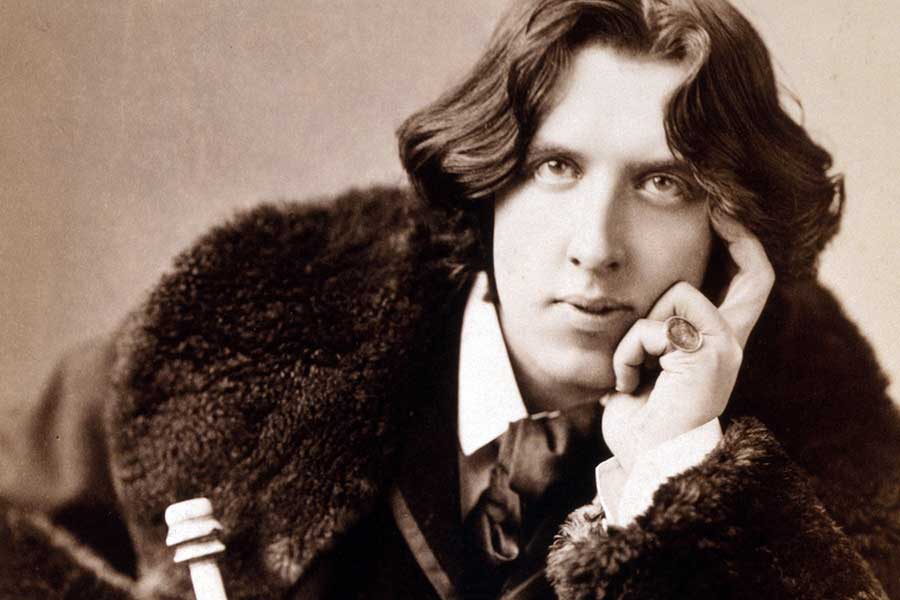

Oscar Wilde’s presence looms large over Philadelphia’s cultural landscape this winter. And just like Wilde did when he visited the city in 1882, he is sure to amuse, inspire and even scandalize.

The East Coast premiere of “Oscar,” an opera about Wilde’s tragic final years, is the highlight of all this activity. The show opens at the Academy of Music Feb. 6 and runs for five performances.

David Daniels, the famous countertenor, stars as the Irish-born author and gay icon, whose world collapses when a misguided lawsuit backfires and he is sentenced to two years of hard labor for what the Victorians referred to as “gross indecency” with men.

Daniels’ portrayal of the brilliant but doomed writer was first seen in Santa Fe in August 2013. According to James Oestreich of The New York Times, the countertenor “was superb, not only singing but also acting the role with a savvy Wildean mix of arrogance and vulnerability.”

“Oscar,” a coproduction of Opera Philadelphia and The Santa Fe Opera, features music by Theodore Morrison and a libretto by Morrison and John Cox, a notable English opera director. Singers William Burden, Dwayne Croft and Heidi Stober round out the cast.

In addition to “Oscar,” numerous events examining Wilde’s life and work are taking place throughout the region. They include the Jan. 26 recital “A Taste of Opera: Wilde and Whitman in Song,” at the Free Library of Philadelphia, and the Jan. 28 screening of “The Picture of Dorian Gray” at the Bryn Mawr Film Institute.

Of special interest to the LGBT community is Chris Bartlett’s Feb. 3 Q&A with Daniels. Bartlett, executive director of the William Way LGBT Community Center, is also a longtime opera fan and said he’s excited about the upcoming premier.

“Hearing a countertenor is such a magical, special thing,” he said. “It’s a rare and, dare I say, queer sound.”

Death (Luplau) visits Oscar and his fellow inmates at Reading Gaol.

William Way is also cosponsoring Out at the Opera on Feb. 13. LGBT opera lovers can come out en masse to enjoy Oscar and show their gay pride. The evening begins with a pre-performance talk by Reggie Shuford, executive director of the ACLU of Pennsylvania. Shuford will discuss legal issues confronting the LGBT community, both in Wilde’s day and now. A $20 discount on tickets is available (www.operaphila.org/out-opera).

If this flurry of interest in Wilde seems out of place, it is important to note that Philadelphia can lay claim to playing a role in Wilde’s life. Although he spent most of his adult life in London, the famous wit visited Philadelphia twice during his 1882 tour of America. While here, he delivered two public lectures and gave numerous interviews. The visit also eventually led to an acquaintance with Philadelphia publisher J. M. Stoddart, who commissioned Wilde’s only novel, “The Picture of Dorian Gray.”

