A National Park Service project has identified hundreds of potential LGBT sites across America that could someday win federal landmark status.

The list, which as of late last month was nearing 400 places, runs the gamut from gay bars and bathhouses to places of worship and LGBT community centers. It includes the homes of prominent LGBT individuals, such as the late gay civil-rights leader Bayard Rustin’s New York City apartment, and several gayborhoods, such as San Francisco’s Castro district and the hamlet of Cherry Grove on New York’s Fire Island.

Last October, as part of its National Park Service LGBTQ Initiative, the federal agency issued a call to historians, preservationists and archivists who specialize in LGBT history to suggest sites that warrant being listed on the national register or designated as historical landmarks.

Megan E. Springate, a queer archaeology graduate student at the University of Maryland, has been compiling the sites on an interactive online map that now contains nearly 300 places of import to the LGBT community. As the Bay Area Reporter, San Francisco’s gay newspaper, reported in January, Springate is working on a National Historic Landmark LGBTQ Theme Study and proposed framework for the National Park Service.

In May, Secretary of the Interior Sally Jewell publicly acknowledged the park service’s LGBT initiative at a ceremony at the Stonewall Inn in New York City. The site of a riot in 1969 credited with launching the modern civil-rights movement in the LGBT community, the gay bar is currently the only LGBT-associated site that has been designated a national historic landmark by the National Park Service.

“I am very pleased the park service has come around to wanting to recognize queer historic sites and I want to do everything I can to help them get those sites processed,” said Mark Meinke, 66, a gay man who founded the Washington, D.C.-based Rainbow History Project.

Meinke has been assisting Springate with her work to locate properties with LGBT historical value that could be nominated for various federal landmark statuses. He is also working on nominating the apartment Rustin lived in at 340 W. 28th St. in Manhattan for listing on the National Register of Historic Places.

Rustin’s partner, Walter Naegle, who still lives in the apartment, is supportive of the landmark status proposal. Because the park service does not recognize individual units, Meinke is working on gathering support from other residents of the co-op to have the entire building be listed on the register.

The International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union built the property in the mid-1950s to house workers in the industry as well as low- or middle-income New Yorkers. The park service has given the entire complex a “declaration of eligibility” for landmarking status, said Meinke.

“Rustin moved in in 1962, a year before the March on Washington, and lived there until his death in 1987,” said Meinke, who expects to present his proposal in March to the New York State Historic Preservation Office. “It should be considered for a national landmark historic status. But the first step is to place it on the National Register of Historic Places, which is a common path to take.”

Five properties recognized

According to park-service officials, only five properties in the country have been granted some form of federal historic preservation recognition specifically due to their relationship to LGBT history. In addition to the Stonewall Inn being deemed a National Historic Landmark, there are four sites presently included in the National Register of Historic Places, described by the park service as “the nation’s inventory of properties deemed central to its history and worthy of recognition and preservation.”

The quartet comprises the Dr. Franklin E. Kameny Residence in Washington, D.C. (listed 2011); the James Merrill House in Stonington, Conn. (listed 2013); and Fire Island properties the Cherry Grove Community House and Theater (listed 2013) and the Carrington House (listed 2014).

In 1957, Kameny was fired from his federal government job for refusing to answer questions about his sexual orientation. Considered “the father of gay activism,” he died in 2011 at age 86.

Pulitzer Prize-winning author Merrill, a celebrated American poet who died in 1995 at age 68, and his partner, David Noyes Jackson, who died in 2001 at age 76, bought their Stonington home in 1956. Merrill wrote almost all of his important works, including 25 volumes of poetry, three plays and two books, while residing in the house.

The Carrington House is considered “an important link” in Fire Island’s development as a gay resort area on the East Coast. The Cherry Grove property opened in 1948 and is considered the country’s “longest continuously operating gay and lesbian theater.”

The next listing will likely be the Chicago home of Henry Gerber, who in the early 1920s formed the Society for Human Rights, the first American gay civil-rights organization. The federal landmarks program is working with University of Michigan at Ann Arbor Professor Michelle McClellan on the nomination for Gerber’s house.

