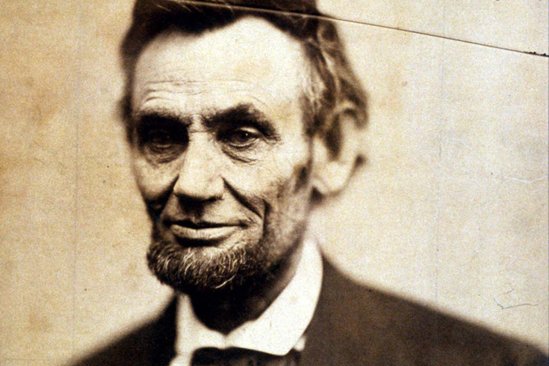

Abraham Lincoln (1809-65) may likely be the most studied and researched of the United States presidents. The first reference to him possibly being “homosexual” came from notable Lincoln expert Carl Sandburg in his 1926 biography, “Abraham Lincoln: The War Years.” In describing the early relationship between Lincoln and his close friend, Joshua Fry Speed, Sandburg wrote “a streak of lavender, and spots soft as May violets.” This line got historians talking about an issue from which many had previously shied away.

Still, the biography was written in the early 20th century, a time when such topics were only discussed in whispers. But by including the line, Sandburg felt the relationship deserved acknowledgement. It wasn’t until 2005 when the first book was published on Lincoln’s relationships with men, C.A. Tripp’s “The Intimate World of Abraham Lincoln.”

Detractors of Lincoln’s possible homosexuality, such as historian David Herbert Donald, often say there is no new evidence on Lincoln. Yet historians continue to draw fresh conclusions from Lincoln’s letters. Those who attempt to refute Lincoln’s possible “homosexuality” usually focus on one particular incident — of the many — that supports the theory: his relationship with Speed.

Yet history, like everything else, is open to interpretation and influenced by new findings. Bias also motivated the retelling of historical events. The best example of bias in American history is the story of Thomas Jefferson and his slave/concubine Sally Hemings, which was not accepted as a truthful account until 1998 — and only after DNA proof. African-American citizens — not historians — led the effort to give Hemings her rightful place in history. Likewise with Lincoln, most historians have referred to isolated facts rather than the pattern of events in his life to tell his personal story. Will history once again prove historians wrong?

THE POEM I will tell you a Joke about Jewel and Mary It is neither a Joke nor a Story For Rubin and Charles has married two girls But Billy has married a boy The girlies he had tried on every Side But none could he get to agree All was in vain he went home again And since that is married to Natty So Billy and Natty agreed very well And mama’s well pleased at the match The egg it is laid but Natty’s afraid The Shell is So Soft that it never will hatch But Betsy she said you Cursed bald head My Suitor you never Can be Beside your low crotch proclaims you a botch And that never Can answer for me

This poem, about a boy marrying a boy, is thought to be the first reference to gay marriage in U.S. history. A 20-year-old man in rural Indiana wrote it 182 years ago. That young man was Abraham Lincoln. Most historians agree Lincoln wrote the poem as a joke or rebuttal to the lack of an invitation to a friend’s wedding, but how a backwoodsman conceives a boy-marries-boy poem in 1829 remains a question.

The poem was included in the first major biography of Lincoln, written by his law partner, William Herndon. Revisionists omitted it in subsequent editions. It didn’t reappear in Herndon’s edition until the 1940s.

BILLY GREENE

In 1830, when Lincoln’s family moved to Coles County, Ill., he headed out on his own. At age 22, he settled in New Salem, Ill., where he met Billy Greene — and, as Greene told Herndon, the two “shared a narrow bed. When one turned over the other had to do likewise.” Greene was so close to Lincoln at that time that he could describe Lincoln’s physique. However, Lincoln was poor at the time and it was not unusual for men in poverty to share a bed.

JOSHUA FRY SPEED

In 1837, Lincoln moved to Springfield, Ill., to practice law and enter politics. That’s where he met the two men who would be his greatest friends throughout his life. One, Joshua Fry Speed, became his bed partner for a while; the other was law partner Herndon. Beyond the revelation that Lincoln and Speed had an intimate friendship, little has been written about how diligently Speed worked for Lincoln’s legal and political career. Speed’s name popped up in many of Lincoln’s legal filings and on the Illinois Whig Party’s central committee. The two were almost inseparable. Most Lincoln historians agree this relationship was the strongest and most intimate of the president’s life. What they don’t agree on is why they slept in the same bed together for four years when they had the space and means to sleep separately, as was expected of men their age. They were no longer young and poor. And this was a house with ample room, unlike the hotels that accommodated Lincoln and his team on the road; then, it was common to sleep two or more in a bed.

