“I’m standing across the street from Stonewall in Sheridan Square. Here I was, an 18-year-old kid living at the YMCA in a $6-a-night room with no job, no prospects for the future, no real place to live and no money in my pocket. I’m thinking, What am I going to do? And it came to me: This is exactly what I want to do. I’m going to be a gay activist.”

More than 45 years after that fateful night outside the Stonewall Inn, Mark Segal still considers himself, first and foremost, an activist.

“That’s what’s inside me and what always will be,” he said. “Everything else is secondary.”

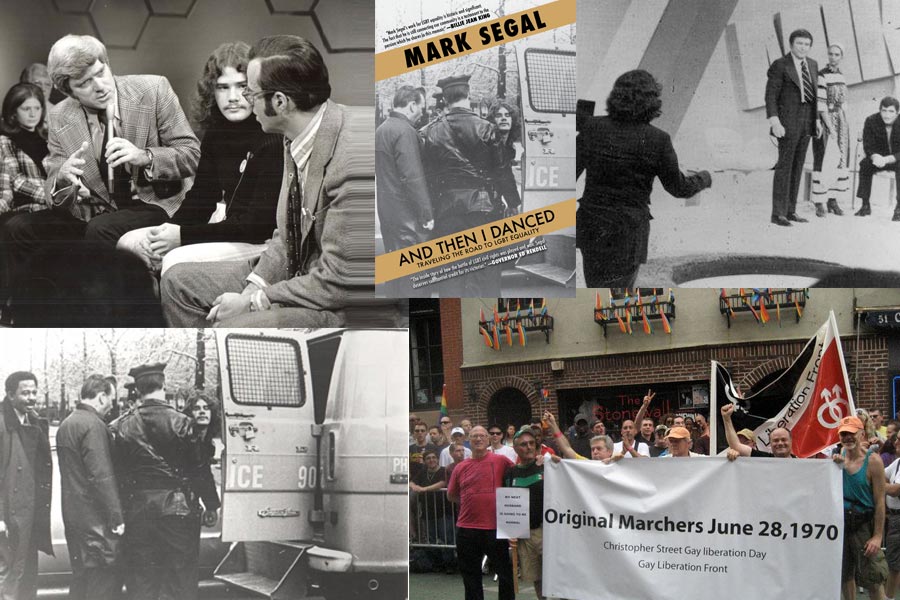

Adding to his list of “secondary” titles is a new one: “author.” Segal, the founder and publisher of Philadelphia Gay News, has just released his memoirs, “And Then I Danced.”

The 320-page book takes readers from Segal’s meager beginnings in a Philadelphia housing project to his pinnacle of dancing with his husband in the White House.

That was a journey that, Segal said, many have prompted him to write about over the years. But it wasn’t until a 2007 reunion of Gay Youth — which he founded in New York City in 1969 — that he started to gain an appreciation for his own role in the LGBT community’s development.

“We had the reunion in the New York Gay Community Center and there were about 100 of us who created this big circle. Each of us talked and, as they went around, people were saying that the organization saved their lives, that they were going to commit suicide until they found Gay Youth or that we saved them from bullying or harassment,” Segal said. “It wasn’t until I was halfway home on the train that it all of a sudden hit me what had just happened. Literally in the train car, I just started howling, just crying out loud. It really affected me.”

A few years later, another event again brought Segal full circle: Comcast senior executive vice president and chief diversity officer David L. Cohen invited him to join the media conglomerate’s Joint Diversity Council.

“I thought it was going to be just a rubber-stamp position and I said I didn’t have time for it. And David said, ‘Mark, there are only 40 people nationwide being asked to join this advisory board. Don’t you understand your history? There you were 40 years ago disrupting media, and now we’re asking you to advise media.’”

Cohen was referring to Segal’s infamous “zaps,” in which he targeted media personnel on air to raise awareness about LGBT issues.

That such encounters caught him by surprise, Segal said, is in part attributable to his tendency to stay forward-focused.

“I usually just go project to project to project and don’t look back,” he said. “So I really didn’t look back at all the things I had done or what the full impact of them was.”

But, as the significance of his decades of activism began to evince itself to him, Segal started seriously considering recounting that work in book form, especially at the prompting of his now-husband, Jason Villemez.

“Jason would say to me every night, ‘Do the book, do the book. Sit at your computer and start writing,’” Segal said, noting that at the time he was wrapping up work on one of the nation’s first LGBT-friendly affordable senior-living facilities, and Villemez knew the memoir-writing would be a good way to keep that momentum going. “He was conscious that the minute that ribbon was cut, I’d go from being 2,000 feet into the air to crashing to the ground if I didn’t have a project to work on,” Segal laughed.

Hiring an agent and publisher was easy work, he said. But, deciding what information to include and what to leave out was not.

Segal had been amassing vignettes of his recollections in the past few years, which he thought could serve as the memoir’s foundation.

“I thought I would just take what I had started writing and put it into book form. It didn’t quite happen like that; once I signed the contract, we basically threw out everything I had and went back to scratch,” he laughed.

He set to work creating an outline of his life, checking dates and facts and researching his own storied history.

