During National Hispanic Heritage Month, we decided to spotlight someone we had the pleasure of honoring with a Lambda Award back in February 2000.

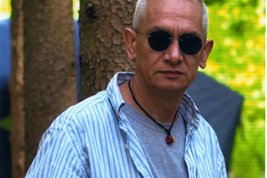

I would list all of the accolades, honors and positions David Acosta has held, but there wouldn’t be any space left for the interview. Let’s leave it that the poet, activist and civil-rights proponent recently won the Revolutionary Leader Award for his years of service to the community, and you can Google him when you have a few free hours for the full list of his accomplishments. We pulled him from his busy schedule for a quick chat.

PGN: Hey David, what’s new? DA: I’m excited by my most recent project, “Witness.” We’re working with 22 artists who are doing work responding to 30 years of the AIDS pandemic. It’s a multimedia visual-arts exhibition inviting artists to reflect on, explore and respond to the impact the HIV/AIDS epidemic has had on our social, cultural and political life over the past 30 years. It’s great because the artists selected reflect a diverse gathering of voices across, race, age, gender, sexual orientation and geographic location. The art itself showcased in “Witness” asks us as an audience to reflect individually and collectively on the HIV/AIDS epidemic as a transformative moment in our lives. Thirty years later, “Witness” calls on artists to reengage themselves and their communities in remembering, honoring and imagining a world in which AIDS has transformed our past, impacts our present and continues to shape our future.

PGN: That sounds like it’s going to be an amazing show. When is it opening? DA: It opens on first Friday, Dec. 2, at The Asian Arts Initiative, 1291 Vine St., and runs through Jan. 27, 2012.

PGN: So tell me about yourself. Where were you born? DA: I was born in Cali, Colombia, South America. I moved to the States in the late ’60s with my family when I was about 10, and have lived in Philly the entire time with the exception of a two-year stint in New Orleans.

PGN: What fond memories do you have about Colombia? DA: I remember quite a lot; I have a lot of family still there, as well as those living here. My best memory would have to be staying with my grandparents. I spent an incredible amount of time with them. I’d go for a visit and end up spending weeks at a time with them, sometimes months. They were in the same city as my family, so I’d see my parents the whole time but stay with the grandparents. They were also my godparents, which in Columbia is a very big deal. It’s a serious business and not taken lightly.

PGN: What did you do with your grandparents? DA: My grandfather had a strong interest in birds, so I would help him with his aviary, and my grandmother loved to garden and let me help her with that. I was always underfoot or following them around and they ensured that I got to go everywhere with them. They were all fond memories.

PGN: What did your parents do? DA: My father was a mechanic and my mother was a stay-at-home mom.

PGN: Did you pick up any mechanical skills from your dad? DA: [Laughs.] Absolutely not! No, not at all, not in the least, no! I can’t put two and two together! He, on the other hand, could rig anything together and make it work.

PGN: Any siblings? DA: Two: an older brother and younger sister. I’m in the middle. Some would say I suffer from middle-child syndrome, but it’s not true.

PGN: I’m a middle child too, but we were all in the spotlight: The eldest was the first boy and a star athlete, I was the only girl, and even though we’re adults now, my younger brother is still the baby. So we all had our moment. DA: Oh no, in my family my sister got doted on as the only girl, my brother got doted on as the first boy and I was kind of, well … my parents loved me, but I was just there — the middle child.

PGN: What was a favorite thing to do as a kid? DA: I had some aunts that were younger than me, my mother’s sisters, that I liked to play with but I also enjoyed being by myself a lot. I made up games in my head. And as I said, being with my grandparents was fun. They inhabited an adult universe that I could gain access to through them. I was around a lot of older people who paid a lot of attention to me. They always included me in the adult conversation circles. I was very comfortable around grown-ups and I was extremely precocious so I would sit and entertain the adults, tell them stories and such. I would visit neighbors’ houses and they would give me food and special treats. I could have had lunch four or five times a day if I wanted! I had a vivid imagination so they enjoyed my company.

PGN: What was an early sign that you were gay? DA: I think I’ve always known. I didn’t know what it was, I couldn’t name it, but back as far as 3 years old, I knew I was different. The world mirrors something back at you that lets you know that something about you is not the norm. When I was 5 or 6, I realized that I felt different about boys than I did girls — physically, mentally, emotionally. It’s funny: We don’t want to think of children as gay because people don’t want to sexualize them, but I knew how I felt even at that age.

PGN: It seems that many countries in South America are surprisingly gay-friendly, considering the machismo stereotype. DA: Yes, it’s an interesting place. In the last 20 years, there’s been a lot of movement toward acceptance. There are a number of places — Mexico City and Argentina — that have passed gay marriage, and same-sex civil unions are legal in Uruguay, Ecuador, Brazil and Colombia. If you visit, there are huge gay meccas with large gay communities with shopping and restaurants and huge Pride celebrations. There’s homophobia too of course, but there’s also a high level of acceptance. As you said, it’s not as homophobic as people expect, given the macho-male reputation. It’s not really any different than the U.S. The Catholic Church does play a role, but most people choose which doctrines they want to abide by and ignore the rest.