By 1840, both Lincoln and Speed — now 31 and 26— were considered well past the marrying age. Both bachelors reportedly were hesitant to tie the knot, but it was a de-facto requirement to have a wife if you wanted to move in political circles — or at least create the perception of interest in marriage. Both Speed and Lincoln dreaded this “requirement,” as evidenced by Lincoln’s letters. Speed takes the marriage plunge first and moves back to Kentucky, leaving Lincoln. At this precise time, Lincoln suffered a mental breakdown. Historians have been all over the map as to what caused the breakdown, but it was so intense that friends, including Herndon, worried he would take his own life. Lincoln only recovered after Speed invited him to visit him and his new wife in Kentucky.

Lincoln’s most emotional and intimate writings were contained in his letters to Speed. From the time they lived together until shortly after Speed married and moved to Kentucky, Lincoln always signed his letters “forever yours” or “yours forever.”

Lincoln wrote to Speed shortly before the latter’s Feb. 15, 1842 wedding: “When this shall reach you, you will have been Fanny’s husband several days. You know my desire to befriend you is everlasting — that I will never cease, while I know how to do any thing.

“But you will always hereafter, be on ground that I have never occupied, and consequently, if advice were needed, I might advise wrong.

“ … I am now fully convinced, that you love her as ardently as you are capable of loving … If you went through the ceremony calmly, or even with sufficient composure not to excite alarm in any present, you are safe, beyond question, and in two or three months, to say the most, will be the happiest of men.

“I hope with tolerable confidence, that this letter is a plaster for a place that is no longer sore. God grant it may be so. “I would desire you to give my particular respects to Fanny, but perhaps you will not wish her to know you have received this, lest she should desire to see it. Make her write me an answer to my last letter to her at any rate. I would set great value upon another letter from her. “P.S. I have been quite a man ever since you left.” The two exchanged letters regularly and, in October 1842, Lincoln observed the newlywed Speed was “happier now than you were the day you married her.” He continued: “Are you now, in feeling as well as judgment, glad you are married as you are? From any body but me, this would be an impudent question not to be tolerated; but I know you will pardon it in me. Please answer it quickly as I feel impatient to know.”

The urgency in his letter is palpable: Lincoln married Mary Todd on Nov. 4, 1842, despite that he broke off their engagement two years earlier.

Even after the Civil War broke out and Speed lived in Kentucky — a border state — Lincoln and Speed continued to write. On numerous occasions, Speed visited Lincoln at the White House; he even spent a night with Lincoln in the president’s cottage at the Soldier’s Home, 3 miles northwest of the White House.

Throughout Lincoln’s political career, he urged Speed to accept a political appointment that would bring him to live in Washington, D.C. When that failed, he appointed Speed’s brother, James, U.S. attorney general in 1864.

ELMER ELLSWORTH

After Speed and Lincoln’s marriages, there were no traces of other men in Lincoln’s life until Elmer Ellsworth in 1860. According to “The Abraham Lincoln Blog,” in 1859, Ellsworth formed the Chicago Zouaves, a precision military drill team based on the famous Zouave soldiers of the French Army based in northern Africa.

The Chicago Zouaves, led by Ellsworth, toured the northern states in the months before the Civil War, with the so-called regiment performing acrobatic moves, marching and weapons displays. The regiment impressed the crowds — despite the fact that they’d never seen military action.

Lincoln met Ellsworth through these displays and the two became friends. Lincoln invited Ellsworth, who had been a law clerk in Chicago, to move to Springfield to study law. Ellsworth became devoted to Lincoln and adored by the entire Lincoln family. One author wrote that it seemed Lincoln had a “schoolboy crush” on the much-younger Ellsworth. He first worked in Lincoln’s law practice, then moved on to his political career and eventual campaign for president. Once elected, Lincoln asked Ellsworth to accompany his family to Washington.

At the beginning of the Civil War, Ellsworth asked Lincoln to assist in obtaining a position for him in the Union Army. In a letter dated April 15, 1861, Lincoln wrote: “I have been, and still am anxious for you to have the best position in the military which can be given you.”

When a call for soldiers went out, Ellsworth headed to New York and rallied 1,000 men, then returned to Washington, D.C. When Virginia voted to secede on May 23, 1861, a hotel owner in Alexandria, Va., across the Potomac River, raised a Confederate flag — visible from Lincoln’s office. Early the next morning, Ellsworth and his men crossed the river and occupied the telegraph office to cut off communications. Seeing that the hotel was next door, Ellsworth entered it and took down the flag, then was fatally shot by the hotel’s proprietor. Ellsworth would be the first Union soldier killed in the war.

After hearing of the tragedy, Lincoln wept openly and went with Mrs. Lincoln to view the soldier’s body. Lincoln arranged for Ellsworth to lay in state in the White House, followed by a funeral. The president was inconsolable for days.

