When Joseph Israel Lobdell passed away in 1912 at the Binghamton State Hospital, his death went largely unnoticed. Joe, as he was known, was 82 and had been confined to mental institutions since 1880. In the intervening decades, his siblings had predeceased him.

In his lifetime, Joe was a crack shot and a wonderful fiddle player. He opened a singing school and, for a while at least, found modest success with that business. There was some adventure in his life, too. Joe traveled west to Minnesota, where he guarded land on the frontier.

Within the context of 19th-century American social history, experiences like these were not uncommon, but one aspect of Joe’s life is extraordinary: He was born in 1829 as a woman, Lucy Ann Lobdell.

Although Joe Lobdell died in obscurity, he’s recently begun to attract attention. In 2011, for example, Dr. Bambi Lobdell, a distant cousin, published “A Strange Sort of Being: The Transgender Life of Lucy Ann/Joseph Israel Lobdell, 1829-1912.” And earlier this year, journalist William Klaber released a novel about Lucy/Joe, “The Rebellion of Miss Lucy Ann Lobdell.

It seems as if Joe’s time has come.

Dr. Lobdell, who teaches gender studies and literature at SUNY Oneonta, certainly feels that way. Her book includes both an analysis of Joe’s life informed by queer theory and transgender studies, as well as primary documents about him.

Dr. Lobdell regards Joe as a gender outlaw and argues that he is best understood as a transgender man. She acknowledges that this category was unavailable to Joe, but she believes that it most closely approximates his understanding of himself and restores a modicum of dignity to him.

“I use the word transgender, in its widest application, to mean not cisgender and not gender-conforming,” she said.

For Dr. Lobdell, this isn’t simply an academic exercise. She contends that many of the issues confronting Joe, including societal expectations and gender roles, are still relevant to LGBT people.

Joe’s history is important, Dr. Lobdell explained, because “it tells a story of how his otherness was framed as deviance and how his otherness was basically signaled by his gender presentation, his refusal to conform.”

“So he crossed the boundaries of gender roles and gender presentation and sexuality, though the people back then didn’t realize that, because most people, including women in the 19th century, thought that women didn’t have any sexual desire.”

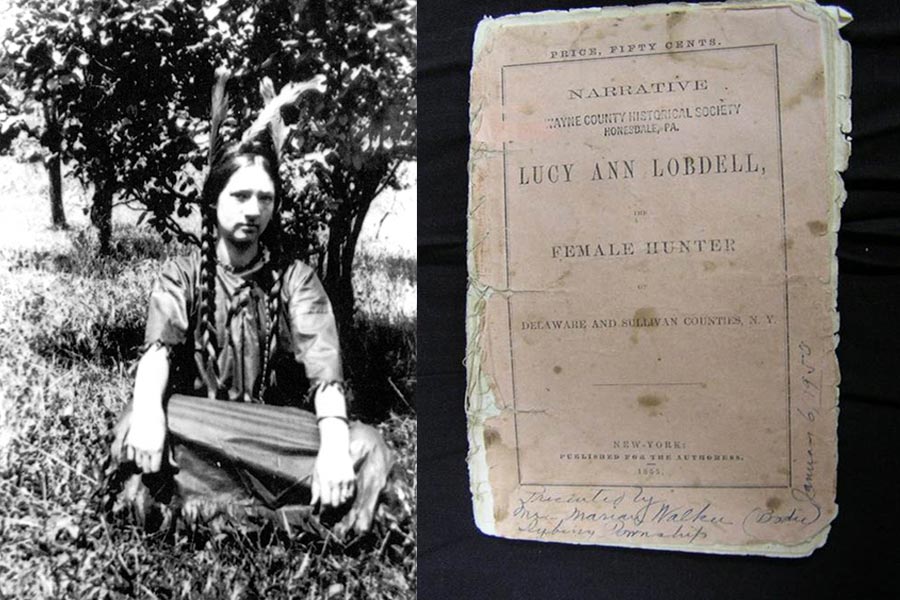

Fortunately for scholars, there are contemporary, written accounts of Joe’s life. Chief among them is a book Lobdell published in 1855: “Narrative of Lucy Ann Lobdell, the Female Hunter of Delaware and Sullivan Counties, N.Y.” In a 2012 podcast with Susan Rich, Dr. Lobdell described it as part-melodrama, part-feminist manifesto.