More importantly, on both occasions, the flamboyant young aesthete traveled to Camden to visit Walt Whitman, whom he admired tremendously. This meeting was undoubtedly significant to Wilde. Whitman recorded his impressions of the visit in a letter to his young friend Harry Stafford, describing Wilde as “a fine large handsome youngster.” Moreover, the rustic bard added, Wilde “had the good sense to take a great fancy to me.”

Wilde was only 27 when he met Whitman. He had not yet written his delightful farces or penetrating critical essays. Nor had he met the young man he loved, Lord Alfred Douglas, known as Bosie.

Bosie (Reed Luplau) haunts Oscar’s memory throughout the opera

That relationship changed the course of Wilde’s life and it’s his final years that are the focus of “Oscar.” For Daniels, who portrays the LGBT icon, it’s important for audiences to understand the opera’s context: It is not a trifling farce or drawing-room comedy.

“Our story is about the horrible way he was treated in the last few years of his life, the imprisonment, the way Bosie treated him,” the actor said.

Nor is it a romance. As Daniels noted, Wilde’s relationship with Bosie was complicated at best.

“Yes, we’ve all been in relationships where there’s a lot of love but there’s a lot of ugliness as well.”

It’s an important story, because Wilde’s personal travails throw into glaring view both how far LGBT people have come in the last 125 years and how far they still have to go.

The story of how “Oscar” came to be is interesting in itself. Almost a decade ago, Daniels recounted, he was performing a recital at London’s Barbican, singing compositions by Theodore Morrison. Distinguished director John Cox was in the audience and came backstage afterwards to congratulate them.

According to Daniels, “John Cox loved the music and met Theo backstage and said, ‘I love your music. Have you ever thought of writing an opera?’ And Theo said, ‘No, I haven’t, but now I will!’ And that’s how it really happened.”

Fortunately for Daniels, the role was created with him in mind. It highlights his distinctive countertenor voice and makes him the dramatic focus of the opera.

“It’s a unique situation and position to be in for me because, no, operas are not written for specific singers every day,” he acknowledged.

That “Oscar” covers a difficult, even brutal period in Wilde’s life was not lost on Daniels. He admitted that preparing for the opera’s initial staging in Santa Fe was emotionally draining. As a seasoned performer, this came as a bit of a surprise.

Wilde (Daniels) at Reading Gaol

“I’m not one to lose it,” Daniels said. “And I lost it in rehearsals, over and over again. And it was so powerful to all of us, sitting around with tears in our eyes, creating this the first time. That surprised me. I didn’t think that that would be the case.”

Those challenges are more than made up for by the wonderful opportunity “Oscar” presents the singer, both personally and professionally. Daniels, who is openly gay and is married to his partner, finally has the chance to play a gay man on stage.

“I’m used to playing roles where I’m in love with a woman,” he said. “I’m playing Caesar; I’m in love with Cleopatra. I’m Nero; I’m in love with Poppaea. Romeo; in love with Juliet. I’ve never been able, as a gay man, to play a gay man on stage. And that’s just been overwhelming.”

It’s precisely those issues that Bartlett hopes to explore with Daniels at their public discussion Feb. 3. Bartlett said he’d like the conversation to include a mix of general reflections on LGBT life in the arts and personal anecdotes from Daniels’ life as a gay opera singer.

“I’m curious to talk to him about some of the history of participation of LGBT people — and particularly gay men — in opera as fans, as composers, as performers, and to what extent he feels that his sexual orientation and gender identity impacted his love for opera, his decision to get involved in opera and his success.”

Bartlett noted that “Oscar” fits in nicely with upcoming offerings planned for Reminder 2015, a series of events celebrating LGBT history.

“It’s thrilling that there happens to be an opera dealing with issues of gay history and one of our greatest gay figures,” he said.

For more information, visit www.operaphila.org.

Delaware museum explores Wilde play in art

“Oscar Wilde’s Salomé: Illustrating Death and Desire,” which opens Feb. 7 at the Delaware Art Museum in Wilmington, focuses on the way this scandalous 1892 play has inspired visual artists.

