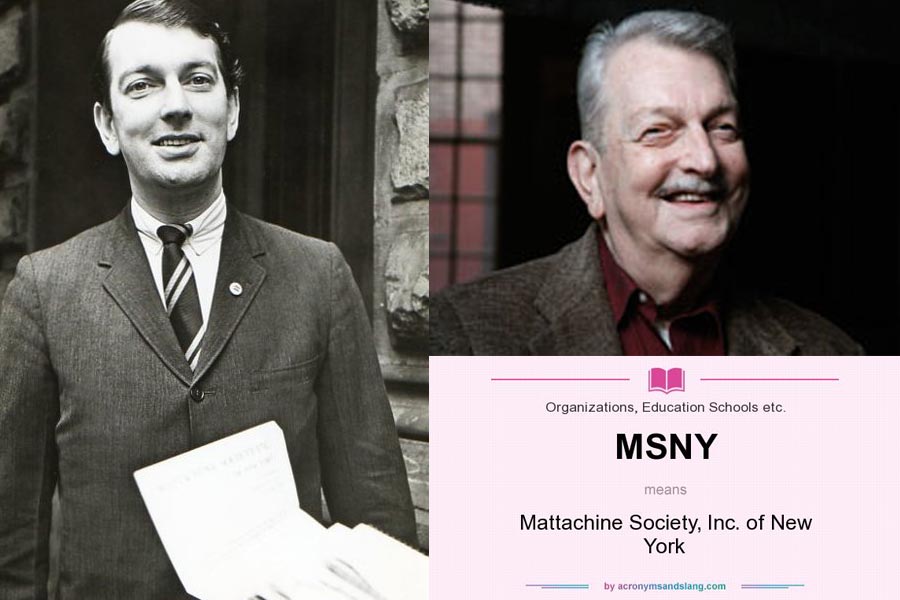

For my friend Dick Leitsch, the last president of the Mattachine Society of New York, who last May turned 80, history was unavoidable.

I met Dick in two different periods of my life. At 20, I attended my first and only meeting of the New York Mattachine Society, at the old Wendell Wilkie House near Bryant Park in New York City. He moderated, handsome, stylish, with a soft-spoken Kentuckian polished air. I was turned totally off: Mattachine was strictly out of my world as, new to New York, I struggled to make sense of myself. Two years later, a few months after Stonewall, I joined the Gay Liberation Front. GLF offered me a valid political understanding of why queers were being destroyed in American society, and what we had to do, often rowdy as we were, to change it.

Both Dick and Mattachine were loathed by many of my young GLF brothers and sisters, some of whom had been in it and, like unruly kids, resented their dowdier parents.

Dick was often referred to as “Pig Leitsch.” For us, he represented gay accomodationists, what we called “dragonfaggots,” “Aunt Sallies,” queer “Uncle Toms.” His very image seemed like a ghost from the 1950s and mid-1960s. Then in 1975, I started freelancing for Countrywide Publications, a scrappy pulp magazine conglomerate on lower Park Avenue, run by the infamously cheap Myron Fass and his brother (often described as “borderline-personality” types for their explosive dealings with employees), who presided over a farm team for a later generation of successful writers and editors. My editor was Robert (Bobby) Amsel, a gifted young man editing a group of low-end, hetero porn magazines often written by hungry gay scribes like myself. Bobby and I became close; he literally taught me how to write for commercial publication. He revealed that his long-time partner was Dick Leitsch, “president of the old Mattachine Society.”

I blinked twice. Bobby had actually had a history with Mattachine, and after Stonewall, as Mattachine was folding, became president while Dick remained executive director. I soon met Dick again, and quickly adored him. He was a throwback to another era, of courtly Southern gentlemen (he’s from Louisville) and old-school gay-bar queens, denizens of a complete culture of gay bars, something that younger people now find difficult to understand. For decades, gay bars were our most visible institutions. Gay men and lesbians found their only home in them. In New York, bars were raided cyclically: usually before elections, before major events like the 1964 New York World’s Fair when Mayor Robert F. Wagner Jr. closed the bars to keep innocent tourists from wandering in (like, what were they going to do in them?), or when cops decided they wanted to squeeze out a bit more payola from mafia barkeeps.

