A 25th-anniversary edition of Lesléa Newman’s children’s book “Heather Has Two Mommies,” with brand-new illustrations and updated text, has given the classic new life for families today. And Newman is amazed that some of the children who read “Heather” when it first came out could now be reading it to their own children, she told me in an interview.

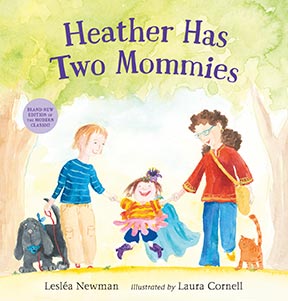

The most obvious changes in the new edition is the addition of full-color, contemporary illustrations by Laura Cornell that replace the originals of Diana Souza. Newman said she loves how the new pictures enhance the text, showing that “Heather’s mothers adore her.” For example, she said, it’s obvious Heather alone picked out her mismatched first-day-of-school outfit, and “that says to me her parents are really allowing her to be herself.” Heather also “looks really confident” going into her classroom on the first day of school, “and I think that reflects good parenting.”

Heather’s moms now also, subtly, sport matching rings. To my mind, however, the easy-to-miss rings will have less impact on young readers than will the shift in Heather’s attitude. The original text had her start to cry when she thinks about whether she is the only child at school without a daddy. That always made me hesitate to share “Heather” with my son — I feared it would give him the idea that not having a daddy was something to cry about. In the revised story, however, Heather merely wonders if she’s the only one without a daddy — without crying — before the teacher takes the whole class on a joyous exploration of their many-structured, many-race families.

Newman explained the change as part of her becoming ”more subtle and nuanced” as a writer. Heather’s wondering “is much more open to interpretation on the part of the reader,” who “can insert him or herself into the story and have his or her own reaction along with Heather.” It also reflects, to my mind, a climate of growing acceptance, when having a different family structure may be less likely to cause tears.

To understand how far “Heather” has come, it helps to look at her origins. “Heather” was not, in fact, the first picture book to show same-sex parents. That was Jane Severance’s 1979 “When Megan Went Away,” about a girl dealing with her mother’s partner moving out. However, “Heather” took off in a way Severance’s book didn’t — perhaps because it showed a happy, intact two-mom family.

Newman got the idea for “Heather” when a lesbian mother stopped her on the street and asked for a book that reflected her family. After more than 50 publishers refused to take it, Newman and her friend Tzivia Gover, a lesbian mom with a desktop publishing company, decided to try it themselves. They gathered contributions $10 at a time — “before Kickstarter, actually licking envelopes” — and co-published “Heather” in 1989.

“I really wasn’t thinking much past my local community, let alone the national or international community at that point,” Newman said.

The next year, LGBT publisher Alyson Publications bought the rights to “Heather” when it launched a line of children’s books.

For several years, letters trickled in to Newman from both lesbian and straight parents saying how much their children liked “Heather.” Then, in 1992, controversy erupted. Copies of “Heather” and another Alyson picture book, “Daddy’s Roommate,” were used as examples of “the militant homosexual agenda” by an Oregon group campaigning to allow antigay discrimination. In New York City, both books were part of a proposed “Rainbow Curriculum” of suggested books to teach respect for all types of families, but were removed in the face of opposition.

Around the country, “Heather” faced challenges in schools and public libraries from those who wanted it removed or restricted, and earned a top-10 spot on the American Library Association’s Most Frequently Challenged Books list for 1990-99. Most librarians supported it, though, Newman noted, and it largely stayed on shelves.

Slowly, change happened, both in society and in the publishing industry. In 2008, two decades after scrounging for money to publish “Heather,” she was asked by an editor at Tricycle Press to write two board books about same-sex-headed families. Newman marveled, ”I was actually being asked to write these books for kids younger than the ‘Heather’ set, and being paid to do so.” Tricycle published them as “Mommy, Mama and Me” and “Daddy, Papa and Me,” along with her picture book “Donovan’s Big Day,” about a boy on his moms’ wedding day. Tricycle was since bought by industry giant Random House, which still publishes all three books.

“That’s a big shift,” Newman said.

Now, the 25th-anniversary edition of “Heather” is being published by Candlewick Press, an independent publisher of mainstream children’s classics like Sam McBratney’s “Guess How Much I Love You.”

Despite this progress, however, Newman noted there are still only a handful of LGBT-inclusive picture books each year. One reason, she said, is that color art makes picture books expensive to produce, and publishers may fear that only the type of family featured in a book will buy it — which Newman does not think is true.

In contrast, she says her own book is not only for kids with two moms “but for kids who have friends who have two moms, for kids who have classmates who have two moms or kids who don’t even know other kids who have two moms, just so that they are aware that families come in all different variations.”

While Newman believes “we still have a lot more work to do,” she added, “I hope my humble little book is helping educate kids to appreciate, respect and celebrate difference.”