Park officials are eager to see more properties related to LGBT history be nominated, but the agency relies on public individuals to submit the required paperwork before it will consider a property. And a key requirement is having the backing of the current owner(s) of the site in question.

Designation as a National Historic Landmark, for instance, “actually takes some time (it’s a three-to-five-year process); this is compounded by our need to negotiate with property owners (who must agree to nomination and potential designation),” explained Alexandra M. Lord, Ph.D., branch chief of the National Historic Landmarks Program. “That said, we have received a few inquiries regarding some potential sites.”

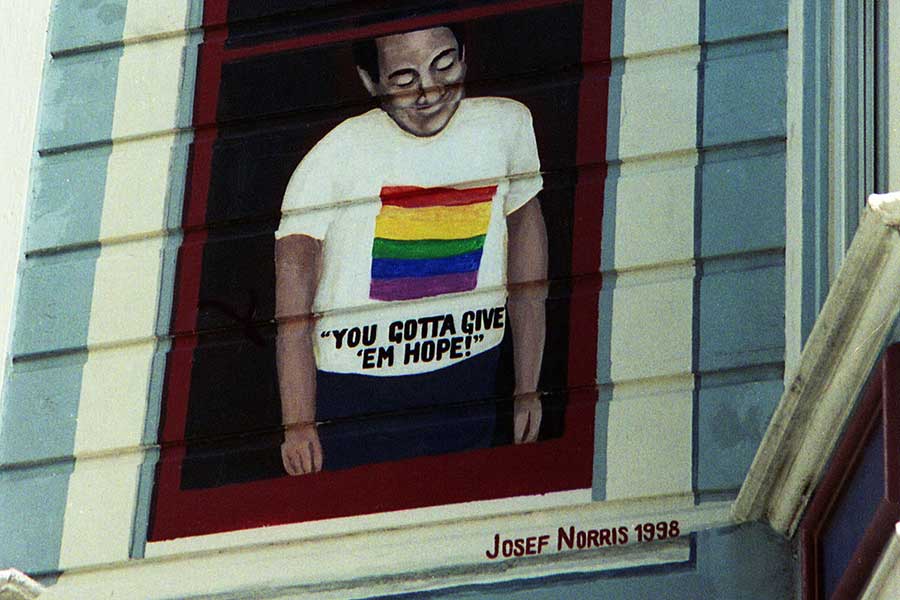

One site that is frequently mentioned as worthy of receiving federal landmark status is 575 Castro St. in San Francisco, where the late gay Supervisor Harvey Milk lived, operated a camera shop and headquartered his campaigns for public office. The property is listed as a city landmark but has yet to be nominated for national recognition.

Local preservationists are first waiting for the completion of a historic context statement for the city’s LGBT community, expected to be finished in early 2015. The local planning document is considered the first step toward preserving places and structures of significant LGBT historical value and is often referred to by government agencies when determining requests for historic preservation designations.

“I am less anxious about reaching the point of having sites in San Francisco listed on the national register or be nationally landmarked; that will be fairly readily accomplished,” said local historian Gerard Koskovich, who is on the advisory committee for the historic context statement project. “It is places outside of San Francisco that need an extra boost and helping hand. That part of our history is less well-known, and it is intriguing to me to learn about those sites outside of San Francisco.”

Koskovich, who has also been helping Springate locate LGBT historical sites for her National Park Service project, said one step federal officials could take is to update the listings of already-landmarked sites so that their ties to LGBT history are added and highlighted.

“A strategy many of us are looking at is the amending of the historical description of sites already listed on the national register. A number of which, including here in San Francisco, have a gay history connection, but it is not mentioned in the original designation,” he said. “It is easy to imagine the national register, with 80,000-plus listings, has dozens, if not possibly hundreds, of sites already listed for other reasons that also have a significant LGBT history.”

For more information about the National Park Service LGBTQ Initiative, including a link to the interactive map of LGBT historic sites, visit http://www.nps.gov/heritageinitiatives/lgbthistory/.