The Philadelphia of 2015 is a very different place than the Philadelphia of 2008.

Same-sex marriages have been legally celebrated at our City Hall; we have a sea of pioneering laws that both protect and empower LGBT citizens; agencies from the police department to youth- and senior-serving organizations have opened their doors, and minds, to LGBT inclusion; and our community plays an active, valued and visible role in the everyday operation of our city.

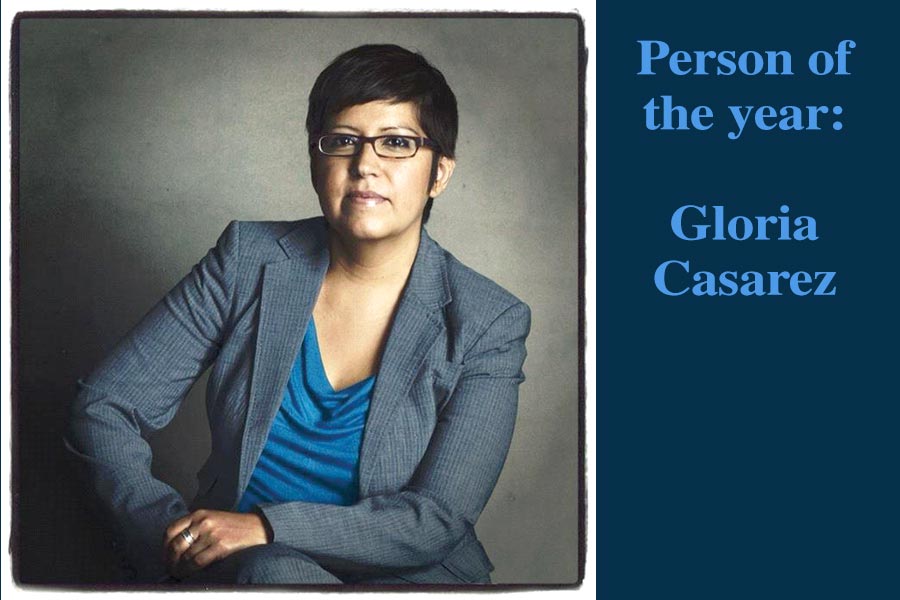

There are innumerable people and entities who have played a part in Philadelphia’s LGBT progress in the past few years, but none more central and significant than Gloria Casarez. From her appointment as the first director of Philadelphia’s Office of LGBT Affairs in July 2008, up until her death Oct. 19, 2014, Casarez worked each day to improve Philadelphia for LGBT, and all, people. From advocating for pro-LGBT bills to raising awareness about LGBT issues — from the corridors of City Hall to the corridors of city schools — to building relationships and inroads among our community and city leaders, Casarez’s legacy is just beginning to come to fruition.

For her decades of unyielding, inspiring, impactful leadership, which will continue to shape our community into the future, PGN names Gloria Casarez our 2014 Person of the Year.

LEGISLATION

A cornerstone of Casarez’s tenure was her advocacy — both publicly and behind closed doors — for a number of pro-LGBT pieces of legislation. Among the laws that City Council passed in the last few years were four that advanced LGBT equality, and Casarez played a key role in each, helping to draft language, consult on contextual issues and lobby for their passage:

Fair Practices Ordinance overhaul, 2011

Introduced by City Councilman Bill Greenlee, the measure overhauled the Fair Practices Ordinance, the city’s LGBT-inclusive nondiscrimination law, instating uniform language to make the law compliant within itself, as well as with other state and federal laws. The measure increased the fine associated with violating the law to $2,000, the maximum allowed by state law, and facilitated the process for life-partner registration, lessening the number of months the couple needed to be together from six to three, and the number of documents for verification from three to two. It was approved unanimously by Council, and Mayor Nutter signed it into law March 17.

Equal Benefits Bill, 2011

Introduced by Councilwoman Blondell Reynolds Brown, it mandated that city contractors receiving more than $250,000 from the city must extend the same benefits they offer heterosexual married partners of employees to same-sex partners of employees. In planning for the measure, Reynolds Brown’s first phone call was to Casarez, who remained involved from beginning to end, meeting with stakeholders, testifying at a legislative hearing before Council unanimously passed the measure and ultimately speaking at the Dec. 12 bill-signing.