One immediate result of the book’s publication was a measure of notoriety for its author. The “Female Hunter” became fodder for journalists. For the remainder of his life, whenever Joe ran into trouble, periodicals like The Stamford Mirror and The Jeffersonian mentioned the “Female Hunter.”

Copies of the narrative are rare. Fortunately, Dr. Lobdell includes it in its entirety in “A Strange Sort of Being.” That’s partly because Dr. Lobdell conceived of her work as an academic textbook that could be adopted for college classes in gender studies and sexuality. “I just packed it full of all sorts of gender theory and gender analysis and queer theory,” she said when asked to sketch its contents.

Within Lucy’s narrative, there are a few agreed-upon facts worth noting. To begin, Lucy Ann Lobdell was born Dec. 2, 1829 just outside of Albany, N.Y. The family was poor, but Lucy wanted an education. To pay for schooling, she was given some chores. That was how she learned to shoot, a skill she put to use at various times later in life.

Around 1852, the Lobdell family moved to Long Eddy, N.Y. Roughly a year later, Lucy married a man named George Washington Slater and gave birth to a daughter. Her account depicts an unhappy marriage. When Slater abandoned them, Lucy returned to her family, left her daughter with them and slipped away one evening in 1854.

Shortly afterwards, Joseph Israel Lobdell appeared in Bethany, Pa., where he opened a singing school. From this point forward, details of Joe’s life can be pieced together, if sketchily, from occasional newspaper accounts or court documents about him.

In retrospect, it appears that the writing and publication of Lobdell’s narrative marks a significant transition. For the remainder of his life, more than five decades, he uses the name he’s chosen for himself and dresses as a man — except on those occasions when a sheriff or deputy tried forcing him to wear women’s clothes.

The singing school attracted students, most of them the daughters of well-to-do farmers and businessmen from the provincial town. There is some evidence that Joe was well-liked by his pupils. According to Dr. Lobdell, someone once interviewed the descendant of a woman who had attended the school.

“Apparently, a lot of women danced with Joe when he was a singing teacher,” Dr. Lobdell said. “And this one woman said she remembered her grandmother saying, ‘I can’t believe that’s really a woman; he was the nicest boy I ever dated.’”

Problems arise, however, when Joe’s “identity” is revealed. He is chased out of Bethany by a mob threatening to tar and feather him.

Undaunted, Joe heads west, arriving in Minnesota. Here he sometimes goes by the name La-Roi. In Minnesota, Joe works odd jobs and even guards land for its owners. Joe’s physical courage should be noted: Minnesota’s winters were harsh, he was living on the edge of the wilderness with only his rifle to protect him, and clashes with Native Americans were always a distinct possibility.

Once again, however, Joe’s “identity” is revealed. After a trial, Joe is sent back east to his parents’ home. Depressed and unable to find work, he enters the County Poor House in Delhi, N.Y., in 1860.

It’s there, roughly a year later, that Joe meets Marie Louise Perry. Marie, who had been abandoned by her husband, arrived physically weakened and emotionally upset. Joe helps nurse Marie back to health, which restores his spirits, too. One night, the two escape from the Poor House and are married by a Justice of the Peace. Joe now has a bride, a woman about a decade younger than him.

Joe and Marie are together for almost 20 years, but their life is not easy. They eke out a living doing odd jobs or survive on whatever food Joe’s hunting provides. Often, they live outdoors in the thick woods of upstate Pennsylvania and New York. The couple is desperately poor and, consequently, always in imminent danger of being arrested for vagrancy.

Joe’s life takes a turn for the worse around 1878. Shortly after receiving a Civil War pension (Slater was killed in the war), Joe’s brother has him declared insane. In 1879, he is taken away to the Willard Insane Asylum in Ovid, N.Y.

While locked up, Joe becomes a patient of Dr. P.M. Wise, who publishes a brief article about Joe in 1883. In that account, entitled “A Case of Sexual Perversion,” Dr. Wise relates a telling statement from Joe. The patient, whom he insists on viewing as a woman, tells him that “she considered herself a man in all that the name implies.”

Dr. Lobdell thinks we should take Joe at his word, something she views as paramount.

“What I’m trying to do is give Joe back his voice, because — and this is another way it should resonate with people today — transgender people oftentimes are not allowed to tell their own story.”

To learn more about Joe Lobdell, visit www.lucyjoe.com.

Ray Simon is an editor and writer based in Philadelphia who contributes articles on arts and culture to Philadelphia Gay News and other publications.