With a stroke of a pen 40 years ago, LGBT people were “cured. ”

In 1973, the American Psychiatric Association made the groundbreaking move of declassifying homosexuality as a mental disorder, after a lengthy campaign by such activists as Frank Kameny, Barbara Gittings and Kay Lahusen.

Yet one of the key factors thought to have spurred the policy change was a speech at the 1972 APA convention in Dallas — in which “Dr. H. Anonymous,” clad in a mask, wig, baggy clothes and using a voice-altering microphone, became the first gay American psychiatrist to speak publicly about his sexual orientation.

Now, 40 years after the APA’s decision, Dr. Anonymous’ seminal speech continues to open eyes.

The original copy of the speech has been digitized and included on the Historical Society of Pennsylvania’s new Preserving American Freedom website, launched in September, which highlights 50 historic documents that examine the tenets of American freedom.

The speech was discovered among the more-than 200 boxes donated to HSP by the sister of Dr. John Fryer, the man behind Dr. Anonymous’ mask. Fryer was a Temple University professor and one of the founders of the Philadelphia AIDS Task Force. Upon his 2003 death, his sister donated his papers to HSP.

In 2011, as the collection was being processed as part of a civic-engagement project — an effort supported by the National Historical Publications and Records Commission — Willhem Echevarria, HSP cataloguer who was then an archival processor, made the surprising discovery.

“We were of course aware of Fryer’s speech to the APA but when we were processing it, we weren’t aware the actual handwritten speech was in the collection,” Echevarria said. “So when I found it, that was a big moment. You love those moments when you can find something historically important right there in front of you.”

HSP houses thousands of documents at its Philadelphia headquarters, and functions not as a museum but as a library and archives: Researchers, educators and anyone with a knack for history can come in and peruse the collections in person. About 77,000 of its documents are preserved in a digital database to promote wider viewing.

When HSP was compiling selections for the Preserving American Freedom project, which is funded by Bank of America and which also includes such items as a handwritten draft of the U.S. Constitution and William Penn’s 1682 deed with the Delaware Indians, Fryer’s speech stood out as a natural fit.

“The history of gay rights in America is an emerging history, and it’s an exciting emerging history,” said Rachel Moloshok, Preserving American Freedom project manager. “And this document is very groundbreaking; it speaks to the need for the freedom of gay men and women to live openly, freely and honestly without being stigmatized as mentally ill.”

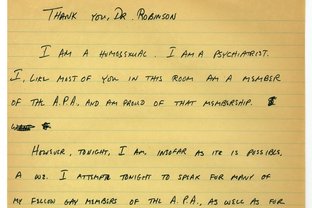

The nine-page speech was written in felt-tip marker on yellow legal paper and includes a number of scratched-out words and rephrasings, allowing the viewer to follow Fryer’s thought process.

In some places where Fryer had initially written in past tense, he changed the words to present tense, perhaps to communicate the ongoing impact of antigay sentiments, and he also modified singular first-person pronouns to plural, seemingly to emphasize that he was not alone in his petition.

The speech itself details the myriad pressures that LGBTs working in the psych field faced keeping their personal and private lives separate, including the threat of persecution from employers to which they were loyal.

“Many of us work 20 hours daily to protect institutions who would literally chew us up and spit us out if they know, or chose to acknowledge, the ‘truth,’” Fryer wrote.

He finished his address by speaking directly to his fellow LGBT psychiatrists, an informal club he dubbed “The GayPA,” urging them to speak out against anti-LGBT comments from their colleagues, to remain objective when treating LGBT patients and to “pull your courage up by your bootstraps and discover ways in which you as homosexual psychiatrists can be appropriately involved in movements which attempt to change the attitudes of both homosexuals and heterosexuals toward homosexuality.”

Throughout the online exhibit, viewers can zoom in on documents, scroll across them and read histories about the context of each piece.

“We think primary-source documents like this speech, where you can look directly at the words as they were written, are really valuable,” Moloshok said.

In addition to Fryer’s speech, the initiative also includes an original brochure of the 1968 Annual Reminder at Philadelphia’s Independence Hall, one of the nation’s earliest LGBT-rights demonstrations.

And many of Fryer’s other papers have been digitized in HSP’s online database and are available for view in person at the archives.

Echevarria did caution that HSP had to put certain restrictions on some of his papers that included patient information. But, other personal documents include entries from his diary from the day after the APA speech, letters between him and Kameny and correspondence with the APA when some association leaders attempted to reinstate antigay policies.

“We also have a very rich collection regarding the history of AIDS in Philadelphia,” Echevarria said. “He was really the first psychiatrist who treated patients with AIDS. There’s a lot of information about the epidemic hitting Philadelphia, very rich information.”

Moloshok noted that the Preserving American Freedom project gives viewers — whom she envisioned to be everyone from students of all ages to anyone with a passion for history, politics or civil rights — a slice of the wealth of historical artifacts HSP houses.

“These are just 50 documents of the thousands and thousands we have,” she said. “This hints at the depth and breadth of the content we have in our collections. I do hope it’ll inspire people to dig deeper, start asking more questions and do more research.”

To view the Preserving American Freedom project, visit http://digitalhistory.hsp.org/preserving-american-freedom and, for the entire speech, see http://digitalhistory.hsp.org/node/7484. To learn more about HSP or view the full digital database, visit www.hsp.org.