Lincoln wrote condolences to Ellsworth’s parents: “My acquaintance with him began less than two years ago; yet through the latter half of the intervening period, it was as intimate as the disparity of our ages, and my engrossing engagements, would permit … What was conclusive of his good heart, he never forgot his parents.”

As with Speed and his family, Lincoln appointed Ellsworth family members to positions in the government.

DAVID DERICKSON

In 1862, Lincoln met Capt. David Derickson, who served as his bodyguard, providing protection for the president when he commuted from the White House to his cottage at the Soldier’s Home. Lincoln spent about a quarter of his presidency at the cottage, which allowed him some escape from D.C.’s summers and from public interruptions at the White House.

Lincoln and his bodyguard became close, and historians Tripp and David Herbert Donald noted two recorded mentions that Lincoln and Derickson slept in the same bed: Derickson’s superior, Lt. Col. Thomas Chamberlain, and Tish Fox, the wife of Assistant Navy Secretary Gustavus Fox, both wrote about it. Tish wrote in her diary that Derickson was devoted to Lincoln and “when Mrs. Lincoln was away, they slept together.”

But there were more than just two eyewitnesses to this relationship. After the war, Chamberlain published an account of the regiment called “History of the 150th Regiment of Pennsylvania Volunteers, Second Regiment, Bucktail Brigade.” Before it was published, many members of the company reviewed the manuscript and no one objected to the following:

“[Lincoln] was not long in placing the officers in his two companies at their ease in his presence, and Capts. Derickson and Crozier were shortly on a footing of such marked friendship with him that they were often summoned to dinner or breakfast at the presidential board. Capt. Derickson, in particular, advanced so far in the president’s confidence and esteem that in Mrs. Lincoln’s absence he frequently spent the night at his cottage, sleeping in the same bed with him, and — it is said — making use of his excellency’s nightshirt! Thus began an intimacy which continued unbroken until the following spring … ”

The Bucktails witnessed the relationship between the president and his bodyguard, which was public enough that they knew Derickson kept him company when Mrs. Lincoln traveled, and wore his nightshirt. Historical interpretations aside, why would the president, then in his 50s, sleep with his bodyguard?

DETRACTORS

The most outspoken and respected of detractors is historian and Lincoln biographer David Herbert Donald, arguably the most notable Lincoln observer since Sandburg. In his attempts to refute Lincoln’s possible homosexuality, Donald claims in his book “Lincoln’s Men” (2004) that while Speed and Lincoln slept together for four years in the same bed, they both were romancing women during two of those years. But the fact that he courted women doesn’t rule out the possibility that Lincoln may have preferred men. Donald also noted that no contemporaries of the two, including Herndon, claimed to have witnessed Speed and Lincoln having intimate relations. But Donald ignored eyewitness accounts and misinterpreted other witnesses who hinted at it, such as the president’s own secretaries. The historian also brushed aside the emotion contained in the letters between Lincoln and Speed, in their own handwriting. Donald pointed out it was common for 19th-century young men to have emotional relationships and share a bed. But Speed and Lincoln weren’t considered “young” when they met.

Doris Kearns Goodwin, in an interview on C-SPAN about her 2006 Lincoln biography “Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln,” said, “Homosexuals didn’t exist before the word was coined in 1868 … ” She most likely meant the term didn’t exist, but this clearly demonstrates a lack of sensitivity by non-gay historians. Goodwin has to be familiar with Lincoln contemporary Walt Whitman. While the words “homosexual” and “gay” were not coined at that point, Whitman now is considered to have been gay.

Younger historians and Lincoln scholars seem to be more sensitive to the subject than Donald or Kerns were. For example, Jean H. Baker, a former student of Donald, conceded in her acclaimed 1987 book, “Mary Todd Lincoln: A Biography,” that Lincoln’s distraction from his wife was likely due to more than just his all-consuming work. Baker said, in a New York Times interview, “I previously thought [Lincoln] was detached because he was thinking great things about court cases … now I see there is another explanation.”

CONCLUSIONS

Taken individually, accounts of Lincoln with other men may not offer enough proof that he was gay. But the pattern reveals a man who, in his sexual prime, slept exclusively with another man for four years — two of those years (according to Donald) without romancing someone of the opposite sex; who wrote a poem about a boy marrying a boy; and who, as president, slept with his bodyguard.

From historical records, one can conclude that Lincoln enjoyed sleeping with men. He did so when it was acceptable in youth and poverty, and also when he was older and successful. While it is documented that Lincoln slept with several men, there is only one confirmed woman who shared his bed — Todd.

Mark Segal is founder and publisher of Philadelphia Gay News. Sometimes called the Dean of the Gay Press, the award-winning columnist is fascinated by history.