LGBT Equality Bill, 2013

Introduced by Councilman Jim Kenney, the bill revamped the city’s health-care plan to ban discrimination against non-union transgender city employees and instated first-in-the-nation tax credits for companies that provide trans-specific health-care coverage and domestic-partner benefits. The legislation was approved in a 14-3 vote and signed into law by Nutter May 7. A Kenney spokesperson said the legislation “would not have happened” without Casarez, who championed it within the administration.

LGBT Hate Crimes Measure, 2014

Introduced by Kenney and Reynolds Brown shortly after a same-sex couple was attacked in Center City, the legislation instated fines of up to $2,000 and up to 90 days imprisonment for crimes motivated by a victim’s sexual orientation, gender identity or disability, classes not yet protected under the state’s hate-crimes law. Council unanimously approved the measure shortly after Casarez’s passing, and Nutter signed it the following month.

EDUCATION

Casarez worked to educate a diverse number of audiences on LGBT issues — policymakers, city and state employees, social-service providers, educators — using both formal and informal means:

Speaking out

Casarez provided official testimony before a number of bodies on LGBT issues.

In 2008, shortly after her appointment, Casarez testified before a state Senate committee on behalf of Nutter regarding legislation that sought to instate a constitutional ban on same-sex marriage in Pennsylvania.

In her remarks, she referenced the negative impact the measure would have on economic development and tourism.

“Ultimately, there’s no positive impact bills like this can have on the economy of cities like Philadelphia,” she testified.

Casarez sat on the LGBTQ advisory committee of the Philadelphia School District, a group tasked with heightening awareness and cultural competency throughout the district on LGBT issues. In 2009 she personally brought the group’s recommendations — which included LGBT training for principals, a district letter to constituents affirming LGBT families and other items — to then-schools chief Arlene Ackerman. The following year, she testified at a Philadelphia Commission on Human Relations hearing on intergroup violence about LGBT-specific concerns, blasting Ackerman and the district for their “many missed opportunities” by failing to implement the recommendations.

Training

Casarez sat on the Police LGBT Liaison Committee and was among a group of members who regularly participated in LGBT sensitivity training for police cadets. She spoke from a city perspective, reviewing policies and programs relating to the LGBT community and offering herself and her office as a resource.

She was the driving force behind the 2009 LGBT resource guide for city schools. The materials provided practical information for school officials, teachers and counselors, including lists of local LGBT organizations and resources for youth, as well as tangible steps schools could take to stem bullying and harassment and create more inclusive and affirming environments for all students.

Advising, representing mayor

Casarez worked directly for Nutter and, as such, advised him on the full gamut of LGBT issues. She often wrote speeches for the mayor and accompanied him to community events, briefing him on community goings-on and concerns.

She also represented the mayor to both LGBT and non-LGBT audiences, from the Philadelphia Bar Association in 2008 to a panel of international journalists in 2012.

Nutter was a founding member of the Mayors for the Freedom to Marry, and later co-chaired the national initiative. At a City Hall celebration the day Pennsylvania legalized same-sex marriage, Casarez read remarks by the mayor, who was out of town. That weekend, Nutter officiated same-sex weddings at City Hall.

Informal awareness

As often as Casarez formally educated audiences on LGBT communities, she may have just as frequently been informally raising awareness.

Casarez personally visited the city clerk’s office when there was confusion over the domestic-partner registry, explaining the specifics of the law to staffers. When a city employee ran into trouble adding a same-sex partner to the city’s health plan, Casarez intervened. In her remarks to the PCHR in 2010 on intergroup violence, she noted that she fielded calls all the time from the families of LGBT students being bullied and contacted school officials on their behalf.

BRIDGING GAPS

Casarez was tasked with, and succeeded at, bridging gaps between the LGBT community and city government — inviting the community into city operations and enhancing the city’s role in the community.

Community visibility, inclusion

One of Casarez’s trademark accomplishments marked its fifth anniversary just weeks before her death — and was both a symbolic invitation to the community and an affirmation of the city’s support.

In 2010, she spearheaded the rainbow flag being flown for the first time outside of Philadelphia City Hall, to mark LGBT History Month. Each year, she organized the flag-raising ceremony, during which LGBT community organizations and leaders were honored. The day Pennsylvania legalized marriage equality, the city quickly raised the rainbow flag and, the day after Casarez’s passing, the flag, already up for History Month, was lowered to half-staff.