Among the roughly 35 pieces on display are lithographs by Aubrey Beardsley, who illustrated the first edition of “Salomé” in 1894, and engravings by Barry Moser, whose images accompany Joseph Donohue’s celebrated 2011 translation, which rendered the original text’s florid French into frank, idiomatic English. Other pieces being shown first appeared in periodicals and books.

“Salomé” is darker than the amusing comedies for which Wilde is justly admired. His sources for this retelling of John the Baptist’s beheading, found in the Gospels of Matthew and Mark, are brief, spare accounts of the conflict between worldly power and divine authority. Immorality undoubtedly forms the backdrop, but Wilde injected erotic and macabre elements into the story, transforming it into a perverse tale of decadence and transgression.

Preparations for staging “Salomé” with the famous actor Sarah Bernhardt were underway in London when the Lord Chamberlain prohibited it. In a sense, the public didn’t get to “see” Wilde’s shocking play until an 1894 edition featuring Beardsley’s striking pen and ink line drawings was published.

The artist’s sensual, suggestive drawings, transformed into lithographs, have had a lasting influence on how later artists have approached the text.

“Beardsley’s illustrations in themselves greatly influenced the reception of the drama, much more so than if there had been no accompanying illustrations,” said Margaretta Frederick, the exhibit’s curator.

The Beardsley portfolio is part of the Delaware Art Museum’s permanent collection. It includes several images that never appeared in the 1894 edition of “Salomé,” as well as some that are now shown with sexual imagery unaltered.

The work of other artists inspired by the play, including Louis Jou and Valenti Angelo, is also on display. Fredrick confesses a particular fondness for French painter Andre Derain’s pictures of Salome’s” dance.

“What I really like is that his balletic imagery echoes Wilde’s rhythmic prose,” she said.

But the other major presence in this exhibit is the work of Moser, a contemporary artist. His dark, moody depictions of the story stand in stark contrast to Beardsley’s delicate-looking but decadent drawings.

According to Frederick, “Moser’s contributions for this 21st-century interpretation freely convey the decadence of Wilde’s characters with a frank forthrightness that closely mimics Donohue’s translation.”

For more information visit www.delart.org.

Rosenbach brings Wilde back to Philly

“Everything is Going on Brilliantly: Oscar Wilde and Philadelphia,” a new exhibit at the Rosenbach of the Free Library of Philadelphia, makes the case that the City of Brotherly Love has had an enduring place in the Irish-born author’s life and art.

The exhibit, which opens Jan. 23, contains roughly 50 objects, some related to the famous wit’s two visits to the city, others accumulated over the years by collectors and scholars.

The curators, Dr. Margaret Stetz and Mark Samuels Lasner of the University of Delaware, drew on decades of experience studying Wilde to create this exhibit. In addition to displaying items from the Rosenbach’s collection, they’ve pulled together material from numerous archives, including the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas.

People visiting the Rosenbach, located at 2008-2010 Delancey Place, will find themselves transported back in time by the photos, advertisements and manuscripts documenting Wilde’s impact. Even the rooms have been designed to frame the experience.

“We want visitors to the exhibition to feel as though they are entering Wilde’s world — or, at least, the sort of rooms where artistically minded Philadelphians might have met Wilde in 1882, during his two visits to the city,” Stetz said.

The most interesting pieces on display — perhaps shown publicly for the first time — were discovered right here in the Free Library of Philadelphia: a hand-corrected typescript of the play “Salomé” and a notebook from around 1880 containing unrecorded versions of early poems and sketches.

Stetz is particularly fond of the notebook.

“It’s not only of immense scholarly importance, but it’s a lot of fun to look at, because it’s filled with Wilde’s doodles — many of them of heads,” she said. “Clearly, a decade before he wrote “The Picture of Dorian Gray,” Wilde was already obsessed with portraits, and he loved sketching faces, whether real or imaginary”

Wilde visited Philadelphia twice during his 1882 lecture tour of America. In addition to delivering public talks, he gave numerous interviews and met with his cousin, Father Basil Maturin, the rector of St. Clement’s Church.

Both times, the flamboyant aesthete crossed the Delaware to visit the rustic bard Walt Whitman, whom he admired. A letter from Whitman to Harry Stafford describing their meeting is on loan from the Library of Congress.

On Feb. 5, Stetz and Samuels Lasner will lecture at Rosenbach on various aspects of Wilde’s Philadelphia connections.

For more information, visit www.rosenbach.org.