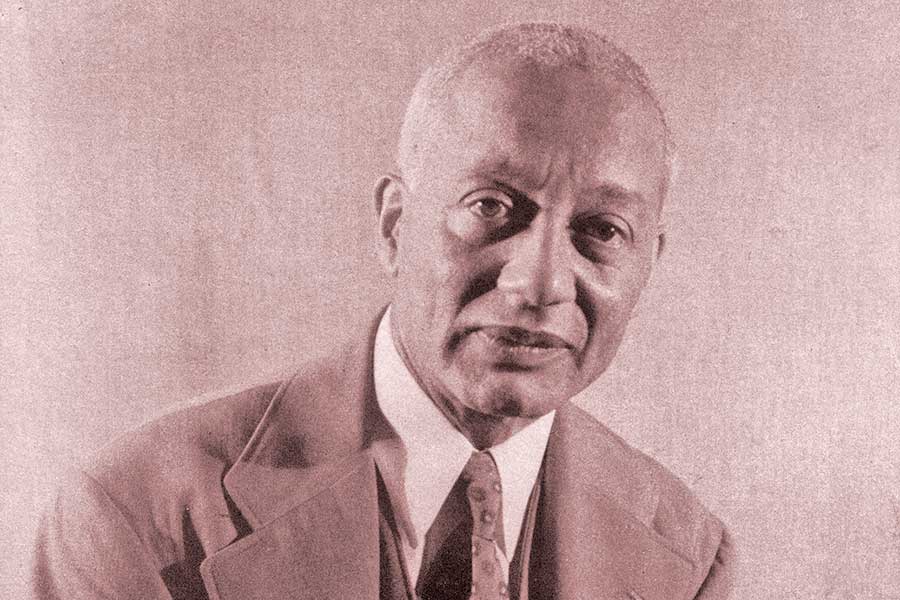

The exhibit was curated by William Earle Williams, the Audrey A. and John L. Dusseau Professor in the Humanities. It includes books, letters and prints, but its core is 50 portraits of distinguished African-Americans photographed by Van Vechten.

Van Vechten, born in 1880, was immersed in Modernism, an experimental artistic movement of the early 20th century. An avant-garde polymath, he was a dance critic, music reviewer and novelist. In the early 1930s, he stopped writing to concentrate on photography. By the time he died in 1964, he had made roughly 15,000 photographs.

This exhibit, according to Williams, gathers “50 pretty terrific images that he did, which is representative of his total project, which was extremely ambitious, which was to photograph the Western avant-garde.”

Van Vechten’s personal life was as varied as his artistic interests. Although married twice, he had numerous affairs with men, which were an open secret within his circle.

One thing that distinguishes Van Vechten from his colleagues in the international avant-garde, like surrealist Man Ray and experimental author Gertrude Stein, was his deep appreciation of African-American culture.

“He’s special because he also saw, as a vital part of the avant–garde, the African-American experience,” Williams said. “I think one of the ways he came to appreciate how vital that was is because he was involved with dance, theater and the visual arts.”

Among the displayed portraits are actor Ossie Davis and singer Ella Fitzgerald. Van Vechten also photographed artists and thinkers associated with the Harlem Renaissance, which flourished from 1918-37, and which Williams described as when “Harlem burned or shone brightest on the cultural scene.”

In addition to the art and ideas that emerged from the Harlem Renaissance, the movement fostered a tolerant atmosphere. The frank, open expression of LGBT sexuality was not uncommon. As scholar Henry Louis Gates Jr. wrote, the Harlem Renaissance “was surely as gay as it was black.” In this exhibit, viewers can see portraits of poet Countee Cullen, blues singer Bessie Smith and philosopher Alain Locke — all LGBT individuals associated with the Harlem Renaissance.

Some of these portraits have become the most well-known images of the sitters. “The Zora Neal Hurston photograph, and the Jacob Lawrence and Bessie Smith, those are all iconic images of those artists,” Williams said.

Van Vechten’s portraits aren’t interesting just because of his subjects’ accomplishments or fame; he also had considerable technical skill. Williams, a photographer himself, praised this aspect of Van Vechten’s work.

“In terms of the formal language, that part of it, Van Vechten’s a master of lighting, backdrops, the poses.”

His portrait of the choreographer Katherine Dunham is a good example. Because of her costume, Dunham seems to blend into the theatrical backdrop behind her, but her eyes, alert and vivacious, signal energy and movement.

Of course, technical facility by itself doesn’t guarantee an artistic outcome. For that, something more is required. In Van Vechten’s case, it may have been a very human element: respect.

By all accounts, Van Vechten genuinely admired the men and women he photographed. He championed their work and helped them make influential connections. Some of his sitters, like the poet Langston Hughes, himself a gay man, became lifelong friends.

For Williams, that relationship is crucial. “There’s an exchange between those two, and it’s one of respect. And an equality,” he said.

This mutual respect produced excellent results. “If you look at any of these people’s pictures, there’s a wonderful kind of physicality to them that you don’t get any place else in terms of their portraiture than with Carl Van Vechten.”

How Van Vechten’s sexuality influenced his art remains an open question. Williams, for one, does not think it should be dismissed.

“Van Vechten was a very complex person, and part of his complexity was his sexuality,” he said.

In fact, Williams believes Van Vechten’s sexuality may just have made him alert to possibilities that conventional taste and prejudice prevented others from seeing.

“There certainly is a sensitivity that’s there and some might refer to it as a ‘gay gaze’ or a ‘queer sensibility’ there, but that’s, again, only part of the work, which I think makes it that much more engaging,” he said.

For more information on the Van Vechten exhibit, visit ow.ly/YHVo7.