One of the rewards of time is that eventually everything becomes public. While the 1973 disruption of the “CBS Evening News with Walter Cronkite” has been known for years, much of it has not been made public until now, in esteemed author Douglas Brinkley’s new best-seller, “Cronkite.”

Last Sunday on CNN, Don Lemon interviewed Brinkley on the book (link below). His last question was, “Are there any surprises in the book?” Brinkley mentions the disruptions and my friendship with Walter that followed and, for the first time, reveals that CBS news executives, under the direction of Walter, then took steps to assure the fair and unbiased coverage of the gay and lesbian community. In a sense, I became a consultant to CBS News and Walter on the subject. It is also a timestamp for gay history, since it was the first time attitudes in broadcast media began to change. This was long before “Ellen” or “Will & Grace.” It was a time when there were no LGBT characters on TV or only negative news. GLAAD hadn’t even been founded. This was the very beginning of that change, and Brinkley captures it well. Brinkley gave me permission to print an excerpt from the book; for Lemon’s interview with Brinkley, go to CNN.com and search for “Cronkite’s cozy White House relations.” Brinkley talks about me and the Gay Raiders at 4:15 in the video. Hope you enjoy.

From “Cronkite,” by Douglas Brinkley:

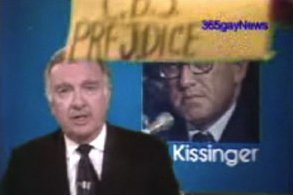

The days of lax security at CBS News abruptly ended on Dec. 11, 1973, when 23-year-old Mark Allan Segal, a demonstrator from an organization called the Gay Raiders, with accomplice Harry Langhorne at his side, interrupted a Cronkite broadcast, causing the screen to go black for a few seconds. Cronkite was delivering a story about Henry Kissinger in the Middle East when, about 14 minutes into the first “feed,” Segal leapt in front of the camera carrying a yellow sign that read, “Gays Protest CBS Prejudice.” More than 60 million Americans were watching. Segal had insinuated himself into the CBS newsroom by pretending to be a reporter from Camden State Community College in New Jersey. He had been granted permission to watch the broadcast live in the studio. “I sat on Cronkite’s desk directly in front of him and held up the sign,” Segal recalled. “The network went black while they took me out of the studio.”

On the surface, Cronkite was unfazed by the disruption. Technicians tackled Segal, wrapped him in cable wire and ushered him out of camera view. Once back on live TV, Cronkite matter-of-factly described what had happened without an iota of irritation. “Well,” the anchorman said, “a rather interesting development in the studio here — a protest demonstration right in the middle of the CBS News studio.” He told viewers, “The young man identified as a member of something called Gay Raiders, an organization protesting alleged defamation of homosexuals on entertainment programs.”

Segal had a legitimate complaint. Television — both news and entertainment divisions — treated gay people as pariahs, lepers from Sodom and Gomorrah. It stereotyped them as suicidal nut jobs, flaming fairies and psychopathic villains. Part of the Gay Raiders’ strategy was to bring public attention to the Big Three networks’ discrimination policies. What better way to garner publicity for the cause than waving a banner on the “CBS Evening News”? “So I did it,” Segal recalled. “The police were called, and I was taken to a holding tank.”

But both Segal and Langhorne were charged with second-degree criminal trespassing as a result of their disruption of the “CBS Evening News.” It turned out that Segal had previously raided “The Tonight Show,” the “Today” show and “The Mike Douglas Show.” At Segal’s trial on April 23, 1974, Cronkite, who had accepted a subpoena, took his place on the witness stand. CBS lawyers objected each time Segal’s attorney asked the anchorman a question. When the court recessed to cue up a tape of Segal’s disruption of the “Evening News,” Segal felt a tap on his back — it was Cronkite, holding a fresh pad of yellow-lined paper, ready to take notes with a sharp pencil.

“Why,” Cronkite asked the activist with genuine curiosity, “did you do that?”

“Your news program censors,” Segal pleaded. “If I can prove it, would you do something to change it?” Segal went on to rattle off three specific examples of “CBS Evening News” censorship, including a CBS report on the second rejection of a New York City Council gay-rights bill.

“Yes,” Cronkite said. “I wrote that story myself.”

“Well, why haven’t you reported on the other 23 cities that have passed gay-rights bills?” Segal asked. “Why do you cover 5,000 women walking down Fifth Avenue in New York City when they proclaim International Women’s Day on the network news, and you don’t cover 50,000 gays and lesbians walking down that same avenue proclaiming Gay Pride Day? That’s censorship.”

Segal’s argument impressed Cronkite. The logic was difficult to deny. Why hadn’t CBS News covered the Gay Pride parade? Was it indeed being homophobic? Why had the network largely avoided coverage of the Stonewall riots of 1969? At the end of the trial, Segal was fined $450, deeming the penalty “the happiest check I ever wrote.” Not only did the activist receive considerable media attention, but Cronkite asked to meet privately with him to better understand how CBS might cover gay pride events. Cronkite, moreover, even went so far as to introduce Segal as a “constructive viewer” to top brass at CBS. It had a telling effect. “Walter Cronkite was my friend and mentor,” Segal recalled. “After that incident, CBS News agreed to look into the ‘possibility’ that they were censoring or had a bias in reporting news. Walter showed a map on the ‘Evening News’ of the U.S. and pointed out cities that had passed gay-rights legislation. Network news was never the same after that.”

Before long, Cronkite ran gay-rights segments on the CBS News broadcast with almost drumbeat regularity. “Part of the new morality of the ’60s and ’70s is a new attitude toward homosexuality,” he told millions of viewers. “The homosexual men and women have organized to fight for acceptance and respectability. They’ve succeeded in winning equal rights under the law in many communities. But in the nation’s biggest city, the fight goes on.”

Not only did Cronkite speak out about gay rights, but he also became a reliable friend to the LGBTQ community. To gays, he was the counterweight to Anita Bryant, a leading gay-rights opponent in the 1970s; he was a heterosexual willing to grant homosexuals their liberties. During the 1980s, Cronkite criticized the Reagan administration for its handling of the HIV/AIDS epidemic and later criticized President Clinton’s “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy regarding gays in the military. When Cronkite did an eight-part TV documentary about his storied CBS career — “Cronkite Remembers” — he boasted about being a champion of LGBTQ issues. And he ended up hosting a huge AIDS benefit in Philadelphia organized by Segal, with singer Elton John as headliner.

Mark Segal, PGN publisher, is the nation’s most-award-winning commentator in LGBT media. He can be reached at [email protected].