That history began in 1951. Segal’s hardworking yet poverty-stricken parents, Shirley and Martin, raised him and his brother in a South Philadelphia housing project, after the city took over Martin’s bodega by eminent domain. As a member of the only Jewish family in the project, Segal’s feelings of being an outsider germinated from a young age, compounded by his worn clothes and lack of material possessions.

But what Segal didn’t lack as a child was conviction; in elementary school, he refused to sing “Onward, Christian Soldiers,” his first act of civil disobedience, which was supported by his mother. His grandmother, Fannie Weinstein, also played a pivotal role in his upbringing; she brought Segal, at age 13, to a civil-rights demonstration at Philadelphia City Hall, his first public demonstration — of many to come.

Exploring the struggles of his childhood in that first chapter, Segal said, was among the most challenging aspects of writing “And Then I Danced,” as the self-doubt he experienced in his youth resurfaced.

“The first chapter was extremely difficult to write because there are a lot of things in there that people don’t know about me. I struggled to continue with it because I really didn’t believe in myself,” he said. “I had Jason read the first chapter and at the end he was sitting on the sofa crying, and I said, ‘Wow, you really didn’t like it that much?’ And he said, ‘No, there were things here even I didn’t know.’ He really liked it and his support got me to continue.”

Working with editor Michael Dennehy, Segal crafted and re-crafted 15 chapters for a final product that takes readers through the national LGBT community’s evolution, seen alongside Segal’s own development.

From his burgeoning coming out — beginning with a childhood pull to the Sears Roebuck male models — Segal’s story is as much a commentary on the times as it is on his own experience.

“There was no name for it, at least none that I knew, but somehow it seemed wrong that I was looking at the men in the catalog,” he wrote.

Eventually, Segal learned the name for “it” and came out to his family, who, despite the wholly unaccepting societal nature of the time, embraced his identity. Segal’s own self-acceptance was intrinsically tied to New York City; he wrote that he realized at a young age that the city was a haven for gay people, so he moved to the Big Apple the moment he graduated high school.

He quickly became immersed in a growing and changing LGBT scene. The premiere LGBT activist group, Mattachine Society, was gradually becoming outdated, being ushered aside by a new wave of social revolution across the country.

And, a month after he moved to New York City, Segal found himself at Stonewall Inn on June 28, 1969. “And Then I Danced” takes readers through Segal’s first-hand account of the seminal riot and ensuing LGBT mobilization.

From those four reactionary nights came Gay Liberation Front, an organization that Segal said hasn’t gotten the credit it’s due.

“From the ashes of Stonewall came GLF, and GLF created the foundation of everything that today is the gay community,” Segal said. “We created the first trans organization in 1969. We created the first gay youth organization that dealt with gay issues in 1969. We created the first medical alerts for the gay community and the first gay community center. And at the end of that first year, we created the first gay Pride march. And all of it had to do with ending invisibility and creating community.”

It was with those missions in mind that, upon his return to Philadelphia in the 1970s, Segal undertook a campaign to target television coverage of LGBT issues, an undertaking that secured a wealth of television firsts — and forged his unlikely friendship with Walter Cronkite.

From the airwaves, Segal turned his attention to political circles, using his burgeoning notoriety to stage uniquely crafted demonstrations, such as chaining himself to a Christmas tree in Philadelphia City Hall and throwing a faux reception in the office of then-District Attorney Arlen Specter to thank him for his support for gay-rights legislation — which he had not yet offered.

Segal said it’s those kinds of actions that are needed to enliven the LGBT community’s modern political activism.

“We need that spark of creativity and fun again. Gay liberation can be fun,” he said. “We have to get away from the Internet and the online petitions and start doing things to get people’s attention. Our leaders are stuck in this quagmire because they’re used to being in suits and ties in offices in New York and Washington, D.C., and not out among people. We need to think outside the box. Be nonviolent, but think outside the box.”

Creativity needs to be paired with tenacity, Segal noted; another message he hopes readers, especially of the younger generation, take away from his book.

“I wanted to show young gay people how our community got the rights that we have today. It wasn’t writing letters or visiting Congresspeople. Many of us got arrested, received death threats, were targets of physical violence. It was a rough ride getting to where we are today. It wasn’t, ‘One, two, three. We’re there.’ Any social-justice movement takes a lot of work and a lot of time.”

For Segal, much of that work in the past four decades was focused on getting Philadelphia Gay News off the ground.

“And Then I Danced” traces the history of the publication, which celebrates its 40th anniversary next year, from its meager beginnings in a building with no plumbing and a leaky roof, where staffers would use quarters from the newspaper boxes for lunches, to a 2014 awards dinner where it received a national award for its investigative series on the murder of a local transgender woman.

Exploring such transitions through the writing process, Segal said, was eye-opening.

“I encourage anybody, whether you publish it or not, to write your own memoir. You learn so much about yourself,” he said. “It sounds strange, but I don’t think I had an appreciation for what I’ve accomplished until I read the finished book. This made me look back. I didn’t realize all the issues I was involved in, and how much change they had made over the years. I’m just beginning to get in touch with my own history. And I’m finding out I’m a different person than I thought I was.”