History Highlight

As the 50th anniversary of the Annual Reminder Days approaches, PGN will explore events, ideas and people who had an impact on local and national LGBT history.

Little Pete’s, at 219 S. 17th St., may soon be history as plans swirl for its possible demolition to make room for a high-rise hotel. But history was already made at that location, where a diner that previously occupied the space served as the setting for one of the nation’s earliest LGBT-rights demonstrations.

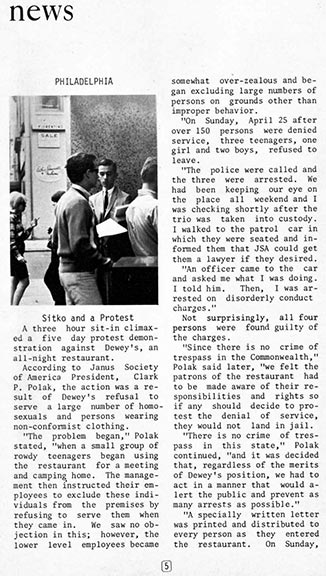

On April 25, 1965, four people were arrested after a sit-in at Dewey’s Famous, a fast-food chain with eateries around the area, whose 17th Street locale had been denying service to diners who did not comport with gender norms. Fifty years later, the protest is being remembered for the volumes it spoke about 1960s culture — and for securing a win for the LGBT community.

“It was highly successful,” Bob Skiba, archivist at William Way LGBT Community Center, said about the historic event. Skiba noted that local LGBT leaders are planning to submit the former Dewey’s location to the National Park Service for its consideration for a new program highlighting LGBT historic spots.

According to archival material documenting the events, the sit-in was prompted after the management at the 17th Street Dewey’s — which also had an LGBT-centric location near 13th and Locust streets — instructed its employees to refuse to serve a group of rowdy, and presumably LGBT, teens who frequented the restaurant.

But the staff took that order further and started denying service to diners whose appearances did not conform to gender norms, which led to about 150 people amassing at the diner April 25 in protest. All were turned away but three teens — two boys and a girl — who refused to leave and were arrested on disorderly conduct charges. Clark Polak, then the head of LGBT-rights group Janus Society of America, headed to the scene and also was arrested.

“I walked to the patrol car in which they were seated and informed them that JSA could get them a lawyer if they desired,” Polak recounted in an article in Drum, a magazine published by Janus Society. “An officer came to the car and asked me what I was doing. I told him. Then, I was arrested on disorderly conduct charges.”

In the days that followed, Janus Society conducted a leaflet campaign outside Dewey’s.

“Since there is no crime of trespass in the commonwealth, we felt the patrons of the restaurant had to be made aware of their responsibilities and rights so if any should decide to protest the denial of service, they would not land in jail,” Polak explained.

On May 2, another group was denied service and refused to leave — a sit-in that ended peacefully, with no arrests. In fact, according to the Drum piece, the police were almost apologetic.

“It was a far cry from the previous Sunday and I was quite politely told that we could stay in there as long as we wanted as the police had no authority to ask us to leave,” Polak recalled.

“Things calmed down after that,” Skiba said. “I can’t find any other references to discrimination there after that. And Janus looked at it as a big win.”

Apart from educating the restaurant and patrons at the time, the sit-in also demonstrated, for future generations, the climate of the time, Skiba said.

“The concept of a sit-in was really tied to the 1960s black civil-rights protests that were going on and with the era of civil disobedience,” he said. “Dewey’s kind of happened like early demonstrations out in California, the Compton cafeteria sit-ins; it was spontaneous. But then the Janus Society stepped in and leafleted and it became a peaceful sit-in rather than a riot.”

Skiba noted that just a year or two before the events, the city formed a civil-disobedience squad within the police department because such actions were happening so frequently.

“There were so many demonstrations around the city, for racial equality and against the Vietnam War,” he said. “So this could be one reason this was handled so well by the police that second weekend.”

Marc Stein, author of “City of Sisterly and Brotherly Loves: Lesbian and Gay Philadelphia, 1945-72” and “Rethinking the Gay and Lesbian Movement: Historical Perspective,” noted that Dewey’s also signified a deviation from some other LGBT-rights demonstrations of the time.

This summer, Philadelphia will host a large-scale celebration of the Annual Reminder Days, an organized picket calling for gay rights that was held outside Independence Hall each year on July 4, from 1965-69.

At those actions, participants were required to conform to gender standards: dresses for women and suits and ties for men.

“Frank Kameny was one of the lead organizers of what became the Annual Reminders, and his rules for the picketers weren’t completely at odds with what happened in other social movements in the ’50s and early ’60s about how activists were supposed to comport themselves,” Stein said. “Kameny insisted on an older conception of what a nonviolent protest should look like, and it’s understandable that the homophile movement wanted to counter stereotypes about gays and lesbians. But, that did mean, of course, excluding people who were gender-crossers in one way or another because they didn’t want to challenge the concept of gender.”

That was not the case at Dewey’s.

Although the three teens who led the Dewey’s sit-ins have never been publicly identified, Stein said it’s likely that some of the people involved with the demonstrations might identify as transgender by today’s definitions.

“Janus made it clear that the people they were defending were violating conventional gender norms. This isn’t an era yet where they were talking about ‘transgender’ or ‘transsexual’ commonly, but it seems clear to me that at least some of these people were what we consider trans today,” Stein said. “And the group may have included drag queens, butch lesbians, cross-dressers and a whole variety of other people who were one way or another seen as nonconformist.”

Stein noted that, while the Annual Reminders deserve a place in LGBT history books, so too does Dewey’s.

“The Annual Reminders were significant protests and they did get more attention at the time than Dewey’s did, within the homophile movement as well as the mainstream. They were strategically effective in selecting Independence Hall and using patriotic language to get their message across. It was a breakthrough demonstration for the homophile movement,” he said. “But I think we’re focusing a lot on the Annual Reminders and not Dewey’s because of the same reasons that existed back then: The Annual Reminders fit in more with mainstream ideas about American values and gender norms while Dewey’s was more confrontational. And Dewey’s addressed the rights of more transgressive members of the LGBT community, and I think there’s still elements of marginalization and anxiety associated with those members of our community.”

While the Stonewall riots of 1969 are often thought of as the birth of the modern LGBT-rights movement, Stein noted that both the Annual Reminders and the Dewey’s sit-ins illustrate the lengthy and ever-evolving history of the fight for LGBT rights.

“The movement clearly mobilized and radicalized to an unprecedented degree after Stonewall in 1969, and I think the Annual Reminders and Dewey’s show us there was a much longer tradition of political organizing and political protests that really stretch back to the founding of the Mattachine Society in the early ’50s,” he said.

“But the Annual Reminders and Dewey’s signal that the movement was transitioning in the mid-’60s. Too many historians and journalists have been wrong to present the homophile movement as conservative, accommodationist and ineffective throughout the 1950s and ’60s. That transition and radicalization in the mid-’60s shows us that the movement has long been divided; we’ve long had diverse politics. And Dewey’s reminds us to recognize that there was a part of the movement before Stonewall that was committed to addressing gender diversity, as well as sexual diversity.”