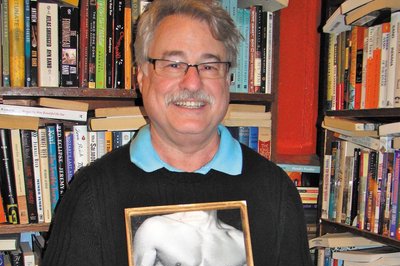

In 1982, being diagnosed with HIV/AIDS was pretty much a death sentence. Thankfully, this week’s Portrait, Harry Adamson, has defied the odds and joined me to talk about his 33 years in the City of Brotherly Love and Sisterly Affection.

PGN: So are you a Philadelphia person? HA: I am now. I came here in 1981 because I had a partner who got a fellowship at Temple’s medical school. He moved back to Ohio after he finished and didn’t want me to return with him. So I stayed and I’ve made wonderful friends here. I feel like Philly is my home. It is my ancestral home because my ancestors were Quakers who had been imprisoned in Newgate Prison and came here in the 1680s.

PGN: Where were you born? HA: I was born in Kansas City, Mo. All of my grandparents were born on the farm; in fact, my parents were the first generation off the farm. My dad was a cop most of his life and my mother was a court stenographer. They met at a dance at the police union, dated for a while, married, had my sister, then the war came along and my father was stationed in the South Pacific. Navy. Pretty horrible places like Okinawa and Iwo Jima. He was a pretty personable person but that’s the one subject he wouldn’t talk about. It’s funny. I’m the only one in the family who is not a cop. My father, his brother, my brother, his brother-in-law, my nephew — it’s kind of the family business.

PGN: How many siblings? HA: My sister, Kathleen, is 10 years older and my brother, Patrick, is three years younger.

PGN: Was the gap because of the war? HA: Kind of. After my father got home they had a child that was stillborn and it affected my mother for the rest of her life. There was a big hole in her from then on.

PGN: So you grew up in Kansas? HA: When I was about a year old, my parents moved to Southern California for a few years. My father worked for Flying Tigers Airline and I have some luscious memories of a long-gone L.A. The colors were just magnificent. Then we moved back to the Midwest. My father died of a heart attack when I was about 12 and my mother died of a stroke when I was 16. My sister was married by that time so my brother and I stayed with her. Then I went to college and my brother moved in with an uncle who lived in Florida. High school had been difficult for me because there was just so much going on in the family but college was great. I went to a Jesuit school and really blossomed there. The Jesuits found a place for me to live with an elderly widow. She’d been married twice and both of her husbands were journalists who had won Pulitzer Prizes. The first husband had been President Truman’s press secretary and died at his desk in the White House. So she would have these amazing visitors from the intellectual, journalism and political worlds.

PGN: Most memorable? HA: They were all pretty amazing but one of my top three would be Earl Warren. He was such a nice guy. And a natural teacher; he loved to talk to young people.

PGN: What was the hardest part of losing your parents at such a young age? HA: I don’t know. When you’re that young, you don’t really think about it. You’re just trying to cope. Fortunately, I had my sister and my uncle, who filled the father role as much as he could. I think not having them around in my adulthood to talk to was harder. I have to give mention to my teachers at my Catholic high school and college who were great to me. My college mentor — a brilliant priest — became a great friend and made a big difference in my life.

PGN: What did you study in school? HA: My majors were philosophy and literature. I was planning on being either a lawyer or a Jesuit, but neither panned out! But I did get a master’s at La Salle University in pastoral counseling and taught high school for a while. I also worked for the Kansas City Star newspaper. My boss there was a very odd fellow who used to hire people with great promise and then when he got nervous that they would take his job, he would fire them. They used to call it the Murder of the Princes.

PGN: I take it you were a murdered prince. HA: Yes. Then a college friend got me a job in Chicago at the Mercantile Exchange, and I worked as a trader on the cattle desk. It was a great adventure.

