San Francisco’s Tenderloin neighborhood has a colorful history and was once the center of gay life in San Francisco. Grittier than the Castro, which in the late 1970s overtook “The Loin,” as it’s sometimes called, as the city’s gay hub, the neighborhood just blocks away from City Hall also has a well-worn reputation for drug dealing, robbery and other crimes. It’s home to some of the city’s poorest residents, many of whom are living with HIV and stay in the district’s single-room occupancy hotels.

The neighborhood is bounded by the historic Beaux-Arts City Hall on one side and Union Square’s upscale hotels and shops on the other. Most of the gay bars, theaters and bookstores that once filled the Tenderloin are gone, but a handful have survived, and many LGBTs still express fondness for the area.

One business that’s held on since the 1970s is the Tea Room Theatre, 145 Eddy St. The tiny lobby has pictures of movies with titles like “Cum Smack 2,” and a sign warns, “J/O [jacking off] only is allowed in the theater.”

Inside the small, dark auditorium on a recent Friday afternoon, it would have been impossible to see without the light from the porn being projected onto the screen.

In a couple of seats at the front, one man on either side of the aisle was giving head to his seatmate, disobeying the sign in the lobby.

During an interview in which he spent the first several minutes standing behind the metal gate that separates his office from the lobby, Steve Angeles, 50, praised the Tenderloin, the neighborhood he calls home. The area is “very friendly,” he said, and it’s “the real San Francisco.”

Angeles, who’s worked at the theater for five years, said, “I really don’t know” why the business has survived, but it’s “probably” because it’s a short walk from two BART transit stations. Plus, “we show all the brand-new movies every week, and we are friendly,” he said.

Business appears to be brisk. Customers include men from out of town and regulars from the neighborhood.

“When they retire, they have nothing to do, just relax,” Angeles said of patrons. “People feel at home here.”

At 35, Marc Woodworth is likely one of the Tea Room’s younger fans. Woodworth, who lives in Europe but is in San Francisco six months at a time, comes to the theater once or twice a month. There’s “no other place to go” in San Francisco, he said.

Angeles, who doesn’t identify with a specific orientation but said, “They call me Mama Steve,” noted the current lease is up in 2015.

“Hopefully,” he said, the building’s owners will give the theater “another few years.”

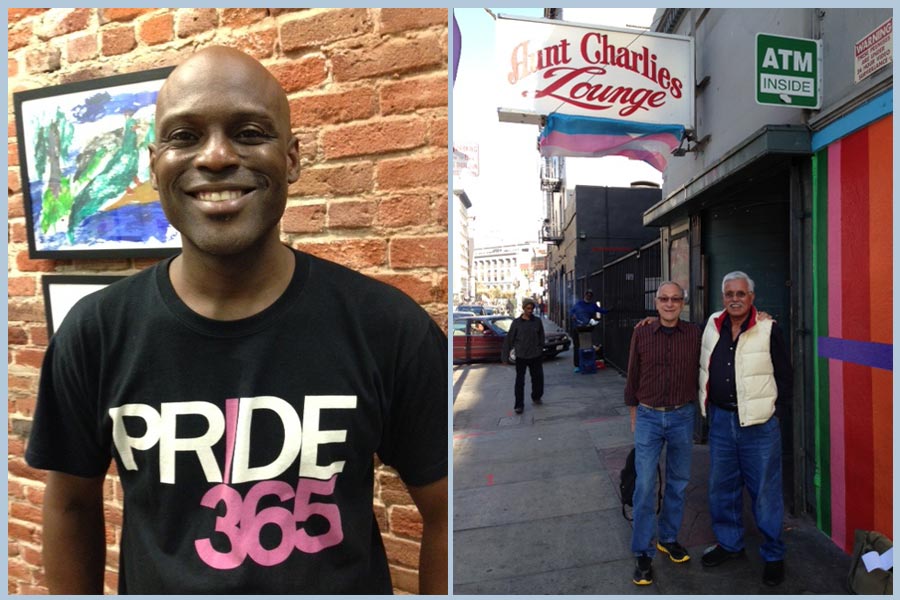

About a block from the Tea Room, soul music played inside Aunt Charlie’s Lounge, 133 Turk St., as Louie Lopez, 74, and Paul Lee, 73, stood outside.

The gay men listed the bars that used to be nearby, like the Blue and Gold and the Landmark, and the people they used to see there.

“There was always something going on,” said Lopez, who lives in the neighborhood and started coming to Aunt Charlie’s almost 30 years ago when it was still Queen Mary’s Pub.

