Does health for health’s sake move us to be healthy, or do moral implications and societal scrutiny play into our motives?

We often draw conclusions about people’s moral character with respect to how healthy they appear. Even something as pedestrian as cleanliness can affect our outlook, though some traits are more forgivable than others.

An alluring musk is sexy while pungent body odor signifies slovenliness; a hint of tobacco on one’s breath can be charming while halitosis urges disassociation; even a gap in the front teeth (which in the Middle Ages betokened equivocation and turpitude) can inspire a sense of distrust often linked with deviance.

These traits pose far greater threats to social image than bodily health. And if something as benign as outward uncleanliness can make us cast judgment so easily, what can inner, often more pervasive uncleanliness, such as HIV, cancer or mental afflictions, make us do?

Because of my HIV status, I am considered unclean. Why? Because my dirtiness can sully the health and morality of others, who do not deserve the mark of uncleanliness? Because people fear the fate of poz people, and marking them as sick makes avoiding that fate easier? What is that fate, exactly?

In sickness or health, life or death, piety or wickedness, wealth or poverty, ranking the humanness of humans based on traits humans can exhibit only creates fear, revulsion, hostility and separation; for in truth, how can anyone ever be any less than human?

One might say, “But people cease to be fully human when they act inhumanely. Are you saying that bad people don’t exist, or that people should never change? What about personal growth? What about learning to be selfless?”

Is humanity irrational at its core? If law, religion and morality didn’t enforce ethical living, would we all just run around fucking and killing each other? Has humanity’s plight been one of perpetual conflict against its natural compulsion to destroy itself?

No. Absolutely not. In fact, law, religion and morality, specifically the kinds crafted after the supposition that humans are inherently irrational, create an abhorrence of and destruction towards humankind.

On the contrary, humans seek community and love.

People act inhumanely not out of an inherent desire to indulge or destroy, but in hopes that the unquestioned practice of an abstract ideal (e.g. law, religion, morality, etc.), self-conceived or secondhand, will deliver the very community and love they originally sought, before someone or something told them that they would never acquire these on their own.

What begs the question now is how can we progress towards a compassionate framework of thought and action regarding the sick while exploring why our existing frameworks remained couched in prejudice and revulsion?

In my last article, I elicited the dual reaction we have towards the sick: We distance ourselves from and draw nearer to help the sick out of self-preservation and communal sentiment, respectively.

But are self-preservation and communal sentiment mutually exclusive?

If we assume that humans are inherently irrational, and that communal sentiment is merely a product of law and morality, then the two would be mutually exclusive. But, if we assume that humans are inherently rational, then self-preservation and communal sentiment aren’t merely compatible, but inseparable parts of a whole — ones mutually beneficial to ameliorating sickness in others.

But this benefit also calls into question why we mark people as sick in the first place. Is it possible that we do so to affirm our own mark of healthiness? What would happen if our current health-care models did away with this distinction?

Health care would radically transform into a pluralistic culture of wellness based in a continuum of celebration, openness and community engagement, instead of a culture locked in warfare against sicknesses that render us inhuman.

Instead of dreading doctor visits in fear of being marked as sick, people would be excited to talk openly about their lives and co-create programs for wellness with their doctors. Instead of avoiding health education in fear of discovering that they themselves might be sick, people would crave knowledge about a diversity of health issues and engage each other in compassionate dialogues about the community’s health at large.

How would your self-image change if you were never marked as sick, but always on the path towards wellness?

We’re all in this together, folks. Now get out there and talk about it.

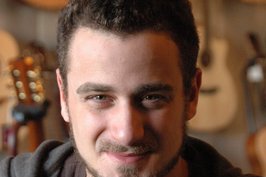

Aaron Stella is former editor-in-chief of Philly Broadcaster. He has written for several publications in the city, and now devotes his life to tackling the challenges of HIV in the 21st century. Millennial Poz, which recently won first place for excellence in opinion writing from the National Lesbian and Gay Journalists Association and best column writing from the Local Media Association, appears in PGN monthly. Aaron can be reached at [email protected].