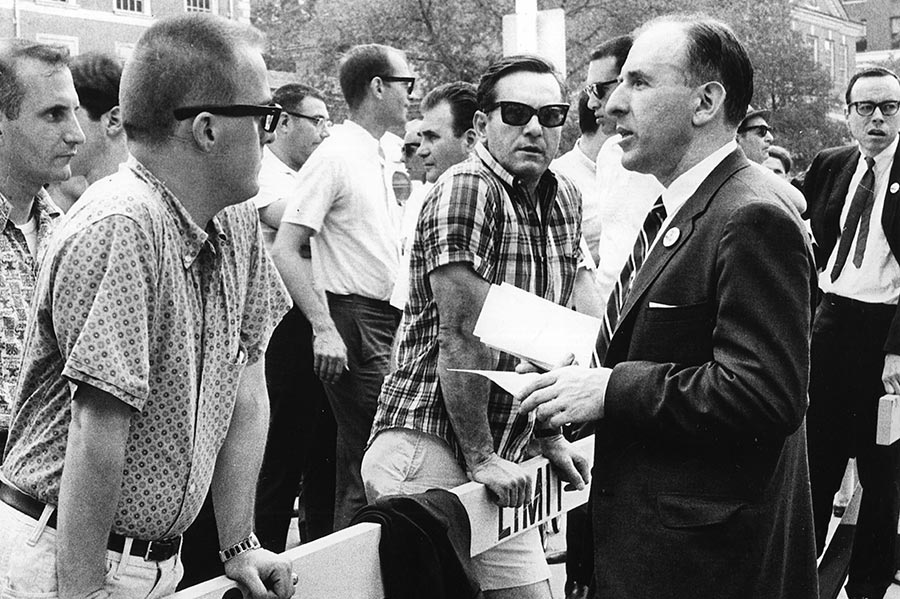

They came on buses from Washington, D.C., and New York City. They dressed in suits and ties and dresses. They readied cardboard signs that carried messages whose simplicity underscored the journey that lay ahead of them: “Homosexuals should be judged as individuals,” “Gay is good” and “Equal opportunity for all.”

And at 1 p.m. July 4, 1965, the 40 protesters — 33 men and seven women — set off outside Independence Hall, on Chestnut between Fifth and Sixth streets. On a day in which Americans were celebrating freedom and equality, they marched in a line outside the national symbol for two hours, calling for basic freedom and equality for gay and lesbian citizens.

The effort became known as the Annual Reminder Day marches, a tradition that continued on Independence Day through 1969 — preceding the Stonewall Riots in New York City, often thought of as the birthplace of the modern LGBT-rights movement, by four years.

The tone of the marches, however, was wholly different than that of the famous Stonewall uprising.

Conceived by activist Craig Rodwell, the event was largely spearheaded by Mattachine Society’s Frank Kameny, based in Washington, D.C., and Philadelphia activist Barbara Gittings of Daughters of Bilitis.

Kameny, who died in 2011, told PGN the previous year that the date and location were both selected for their symbolism and inspired, in part, by previous demonstrations earlier that year at the White House and other government buildings in Washington, D.C.

“We thought that Fourth of July just seemed conceptually appropriate and there would be no better place to do them than in front of Independence Hall,” he said.

The marchers were all kept to strict dress and behavioral codes: They were expected to present dressed according to gender expectations of the time, and march without rowdiness, including hand-holding or other signs of affection.

The intent of that style of protest was to demonstrate that gay and lesbian people were no different than heterosexuals, marcher Randy Wicker told PGN in 2010 — itself a bold notion.

“It was considered extremely radical just to be out there looking like corporate nonentities, in suits and ties and dresses, representing the masses of gay people that at that time were totally invisible,” Wicker said.

Many of the marchers who participated in the 1965 demonstration came from New York City and D.C., a testament to the notion that many locals were hesitant to take such a public step in their own city.

The march proceeded with little fanfare and no run-ins with police. William Way LGBT Community Center archivist Bob Skiba noted that the police had recently formed a squad to specifically oversee civil-disobedience actions, which were catching steam in the mid-1960s.

“They had just formed this squad to deal with people protesting, chaining themselves to things,” Skiba said. “Barbara and Frank got a permit and when they went back to renew it after that first year, the police chief thanked them for being so well-behaved and said there were no problems at all with the march.”

The number of participants ebbed and flowed throughout its five years: 50 in 1966, 30 in 1967, 75 in 1968 and 150 in 1969, which took place one week after Stonewall.

After that time, Annual Reminder organizers discontinued the Philadelphia demonstration and refocused their efforts on the Christopher Street Liberation Day in New York City, to mark the one-year anniversary of Stonewall.