Within three months of taking on the position, Casarez established the Mayor’s Advisory Board on LGBT Affairs, comprised of a diverse group of leaders, who explored issues affecting the local LGBT community and made recommendations to the mayor. The next year, she helped create a committee that worked to inform local LGBTs about the need for their participation in the U.S. Census. She later helped bring together community organizations for a groundbreaking study on LGBT seniors.

Heightened city presence

Less than three weeks before she passed, Casarez delivered the keynote address for the LGBT History Month celebration of PECO’s LGBT employee group — mirroring myriad similar undertakings throughout her six years as the LGBT director.

From annual events like Philadelphia Dyke March and Philadelphia Pride to impromptu gatherings like the memorials for slain transwomen Kyra Cordova and Diamond Williams, Casarez was a ubiquitous speaker, calling for respect for LGBT people and community cooperation.

She delivered mayoral proclamations regularly, from anniversary galas for community organizations to large-scale LGBT events — further emphasizing the city’s backing of the community.

And, she was the point person to connect community members with city officials and resources when needed. For instance, she served as a liaison between the city and Cordova’s family, and represented both the city and community at court proceedings such as for Williams’ alleged killer.

Community roots

Casarez came to the city position after years of community work, including about a decade as the executive director of Gay and Lesbian Latino AIDS Education Initiative.

One of the highlights of her GALAEI leadership was as co-founder of the Trans-Health Information Project in 2003. The peer-based program was one of the first initiatives to offer services — ranging from HIV-prevention to social and legal support around transitioning — for trans people, by trans people, which later became a nationwide model.

After taking on the city position, Casarez maintained, and built upon, her community roots: She sat on scores of community boards and committees, fusing her position as a city official with her inroads as a community leader — from the LGBT Police Liaison Committee to the Philadelphia Convention & Visitors Bureau’s PHL Diversity Board to the Public Health Management Corporation’s LGBT Research Community Advisory Board. She also played a key role in the founding of the LGBT Elder Initiative.

BEHIND-THE-SCENES WORK

As vocal as Casarez was about LGBT rights, she also undertook a wealth of advocacy behind closed doors — campaigning for the LGBT community’s interests at every turn.

Casarez was a constant figure in such discussions as the city’s lengthy legal battle over the Boy Scouts’ use of city property. Casarez even “elbowed” her way into closed-door meetings, to make sure the community had a voice in the debate. She was a unique player in the issue, as she was able to bring the concerns of the community to the table, while delineating the nuanced, complex matter to community leaders and other stakeholders.

She pressed privately, and spoke out publicly, on such issues as the removal of gender markers from SEPTA transpasses and the adoption of a tighter anti-bullying policy by the School Reform Commission, both of which were successful.

Casarez worked closely with a number of city agencies to revise their policies and programs. She assisted the Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual Disability in identifying and working to close gaps in services for LGBT clients; the Department of Human Services to revise its policy on LGBT issues in 2009; and with expanding city domestic-violence services to LGBT and male victims.

Her work also had national implications. In 2012, Casarez spearheaded the legwork for Philadelphia’s inclusion in the Human Rights Campaign’s inaugural Municipal Equality Index, in which the City of Brotherly Love received the highest national baseline score. Casarez helped put plans in motion to help the city attain extra points, such as advocating for Kenny’s bill regarding trans-health insurance, which it did the following year.

Perhaps the most impactful, and hardest to quantify, element of Casarez’s legacy was her success at relationship-building. From arranging meetings among city and community leaders to connecting organizations with city agencies to bringing both city and community services to LGBT people, Casarez broke down barriers. Her personal attributes of warmth, patience and approachability fused with her professional tenacity, candor and intelligence to create a leader our community could look up to, and our city could learn from.

While the full impact of Casarez’s presence in our community is just starting to be realized, her absence has been felt community-wide. But, even after her passing, Casarez continues to be a leader and teacher: Friends and loved ones have made shirts and pins with the phrase “What Would Gloria Do?” a question many have said drives and informs their daily work. Our community will continue to benefit from the many answers Casarez’s legacy will provide for generations to come.

CASAREZ AT THE SIGNING OF THE EQUAL BENEFITS BILL DEC. 12, 2011; THE UNVEILING OF RAINBOW STREET SIGNS IN 2010; AND HER 2011 COMMITMENT CEREMONY TO WIFE TRICIA DRESSEL, OFFICIATED BY MAYOR MICHAEL NUTTER