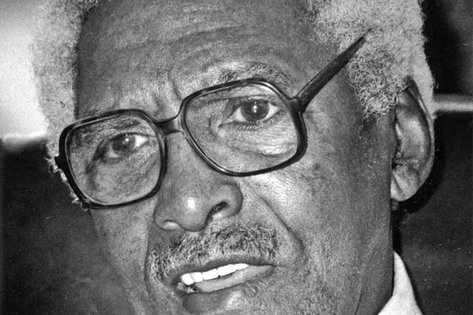

Earlier this month, the world honored the life of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. — a leader whose legacy was impacted by the ideas and influence of an openly gay activist, who next month will receive his own well-earned tribute.

The Chester County Historical Society will launch “Bayard Rustin’s Local Roots,” a retrospective exhibit that looks at the life and works of the openly gay pioneer, tracing his journey from West Chester to the height of the civil-rights movement where he was an organizer, activist and advisor to King.

Rustin died in 1987 but would have turned 100 this year, an occasion that precipitated the hometown exhibit.

Walter Naegle, Rustin’s partner in the last 10 years of his life, said Rustin’s activists spirit took root during his years in West Chester, where he was raised by his grandparents.

“His grandmother was very active in the local NAACP [National Association for the Advancement of Colored People] and she was raised in a Quaker household with a great sense of the value of equal opportunity and nonviolence,” Naegle said. “All of that combined to make her a local social-justice activist in West Chester and she passed that along to Bayard.”

Rustin felt the effects of inequality from an early age, Naegle said.

Rusin’s elementary school was segregated by race and, while his high school was integrated, he still faced racial discrimination.

“Even though West Chester was not in the South, it was a town with a lot of mixed messages,” Naegle said. “He was a very popular student — very smart and athletic — but there were times when he’d be traveling with one of the athletic teams and he couldn’t stay in the same hotel as the other students or he couldn’t sit in the same part of the movie theater when they went out. Even though segregation wasn’t on the books as law in West Chester, there was a history of this customary sense of how people were supposed to behave.”

Rustin resisted those societal limitations, however.

After high school, he went on to study at a number of universities and honed his activist skills — organizing sit-ins and protests against racial discrimination, as well as for pacifist causes. He spent two years in the 1940s incarcerated for violating the Selective Service Act.

Rustin studied with followers of Ghandi during a trip to India in the ’40s, an experience that allowed him to explore ideas on nonviolent resistance.

Those lessons became integral, Naegle said, when Rustin was enlisted as an advisor to King in the 1950s. Rustin was the driving force behind the need for nonviolence as he and King worked together to plan demonstrations such as the bus boycotts in Alabama.

“A lot of that grew out of his studies and his grassroots organizing in the ’30s and ’40s,” Naegle said. “He had organized sit-ins on buses and trains in an attempt to integrate segregated cars and sit-ins in restaurants, hotels, theaters. He was part of a small band of radical nonviolent direct-action activists and was able to bring that knowledge and those experiences back when Montgomery started happening. He helped King to translate the ideas of Ghandi and his civil disobedience into an Americanized version for the Southern United States.”

Rustin was the strategist and main organizer of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963 — during which King delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech — an action that propelled Rustin into the national spotlight, landing him on the cover of Life magazine.

While he received some national attention for his work on the march, Rustin largely worked behind the scenes of the movement, a position Naegle said he was relegated to in part because of his openness about his orientation.

“It happened because of the ‘baggage’ he had: being gay, a former member of the Communist League and a conscientious objector. People considered them to be strikes against him,” Naegle said.

Naegle said Rustin did not broadcast the fact that he was gay, that he but also did not lie if asked.

He noted Rustin did not date women or get married, as some other gay men of the time did in order to better assimilate into society.

“He never hid the fact that he was gay,” he said. “Before the civil-rights movement took hold, it wasn’t really the kind of thing that was discussed and he was more comfortable talking about it publicly during the last 10 years of his life, during the time I knew him. But anyone who knew him or worked with him knew he was gay, knew his friends and his boyfriends.”

While King did not take a firm stance on LGBT rights, Naegle surmised that, if he were alive today, he would be a supporter of the community.

“He believed in the equality of all people and believed that the United States is a democracy that guarantees equal rights under the Constitution, so I think he would be supportive of any rights being extended to gays that are extended to anyone else, including the right to marry,” he said.

Naegle met Rustin in 1977 and the pair spent Rustin’s last decade together.

By that time, Naegle said Rustin had accepted the fact that his name was not as recognizable as King’s.

“He was disappointed that he didn’t get credit for some of the work that he did and the demonstrations he organized, but I think he made his peace with it and was comfortable with it,” Naegle said. “The work was the most important thing to him. It wasn’t about establishing a public position for himself or to satisfy his ambition or ego — he cared about building a community and a movement.”

Perhaps Rustin never sought recognition, but he will receive it in the upcoming exhibit at the Chester County Historical Society, which seeks to educate younger generations about the myriad contributions of the oft-unsung hometown hero.

Ellen Endslow, director of collections/curator at the society, said the organization saw Rustin’s centennial as an opportunity to celebrate his life and the lessons that can be gleaned from his work.

“We try to feature people from Chester County who have done things that have not only helped to influence local people but also the nation, and what other person could have made such a big influence on the nation than him?” Endslow posed. “The concept of equal opportunity is critical and sometimes you need to go the extra mile to make your point, and that’s what he did. When a person believes in something, they need to stand up for that, and I think that’s the most important thing we can learn from him.”

Endslow noted that, unlike some collections that highlight artwork or other materials, this exhibit will primarily focus on Rustin’s ideas and thus will showcase original documents, manuscripts and a number of personal photos and correspondence, some of which Naegle contributed.

To fuel conversation among visitors, the exhibit will also feature a comment book asking guests what, if any, causes they would be willing to sacrifice for — to the point of arrest and incarceration.

While the exhibit is a welcome tribute to Rustin’s life, its display should also illustrate to visitors the value of local-level activism — and the importance of authenticity in changing hearts and minds.

“I think people, especially gay people, who grow up in small towns, can’t wait to get out and go to a city where they feel more comfortable, but it’s important for people to start getting involved and making a difference at home. That’s where Bayard got his start, right in West Chester,” Naegle said. “One of the most important things he used to say is that prejudice and bigotry largely come from ignorance and fear. People aren’t acquainted with other people or have certain notions about other people because they don’t have experience with that community. If he were alive today, he would urge gay people to come out of the closet and be open, be themselves and let their family members and friends know and understand who they are. That’s the best way to change ignorant, bigoted ideas people have about the gay community.”

“Bayard Rustin’s Local Roots” will open Feb. 2 at the Chester County Historical Society, 225 N. High St. in West Chester, and run through August. The exhibit will be open from 9:30 a.m.-4:30 p.m. Wednesday-Saturday and is free with general admission. A reception will be held in early March to mark Rustin’s 100th birthday. For more information, visit www.chestercohistorical.org.