PGN: I just had a vision of you on the phone yelling, “Buy, sell!” HA: [Laughs.] Yes! This was before high-tech computers so we used a punchcard that was fed into the computer at the end of the night. I’m still in touch with that friend and we talk almost every day. We are like yin and yang. He’s a straight jockish guy and I was the quiet intellectual, but we met in the fraternity and just hit it off.

PGN: What fraternity was it? HA: Alpha Delta Gamma. I was president in my sophomore and junior years. [Laughs.] I think they elected me because they thought I had some connections with the administration and could mitigate some of their shenanigans.

PGN: Like what? HA: Oh, one year they stole a bunch of Christmas trees and didn’t realize that when they dragged them back they left a trail in the snow leading right back to the house. When the authorities came, they tried to burn them and the whole place smelled like burnt evergreen!

PGN: Any hazing? HA: We had to wear a gunnysack under our clothing and a necklace made of garlic. One time, they took us to the park and made us dig a hole and get in. They filled it with water and pissed in it and made us splash around in it, then we had to walk 5 miles back to the school covered with mud and piss. There was nothing really dangerous. We did have to make a paddle for our pledge fathers to use on us, but it was mostly play-acting.

PGN: When did you come out? HA: After I left Chicago I moved back to Kansas City and started working in a restaurant. One time after work, a coworker took me to a gay bar. I’d never really done anything in the community before. After a few visits I met a young fellow and we dated for about three years. He was a classical and jazz pianist and we stayed in touch until he died of AIDS in 1986. After Greg, I met David, a physician who was in Kansas City for a meeting. In 1981, we moved to Philly and stayed with a friend of his who was a professor at Temple, Dr. John Fryer. He was a brilliant man and clinician; he could tell you what was wrong with you from across the room — mentally or physically! He was a professor of both psychiatry and family practice. He was a big guy — about 6-foot-4, 300 pounds with a booming voice — but he was very humble. I didn’t know that he was Dr. H. Anonymous until the last year he was alive and he received the Distinguished Service Award from the Association of Gay and Lesbian Psychiatrists.

PGN: When were you diagnosed? HA: In February of 1982. David had been in New York, and a little bit later I came down with a very strange flu. I had a big rash and I’m not the type to get rashes. Even Dr. John was stymied by it and sent me to a tropical-disease fellow. They didn’t know what to call it — they called it an echovirus [laughs], which certainly was the right word, since it continues to echo years later. In retrospect, I’m sure those were the first symptoms. When I went to work for Philadelphia Community Health Alternatives in 1985, I was part of that first group trained for HIV counseling and phlebotomy. The week before Thanksgiving, we all tested each other. I got the positive results the day before Thanksgiving. I was astounded. I thought I’d lived a pretty quiet life but both Greg and David had been much more active than I was … before, during and after our relationships! Greg died in 1986, David died in 1995. My physician was the legendary John Turner, who pioneered AIDS care. I was in his first grouping of patients for the Salk vaccine and I tried to recruit my friends to be part of the trial but they didn’t think it had any future. The study was stopped abruptly — I think there were a lot of politics behind it — but I think the study is one of the reasons why I’m still here. I found out later that I was on a placebo but the method of the delivery that they used, an adjuvant, had immunological-positive properties that truly made a difference.

PGN: People seem almost blasé about it now. Describe what it was like receiving a positive diagnosis back then. HA: It was terrifying. The protocol back then was to tell people that they had six months to two years to live and to get their affairs in order. People were keeling over left and right all around you. I don’t know, maybe growing up Catholic gave me enough denial that I sailed through it better than most, but I had great confidence in Salk and Dr. Turner. After Turner retired, I went to Steven Hauptman, who has kept close tabs on me ever since. I have to credit good doctoring and fortune or providence for keeping me alive. I worry about the kids who are so cavalier about it now; we still don’t know the long-term implications of the medicines they’re taking and there are emotional and physical consequences. The HIV ads that you see show these buff fellows mountain climbing, strolling along the Eiffel Tower without a care, but it’s a lifetime of daily pharmaceuticals and medical involvement. You have to be very strong to be able to keep it up for a lifetime. There’s also the monetary cost, fighting with insurance companies, etc. That’s always been a big bugaboo for me, keeping ahead of the game. Hopefully with Obamacare, that won’t be quite the problem it once was.

