Philadelphia playwright Melissa McBain created a play that hits hard: Maggie, an adoring Pastor’s daughter, eventually speaks up, not only for her gay son, but challenges the assumptions of a “holy” book that was written by tribal men in a desert culture more than 2,000 years ago.

Unlike many other coming-out plays, “Altar Call” goes deeper. It shows the conflict with which each character struggles, performed by a fine cast. Even though it is a modern tragedy, directed by William Andrew Robinson and produced by Random Acts of Theater, it’s ultimately a dramatic, and not so random, act of kindness.

The play takes place in a Baptist church and an upscale home in an Arizona desert. Unlike the Catholic Church, where the hierarchy at the Vatican makes decisions, the Baptist Church follows a different model where pastors have much more leeway in their decision making — an important part in the conflict-laden family of a bright and well-meaning, but ultimately bigoted and homophobic, minister.

Right from the beginning, we hear the voice of tradition, mediocrity and hate setting the stage. Howard (Ben Kendall), a senior church member, berates Pastor Silas Elmore (Russ Walsh) for supporting “perverts.” When the homophobe doesn’t give up, the pastor delivers a brilliant coup de grace: “Theologically speaking, have you ever considered going to hell?”

Ruth (Susan Mattson), the pastor’s wife, argues with her husband about their grandson, John (Gil Johnson), whom he considers “so weak.” Foreshadowing the events to come, the pastor tells his wife, “I’m just being vigilant.” When Maggie (Julia Wise) tells her father about Matt (Peter Andrew Danzig), the young new musician who is tutoring John, the pastor, full of suspicion, asks, “How often are they alone?” He quotes Leviticus, Chapter 18.

Maggie, still under the spell of her father, confesses that she always loved his sermons, “whether they were good for me or not.” Right from the beginning, we realize that the main character is a bright woman who is going to come into her own, even though she will be tried severely by everyone in the play.

Her father reverts to traditional interpretations, especially when it comes to women and minorities. When John, the minister’s grandson, falls in love with Matt, he has to be fired — an act that leads to not only the break-up of the family, but to many insights about the negative impact of dysfunctional traditions. “We’re next in the cross hairs,” he admits, and later tells the young musician, “You’re hurting this ministry. And now my family.” Matt, outraged, asks, “Aren’t they the same? You made me part of this family.” Convinced that he is doing the right thing, Silas tells his grandson that firing the young organist “saved him! And you!”

Yet, the same man who powerfully interferes in the life of his gay grandson tries to whitewash the digressions of Alan, his heterosexual son-in-law (Andy Joos): “Maggie, don’t be so suspicious. It’s unattractive.” Dutifully, but also honestly, she tells him, “I’m trying, Dad, but it’s a lot of work being blind.”

Pastor Elmore, who appears as the epitome of open-mindedness, can be as narrow-minded as any homophobe when he learns that several of his colleagues have lost their ministries because they had affirmed homosexuals. “Liberals don’t give money to churches anymore. They save trees and animals. Not souls. They’ll picket to save an old theater or rattlesnake but not a church. White liberals anyway. Don’t they build churches with closets anymore?”

Full of defiance, Maggie tells her mother of her husband’s extramarital affairs and then declares, “I don’t want a family glued together with lies.” At that moment, her mother, a traditional wife who often sounds like a religious doormat, has her own breakthrough, telling her daughter, “Then you stand up and tell the truth! Pull out the lies, one thread at a time. Then you put what’s left together. You make a quilt.”

After previous performances of her play, McBain received moving letters from grieving parents whose gay kids no longer could endure the constant harassment and abuse from classmates and neighbors. One mother wrote, “I don’t have a gay son; I have a dead one.”

Edward Albee read the script and liked it so much that he recommended it (“you should see this play”), a testament to the power of “Altar Call” — it could open minds, inside and outside of churches.

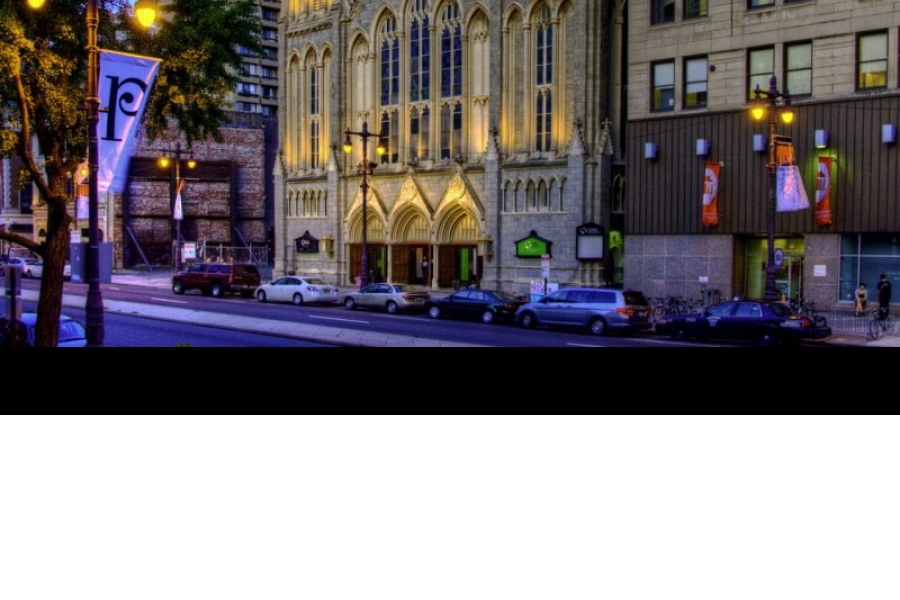

“Altar Call” is being performed at Broad Street Ministry, 315 S. Broad St. at 6:30 p.m. Oct. 17 and 2 p.m. and 6:30 p.m. Oct. 18. For tickets, click here.