Lee said the neighborhood “was like a candy store” when he first came in 1976. “It was so much fun.”

However, he noted, “there was a lot of prejudice against people from the Tenderloin,” and there still is.

“If you just tell someone you used to hang out here, they say, ‘But you don’t go there anymore, do you?’” Lee said.

Inside Aunt Charlie’s, the narrow walkway between the bar and some tables and benches frequently doubles as a runway for drag performers as they lip-sync to songs and collect tips.

Joe Mattheisen, 65, a gay Tenderloin resident, has worked at the bar for about 16 years.

Mattheisen said one reason the business has outlived many others is that it’s not “the sole source of income” for its owner, unlike other establishments. Over the years, the bar has also added drag shows and DJs.

Queens and hustlers

The block where Aunt Charlie’s sits was recently named Vicki Mar Lane, after Vicki Marlane, a transgender woman who performed there for years before she died in 2011 at age 76 of AIDS-related complications.

Felicia Elizondo, 68, a close friend of Marlane, first visited the Tenderloin in the early 1960s, and said she hasn’t noticed much change in the neighborhood since then.

Elizondo, a transgender woman who lives in another neighborhood now, recalled the area being packed with “queens” and “hustlers.” People made money by “selling drugs and selling themselves,” she said, and the district was “very dangerous.” (Elizondo said she didn’t deal drugs but she did work as a prostitute.)

Someone could get “thrown in jail for obstructing the sidewalk” and people would get “beat, murdered or raped” by “tricks or people that just didn’t like gay people,” she said.

Elizondo remembered a woman named Rhonda who died after “one of her tricks cut her breast out.” She didn’t know Rhonda’s last name.

“When you came to San Francisco, you came to San Francisco to start a new life,” she said. “You weren’t nosey. Most people wanted to forget the past.”

Elizondo also recalled Compton’s Cafeteria. The 24-hour cafe at the corner of Turk and Taylor streets was the site of an August 1966 riot where transgender patrons stood up against police, who had been called to quell a disturbance. The exact date of the riot has been lost to history.

A ceremony in June 2006 featured the unveiling of a commemorative sidewalk plaque at the former Compton’s location, which was timed with the 40th anniversary of the riots, which predated by three years the more-famous Stonewall Inn rebellion in New York City.

The Compton riot is widely viewed as the beginning of the LGBT-rights movement in San Francisco, but Elizondo said that at the time, it didn’t have a noticeable impact.

“Everything went back to the same old way,” she said.

Almost 50 years later, though, some things have changed.

In the lobby of the Tenderloin police station, about a block away from the Compton’s site, a sign assures visitors that the space is an “LGBT safe zone.”

Captain Jason Cherniss, 44, who’s straight and heads the station, wasn’t familiar with the details of the Compton’s riot, but he expressed support for the LGBT community and enthusiastically spoke of how, when he was in college, he examined the Castro’s evolution as a gay mecca.

The San Francisco native’s biggest public-safety concern in the Tenderloin is drug dealing. Anyone who’s walked through the neighborhood probably has stories of being approached by dealers, and the station’s newsletter regularly lists incidents for sales of cocaine, heroin and other drugs.

As for what to do about it, Cherniss said, “we’re not going to be able to arrest our way out” of the problem, but he keeps officers “visible” and encourages property owners not to leave locations “blighted.”

In his September newsletter, Cherniss featured gay Tenderloin resident Aja Monet, 44, as the Citizen of the Month.

Among other activities, Monet, who is HIV-negative, sits on the HIV Prevention Planning Council, an advisory group to the city’s health department that sets priorities for HIV prevention. He’s also hoping to have an LGBT Pride event in the Tenderloin next year.

Monet, who came to San Francisco in 1988, said that he used to smoke crack and worked as a prostitute “off and on.”

Now, he’s been off drugs for five years and he works on graffiti removal and other issues in the area. The neighborhood hasn’t been as impacted by development as the Market Street corridor just a few blocks away, but he thinks more development is coming to the Tenderloin.

“They’re running out of places to build,” he said.

Monet didn’t show any interest in leaving the district, and he said he feels “very safe” there.

“I think somebody called me a motherfucking faggot” a few months ago, but “that was someone that didn’t know me,” he said. “People in the neighborhood … they don’t talk like that.”

Seth Hemmelgarn is an assistant editor at the Bay Area Reporter. He can be reached at [email protected].