On Aug. 5, 1982, Philadelphia City Council took a historic step in the gay-rights movement — one that continues to resonate with and protect the city’s LGBT residents today.

In a 13-2 vote, Council amended the city’s Fair Practices Ordinance to prohibit discrimination based on sexual orientation in housing, employment and public accommodations.

Thirty years later, hundreds of LGBTs have sought recourse from the city for instances of discrimination — with some complaints leading to fines and, others, an increased awareness of the city’s legal support for its LGBT residents.

The road to that legal backing, however, was a long time coming.

Political, social context

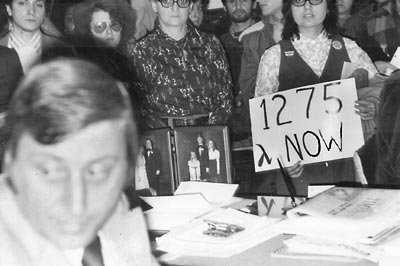

The effort to include sexual orientation in the human-rights law began in 1974, but that first incarnation died in committee in 1975. The failure spurred a protest in City Council chambers by Dyketactics members, in which protesters alleged police brutality.

After the loss, activists remobilized in the late 1970s to demonstrate to elected officials the value of the gay and lesbian voting bloc, with the goal of getting their electoral support matched by support for gay rights.

In the 1979 mayoral race, a number of LGBT activists rallied behind contender Councilman Lucien Blackwell in his mayoral bid against eventual winner Bill Green.

“We knew he didn’t have a chance, but we thought that if we could demonstrate that there was a gay vote that supported Blackwell in places like Center City, we’d be able to distinguish the gay vote in a way that hadn’t been done before,” said David Fair, co-founder of the Philadelphia Lesbian & Gay Task Force.

And, despite Green’s victory, Fair said the effort was successful, as a number of divisions heavily populated by gays and lesbians went to Blackwell.

The following year, activists also succeeded in helping a number of out politicos get elected as ward leaders.

The federal public-corruption investigation known as Abscam — which ultimately resulted in the conviction of several federal and state officials — also led to the arrest and ousting of several Philadelphia councilmembers, including Council President George Schwartz, Majority Leader Harry Jannotti and Councilman Louis Johanson, paving the way for new blood.

“That allowed a much more liberal and progressive group, led by a number of African-Americans, to move on to Council,” said Dr. Larry Gross, former co-chair of PLGTF. “Had the old power group that was running the city in the mid-’70s still been in place, I don’t think we could have succeeded with the passage of the bill. We took advantage of that change in the landscape, and that was key.”

Those developments, as well as an overall heightened involvement in city campaigns by the gay and lesbian community, were integral in pushing the gay-rights ordinance to the forefront of elected officials’ consciousness.

“We had worked hard to support a number of new members and to build good relationships with councilmembers in the years before 1982,” said PLGTF member Scott Wilds. “So we had been working for some time to set the stage.”

Building relationships with African-American councilmembers and political leaders was especially important, Fair said, as city Managing Director W. Wilson Goode was gearing up to launch a 1983 campaign to become the city’s first African-American mayor.

“We wanted to put this issue on the agenda of elected officials, and those who wanted to be elected officials, as something that we wanted to get resolved soon or otherwise it would become a major issue in the 1983 mayoral election,” Fair said, noting the lawmakers with whom they worked cautioned that the campaign should stay low-key.

“The major piece of advice that we got from black councilmembers was that to get the bill passed, we should mobilize in the gay community and not anywhere else. Our best bet was to not give opposition the opportunity to jump on this and make a big issue out of it.”

The lobbying effort was led largely by PLGTF, helmed by executive director Rita Adessa, with strong collaboration by groups like Philadelphia Black Gays, led by Doug Bowman.

Despite the inroads they made with councilmembers, the activists recognized that, to be successful, they had to demonstrate the widespread need for and impact of the gay-rights ordinance.

Throughout the spring of 1982, lobbyists organized letter-writing campaigns in each councilmanic district and mobilized residents throughout the city — especially in areas outside of the traditional gay neighborhoods at the time — to contact the at-large councilmembers.

“We tried very carefully to get people to write letters who lived in parts of the city that might have been thought of as non-gay,” Wilds said. “When Council people got 50 letters, they really took notice. And then when they saw addresses that were in their districts or when they were places like Germantown, West Philadelphia or Overbrook, places not thought of as hotbeds of gay residency, it made a difference.”

In-person meetings with nearly all of the councilmembers were held as summer approached, with lobbyists accompanied by district residents who would detail why such a law was essential.

“There were still a lot of complaints coming in to the Task Force at that time, and people were much less sophisticated than now in covering up their homophobia and their animus toward gay people,” Fair said.

Moving to a vote

Blackwell introduced Bill 1358 on June 30 with nine cosponsors on board, the exact number needed for passage.

The measure was put to a July 27 hearing before the Council Committee on Rules.

Fair said that Council President Joe Coleman strategically scheduled the hearing with little fanfare — and at a time when Archbishop John Cardinal Krol was out of the country.

Ultimately, 55 people testified — all of whom were in favor of the bill.

Among the witnesses were two men who would become the city’s next mayors — Goode and then-District Attorney Ed Rendell.

Goode told councilmembers that the legislation would provide “basic civil and human rights afforded to all citizens of this country,” while Rendell testified to the validity of the gay and lesbian community in a statement that was telling of the times.

“The gay community in Philadelphia are as productive as any community. They are taxpayers that work hard,” Rendell said. “We receive virtually no complaints against any gay man or woman for any sort of sexual abuse of minors or any other non-consenting adults.”

The witness list also included a wealth of local and national LGBT activists; leadership from the University of Pennsylvania, which a few years before had adopted its own nondiscrimination ordinance; and a collection of local progressive religious leaders.

“It’s a chess game,” Gross said. “One side puts their community leaders on the board, you put your community leaders on the board. One side puts their clergy on the board, you put your clergy on the board. We were able to bring to bear effective and well-respected clergy such as Paul Washington, a longtime African-American minister who was a leader in the civil-rights movement, as well as other rabbis and ministers. We had to put forward people who would speak for the community and tell City Council that things are changing and that they should be at the forefront of that change.”

After the three-hour proceeding, six of the seven committeemembers voted to send it to the full Council.

While the measure appeared fast-tracked to passage, there were a number of lingering questions. During his 1979 mayoral campaign, Green pledged to support a gay-rights ordinance. However, in the weeks leading up to the summer of 1982, he had become close-lipped about the bill.

Without the guarantee of mayoral approval, activists were left to question if they had enough support to override a potential veto.

And, while enough councilmembers pledged to vote for the bill, Wilds said activists were not 100-percent confident those lawmakers would wage battle if opponents came out swinging.

Nonetheless, a vote was scheduled for Aug. 5, and supporters gathered en masse to prepare for what they hoped would be a historic day in Philadelphia.

Next week: The vote and impact of Bill 1358.