This was fostered by New York’s state alcoholic beverage agency, which had rules dating from the 1920s against serving homosexuals “openly” in any bar. In 1966, Leitsch, along with other members of NY Mattachine, staged the “Sip-In,” the first “out” gay demonstration in New York state history. They walked into Julius’, an oft-raided bar on Waverly Place in the West Village, declared themselves gay and were immediately refused service. The event was recorded in Fred W. McDarrah’s famous photo showing Dick in profile next to Craig Rodwell (soon to open the Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookstore, the first gay bookstore in the United States) and long-time activist Randy Wicker. Mattachine took Julius’ and the state agency to court, paying the bar’s legal fees because, as Dick put it, “We just wanted to make a case, not punish them.” A New York judge declared that the state’s policy denied gays their basic right to free assembly; the rule was unconstitutional. But this did not stop gay bars from being harassed, and three years later a June raid on the Stonewall Inn in the Village exploded as no one thought it would.

Dick told me he never thought of himself as being political; he was simply for “our right to exist.” For close to a decade before Stonewall, he was one of a few openly gay men in America. To be that open, he’d had to take a virtual vow of poverty, and for several years lived rent-free in a room in a spacious rent-controlled apartment leased by Madolin Cervantes, a straight woman and Mattachine officer who loved gay men. To make money, as a solitary advocate for gay rights, he got sent out on college lecture circuits where he met the Beat poet Allen Ginsberg, America’s second openly gay man.

“We would criss-cross each other on college campuses,” Dick told me. “We became friends. He published stuff in Mattachine publications.”

Dick worked as a journalist, a holiday decorator for restaurants and stores and a bartender. He loved working in bars and restaurants.

“When you’re a writer, you have to wait for the reviews to come out. When you work in a restaurant, you get the review immediately. It’s called a tip.”

He was very close to his siblings back in Kentucky who all had children, so Uncle Dick had a large extended family. Later when I became close to Jack Nichols, another Mattachine pioneer and a prolific writer who died in 2005, after becoming much more radical than most of his generation, Dick told me that having family made him less interested in leaving a legacy for history.

“I have lots of nieces and nephews,” he told me. “They will live after me.”

But history is unavoidable. We are now starting to see what huge courage and sacrifices these gay pioneers went through — Frank Kameny, who was jobless after a federal witchhunt deprived him of a position as an astronomer; Nick Nichols, whose own father, an FBI agent, plotted to have him murdered as a teenager; and Dick Leitsch, who took his role in it with such gallantry, never trying to reinvent history to try to concoct a place himself. He went from being America’s most famous, if only, homosexual, to almost forgotten.

In 2006, on the 40th anniversary of the Sip-In, he was asked by Scott Simon on National Public Radio: “Mr. Leitsch, is there still a Mattachine Society?”

He answered, “Oh, no, not after Stonewall. I kept saying, what’s the goal of Mattachine? And I always said the goal of Mattachine is to put ourselves out of business. When the cops walked into Stonewall, they tried to close it. People said, no, you’re not going to close our bar. We have a right to have our bars and it’s been established we have the right to have our bars. And Mattachine had nothing to do with Stonewall. That was something where the people rose up and did it. And that’s the beginning of the gay movement.”

Perry Brass has published 19 books, is the author of the bestseller “The Manly Art of Seduction, How to Meet, Talk to and Become Intimate with Anyone” and Ferro-Grumley Award-nominated “King of Angels,” a gay, Southern Jewish coming-of-age novel set in Savannah, Ga., in 1963. His newest book is “The Manly Pursuit of Desire and Love, Your Guide to Life, Happiness and Emotional and Sexual Fulfillment In a Closed-Down World.” “The Manly Art of Seduction” is now available as an audio book through Audible.com. Brass frequently writes for the Huffington Post and can be reached through www.perrybrass.com.