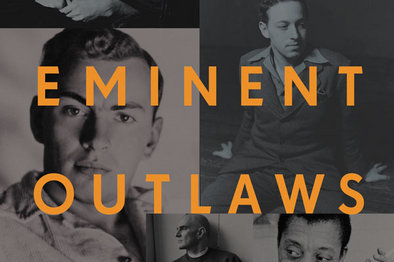

Christopher Bram’s new nonfiction book, “Eminent Outlaws,” is a fantastic history of American gay-male writers and their literature. And Bram is as good a writer as the many folks he includes here. His engaging storytelling captures the essence of what make these bold, pioneering writers essential to our literary canon.

From poet Allen Ginsberg to playwright Tennessee Williams to novelists James Baldwin, Truman Capote, Gore Vidal and Edmund White, among many others, he provides a remarkable chronicle of how gay writing became a catalyst for social change. In a recent email exchange, Bram discussed his book, and the risk-taking writers that inspired him and “Eminent Outlaws.”

PGN: You are primarily known as a novelist, but have published nonfiction essays in the past. What prompted you to write this nonfiction book? CB: I was already thinking about possible nonfiction projects when another writer phoned me and wanted to know the state of gay literature in the 1950s and 1960s. I filled him in for 20 minutes, and I realized no such book existed — and it needed to exist. So I began writing “Eminent Outlaws.” It seemed to be a book I’d been preparing to write for my whole life without knowing it. I read many of the novels and poems I discuss as they came out — or the earlier ones as I came out. I am old enough to remember the antigay press of the 1960s and 1970s, but young [enough] to come out of the experience unscathed. PGN: What did you learn writing the book? CB: Early on, I recognized that the story wasn’t just about my generation — the post-Stonewall generation — but also the generation before, the generation of Capote, Baldwin and Isherwood. The presence of those two generations — fathers and sons, or uncles and nephews, if you will — really excited me. The story is so interesting, and necessary, that I’m surprised nobody has told it before. I assume other gay writers hesitated for the same reason I hesitated: We want somebody else to write about us. But it’s hard to walk away from a great story. PGN: What were your criteria for identifying an author as an “outlaw” or “pioneer”? CB: It’s not an inclusive book and was never intended as such. I had no criteria for whom I included and whom I didn’t. I just concentrated on a handful of writers that best enabled me to tell the larger story — which often meant writers who meant the most to me. Afterward, I went back and wove in some of the writers who didn’t come up naturally — John Rechy, Lanford Wilson, David Leavitt and others.

PGN: Risk seems to be a unifying theme in “Eminent Outlaws,” as well as in your own fiction. Why is this such a critical component to gay writing? CB: I think risk is an important component to all good fiction writing, and not just gay writing. Good writers stick their necks out and take chances. They write what they need to write — what they burn to write — without thinking too much of the consequences. Almost all of the writers I discuss began their careers by writing something gay, got kicked in the teeth, then tried to play it cool, but later came back to the subject. Some were quite cagey about it, such as Gore Vidal, who avoided it after “City and the Pillar,” then returned with “Myra Breckinridge,” recognizing he had hit upon something so polymorphous-perverse it left the idea of “gay” in the dust. Others, like Christopher Isherwood, swore off the subject after being slammed by the critics, tried to write something straight and then said, “Fuck it” and wrote “A Single Man.”

PGN: Do you feel that gay men of letters today continue to create work that is challenging as it was when James Baldwin, Allen Ginsberg and Tennessee Williams first burst on the scene? How has gay writing changed — and is it for the better? CB: They do, but readers are more experienced — more jaded, maybe — and more difficult to shock or challenge. Baldwin’s “Another Country” was a bestseller in the ’60s because it included straight and gay and interracial sex scenes. Readers complained, but they still bought the book — they clearly enjoyed reading those scenes. People don’t read books for sex scenes anymore — they get their porn elsewhere — but challenging, exciting work is done in other areas.

PGN: You deliberately decided not to include yourself in your book, but how has your own fiction transformed over the years in terms of the stories you create and issues you explore in your work? CB: I started with a very self-oriented novel, “Surprising Myself,” that wasn’t autobiographical, but was about all the issues that concerned me personally at the time: coming out, finding love, making peace with my family. But in everything I wrote since, I tried to get beyond that, to explore a wider world. It was always from a gay perspective, but I wanted to take in as much new life as I could. Freeing me to do that, enabling me to explore other areas, was the fact that there were all these other gay writers writing their own novels. None of us needed to worry about doing Gay Life 101 anymore — if there is such a thing.

— Gary Kramer

Edmund White and Christopher Bram will read from their books 7:30 p.m. Feb. 16 at the Free Library of Philadelphia, 1901 Vine St. Admission is free.