PGN: When did you first figure out you were gay? HA: Well, it was difficult back in the ’50s and ’60s and even the ’70s. There were no role models. The only gay people you saw were horrible stereotypes. In my neighborhood, there was a nationally famous bar called the Jewel Box. Little did I know, it was a bar with drag performers. There was a woman I would talk to at the soda fountain when I went after school. I remember her being beautiful and elegant, and I don’t know how but one day I realized that she was a man. It freaked me out back then. I’m glad that today kids have role models of all sorts and can see other gay/bi and trans people out there to identify with. I didn’t come out until I left town and came back.

PGN: Tell me about the early days with PCHA. HA: We started out in a little house on St. James Street. It was a teeny, two-bedroom trinity and we did testing on the second floor. We did everything. I was directing the AIDS Hotline for a long time and wrote the newsletter.

PGN: A memorable call you took? HA: Ha! The memorable ones were the chronic callers. There was one guy who had been downtown and received oral satisfaction from a lady of the street. Afterwards he realized she was not 100-percent lady. He called us every day for a year! We tried to be patient with him because he was so freaked out, we were afraid he might harm himself. Another one was a woman from the Main Line who had gay neighbors. She called frequently because they had a cat and she was afraid that the cat would spread AIDS to the neighboring community. But my favorite was a fellow who called one day and said, “You have to send the AIDS wagon up here! We got this guy who’s got the AIDS and he’s going house-to-house, screwing everybody on the street!” He said, “What am I going to do?” I said, “Don’t open the door.” [Laughs.] That was great fun for us. We envisioned this big pink bus that said, “The AIDS Wagon,” blaring disco music with a big mirror ball.

PGN: That’s great. So, random questions … What book would you put into a time capsule? HA: Oh, I think it would be “Four Quartets” by T.S. Eliot.

PGN: Historical moment you remember best? HA: I used to work in the Truman Library and, as I mentioned, I knew a lot of his people from the widow I lived with. When Truman died, his secretary arranged for me to stand on the porch of the library as he lay in state. I had an amazing view of all the dignitaries who came in to pay their respects. Lyndon Johnson, Hubert Humphrey (one of my favorites) and Richard Nixon, who was in full make-up and his hair was down, almost like a hippie!

PGN: Best gay bar? HA: The Diamond Bar in Omaha, Neb. I think in rural places where there’s not anywhere else to go, people come from miles away to the one gay bar and it’s great because they can drop their pretenses and be themselves. Ha. I just had a flashback of a very large drag queen named Lindsay who used to terrorize me. She was well over 6 feet and had a thing for me. She was resolute in the fact that we were going to live together forever with a white-picket fence. [Laughs.] I still shudder when I remember her in her red gingham dress!

PGN: So what things do you like to do now? HA: I love to read and I love volunteering at the Book Trader. The owner, Peter, is an old friend and the people there are great. I’m also a big walker; it’s good for the soul and clears the head. And crosswords, I’m a big crossword enthusiast and look forward to the Sunday Times puzzle each week. I take it down to the laundry room and it helps pass the time.

PGN: And that’s in the new John Anderson building correct? HA: Yes, it’s really great. Some friends of mine talked me into going through the process and I’m glad I did. Long ago I spent my money thinking I would be dead soon. I have Social Security but my personal pension will be running out in the near future so this came along at just the right time. All the people here are just lovely and it’s been a great experience. The garden is going to be a wonderful, safe place for us to hang out this summer.

To suggest a community member for Family Portrait, email [email protected].