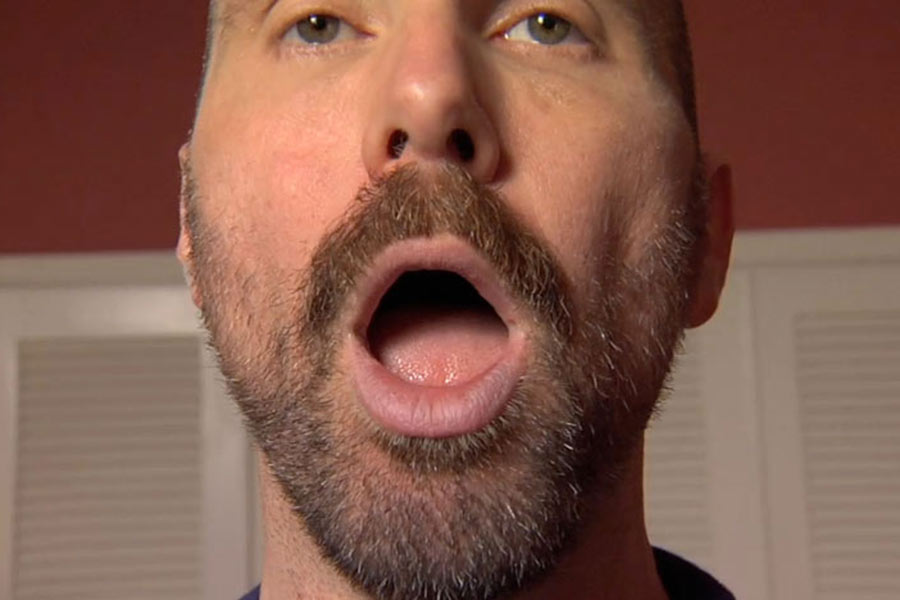

Filmmaker David Thorpe thinks he “sounds gay.” So he made a documentary, “Do I Sound Gay?” that chronicles him hiring speech and voice coaches to help him lose his sibilant S, gain confidence and get rid of his vocal effeminateness. His film, which opens July 17 at Ritz Theaters, nimbly chronicles this mission and features clips of Paul Lynde and “The Boys in the Band,” as well as interviews with Dan Savage and David Sedaris, among others, to address queer stereotypes, adjusting/covering, camp, “performing gayness” and even the advantages of sounding gay.

Thorpe recently talked via Skype with PGN about “Do I Sound Gay?”

PGN: You describe being “out of sync” with your voice and feeling a lack of confidence. Why do you — and so many other gay men (and women) — associate those feelings with sexuality?

DT: When I was growing up, I was made to feel that gay people were worthless. When I am vulnerable or insecure, it automatically connects to my sexual orientation — that part of my worthlessness comes from being gay. That’s what happens in the beginning of the film, and in my life. I’m single, middle-aged and unlovable: What’s wrong with me? One of the answers is, you’re a fag. I don’t rationally believe that, but when you grow up with that notion drilled into you for so many years, it’s a reflex.

PGN: Do you think your film breaks down or reinforces queer stereotypes?

DT: I hope it breaks down stereotypes. I have a straight guy who sounds gay and a gay guy who sounds straight. But it’s about embracing who you are and your femininity. It’s time to re-appropriate the feminine stereotype. I’m not the only person celebrating gay femininity, but I had to learn to re-embrace my own femininity.

PGN: Why do you think there is such shame associated with feminine-sounding men?

DT: I think men feel anxiety about feeling effeminate because we live in a sexist culture that devalues women and men who have feminine traits. We’re on the cusp of change, but it will take a couple more generations for widespread change.

PGN: You emphasize and even embrace the visibility of gay icons like Paul Lynde and Liberace, but also seem to be rejecting this kind of behavior in your own life. Isn’t that talking out of both sides of your mouth?

DT: That’s the journey of the film. When I began the project, I was keenly aware of not wanting to be flamboyant anymore, because I felt it was a reason why I was alone and unhappy. I wanted to be really honest about those feelings. I’m not the only one who has them. I was out for 20 years and an AIDS activist, and I was still not comfortable with it. Maybe I needed to be a different kind of person? At the same time, I didn’t think that I could learn to accept myself in middle age. I felt like I was cooked. It was just as valid a path to change, the way gay men go to the gym or dress to be more masculine. I didn’t think there was anything wrong with shaping my voice. I knew that that was coming from a place of shame. I went down both paths simultaneously, but it was answering all the questions about why people sound gay and hearing others’ stories, and looking at our culture. I found a path I didn’t know was out there for me.

PGN: How did you respond, growing up, to kids who were effeminate-sounding?

DT: When I was growing up, I wanted to reach out to feminine boys, but I stayed far away because I knew that effeminacy was “catching,” and the safest thing to do was not hang around effeminate boys, and boys who sounded gay.

PGN: You are told in the film that you started sounding “more gay” after you came out. Did you recognize an increase in that behavior around that time as well?

DT: I think that everything about me got gayer. But I think my voice was probably what changed most, and certainly my friends noticed it. When voices sound gayer, it rankles people. The voice is an essential part of who someone is. When it’s changed, people wonder why.

PGN: You hired speech pathologists and voice coaches to change your voice. Did you feel that was a good investment?

DT: It was a great investment at the time, because it helped me get in touch with my voice, and sound more authentically myself, but I don’t need to do it anymore. When I’m relaxed now, my larynx settles into vocal home base, and I hang out in that place, which gives me the most ease. If you are uncomfortable with your voice, you should find out why that is, and find out how to use the one you have.