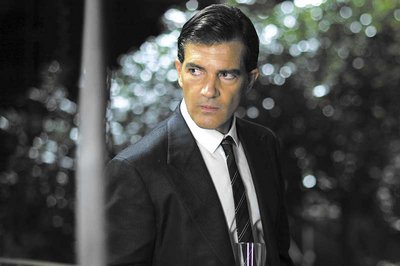

In “The Skin I Live In,” opening at Ritz Theatres today, out filmmaker Pedro Almodóvar reteams with actor Antonio Banderas for the first time in 20-plus years. As a plastic surgeon named Robert Ledgard — who keeps Vera (Elena Anaya) prisoner in his isolated house — Banderas plays another mentally unhinged Almodóvar character. (See also “Law of Desire,” “Matador” and “Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down!”) But while Almodóvar provides his typical over-the-top flourishes as a filmmaker, and Banderas exudes a cool, sinister calm as the mad-as-a-hatter doctor, “The Skin I Live In” is an ugly, unpleasant film. Almodóvar punishes his characters — and viewers — by having the females raped, kidnapped and held hostage/imprisoned; the women are also in some cases insane, suicidal and murderous. None of them ever emerge as real human beings.

For a filmmaker who has often been described as a “woman’s director,” the Spanish bad boy seems to denigrate women as much as he supposedly loves them. To be fair, the two main male characters are both crazy, as well as thieves, kidnappers/hostage takers and murderers. At least Almodóvar is an equal-opportunity offender.

“The Skin I Live In” opens in Toledo in 2012. Ledgard is experimenting with “transgenesis,” a radical — and illegal — artificial skin-graft treatment. Vera, his unwilling “patient,” is being kept captive in secret until a stranger, Fulgencio (Eduard Fernández), arrives. Fulgencio, in typical Almodóvarian plotting, is a jewel thief on the lam from police. He arrived in an animal costume disguise. Fulgencio wants to hide from the authorities who are on his tail (the tip of which comically resembles the head of a penis). Unbeknownst to him, however, Vera is already in hiding. When Fulgencio discovers this, he rapes her. It is one of the two rapes that set the story in motion.

The other violation, as the film shows in an extended flashback sequence that takes place six years prior, involves Robert’s daughter, Norma (Blanca Suárez). She is an insecure young girl who is raped by Vincente (Jan Cornet) at a party. The consequences of this act lead to a series of plot twists that connect the characters and storylines in ways that should not be revealed.

While Almodóvar lets “The Skin I Live In” unfold with his standard approach: curlicue plotting, vivid colors, striking camerawork and composition, the film is disappointing because the intricate plotting never satisfies. Fulgencio has a connection to Robert that is underdeveloped to the point of being unnecessary. It is a red herring. As Vera’s role in the story becomes clear, her character’s motivation makes sense, but knowing this drains the story of its dramatic tension and forcefulness. Had this reveal been a surprise — rather than telegraphed so early on — the film could have wowed audiences.

Even when a female character does get the upper hand, the revenge element seems uninspired. Almodóvar’s outrageousness needs to extend beyond his storytelling and shock value. The filmmaker appears to be all too impressed with himself, and he wants to extend that feeling to his diehard fans.

Where “The Skin I Live In” does excel is in its commentaries about literally putting one’s own fingerprint on another human. From an identifying birthmark on Fulgencio’s ass to treating the skin of a burn victim and a character undergoing a sex change, the film examines the multiple layers of how bodies are used, abused and recycled. Vera is kept in a bodysuit that makes her look like a blank canvas. The marks on her skin represent her wounds, both visible and invisible. But they never seem anything other than superficial. And the way Robert spies on her nakedness with a large video screen in his bedroom is voyeurism at its creepiest.

These images and moments are striking, but they only scratch the surface of what Almodóvar may be trying to say about the way people graph their lives on others, or how individuals need to be comfortable with who they are/in their own skin. The idea of taking responsibility for one’s actions is played for darkly comic effect, making it less potent a message than it could be.

Ultimately, “The Skin I Live In” is just skin deep.