PGN: When you moved to the States, what was the biggest culture shock? DA: Well, leaving family behind was difficult. My mother’s family had been coming here on and off since the ’20s, either to go to school or for business purposes, but we were the first to settle here. It was different getting used to the way the houses looked, but the hardest thing was getting used to the cold. We came from a country where it was summer 365 days a year. The first snowfall we ever saw was thrilling though: We played outside in it for hours. It was quite a novelty.

PGN: Where did you go to school? DA: I graduated from Temple as an English lit major. Then I went to New Orleans for my sister’s wedding and loved it. I lived there for two years.

PGN: What was your first job? DA: Waiting tables in New Orleans.

PGN: And what’s your job now? DA: I’m the prevention coordinator for HIV programs at AACO [AIDS Activities Coordinating Office], which is a part of the Philadelphia Department of Public Health.

PGN: How did you become an activist? DA: I was involved in my teens. I was involved with some Native American causes like forced relocation at Big Mountain and other stuff. I also got involved in the nuclear disarmament movement and Three Mile Island, so I’ve been somewhat involved since I was young. But I became much more active in the mid-’80s when I was appointed to the Mayor’s Commission on Sexual Minorities. That gave me a lot more access and allowed me to question what services were out there and what needed to be done. That’s when I started GALAEI.

PGN: What does GALAEI stand for? DA: Gays and Lesbian Latino AIDS Education Initiative.

PGN: Oops, I only spelled it with one “l.” DA: Well, in the Spanish alphabet there’s a letter with a double-l, but using it would make the name sound like a rooster, so we opted to just use one “l.”

PGN: I see you’ve been involved in so many things: ACT-UP, AIDS Law Project, Prevention Point, Philadelphia Working Fund for Artists with HIV/AIDS, Midnight Cowboy, Asian Arts Initiative, you’re a founding member of Temple University’s literary journal and you founded the National Campaign for Freedom of Expression. What’s a project or event that really stands out for you? DA: Oh gosh, I guess the early days of ACT-UP when we did demonstrations in front of the Bellevue Stratford when Bush came to Philly, that one made national headlines. Organizing the first Day Without Art, World AIDS Day observances, the first day we showed up to distribute syringes in Kensington stands out. We knew we were breaking the law and could have been arrested at any point.

PGN: You’re a poet and writer: Name a favorite author. DA: That’s difficult because I have such a voracious appetite for literature and poetry. I read a lot and very widely, especially if I can get it in Spanish, plus I often reread authors, so it may depend on what time of my life I’m reading them. I’m currently reading Philip Levine, who was named Poet Laureate of the United States, so he’s a fav. I’m rereading his entire works and enjoying some of the pieces as much now as I did 30 years ago when I first read them. He writes a lot about the working class and steel cities and the Depression, and there’s a lot that he wrote that mirrors some of what is going on now. There’s a poetic resonance that echoes though it — sad but powerful, the poet as prophet.

PGN: OK, arbitrary questions. If you were on a reality show, which would you choose? DA: Oh dear, I love to travel. So, probably that one where they do the world race. What’s it called?

PGN: [Laughs.] “The Amazing Race.” What’s the background on your computer? DA: Absolutely nothing. I just got a new computer so it’s still blank, but it was a rhino. I love rhinoceroses!

PGN: Household chore you hate most? DA: Vacuuming.

PGN: What’s a trait that you inherited from a parent? DA: I probably have more of my mother’s DNA: I have an obsession with order and cleanliness that I inherited from her.

PGN: Any hobbies other than writing? DA: I like cooking and I like gardening and, as I said, I love to travel.

PGN: What was an exciting travel adventure? DA: When I was backpacking through Mexico, we got stopped at the border between Mexico and Guatemala by guerilla fighters. They took us off the bus and searched us. They eventually let us back on, but it was very scary.

PGN: What’s a hidden talent? DA: I used to be able to sing really well. I was quite the crooner as a child, which was one of the reasons people enjoyed having me around. I was like a jukebox: I had a good memory and knew over 250 songs when I was only 5 or 6. They would offer me a piece of cake or candy and I’d sing my little heart out!

PGN: I understand you describe yourself as a feminist; how come? DA: Well, I think that a lot of the work that I’ve done has been informed by feminism: Both queer theory and organizing came out of that. A lot of women have done the work throughout the world for social change and realigning the male-centered paradigm. I’ve worked with a lot of women who’ve been mentors for me. So yes, I feel I’m a feminist.

PGN: What is your full name? DA: Juan Armando David Acosta-Posada. Traditionally, in Latin America, we use our father’s name and our mother’s name.

PGN: Do you have a partner? DA: Yes, Jerry MacDonald. We’ve been together for 17 years.

PGN: What’s the secret to a long partnership? DA: Hmm, not giving up. Learning to compromise by realizing that you can’t always have your way! Keeping the lines of communication open is important. And lots of laughing! You really have to remember to enjoy each other.

PGN: One thing that struck me about you is the wide range of people and causes you’ve championed. A lot of people get stuck in a niche, working only with their own community, but you’ve been a part of everything from Native American groups to being involved with the Asian Arts Initiative to feminist causes. You really seem to be a child of the world. DA: [Laughs.] Wow, what list are you reading from?

PGN: You’re everywhere David! DA: Well, I’m really, really intellectually curious. So for me, part of what I like about community organizing is getting to work with people who are not like you — who may come from different backgrounds and cultures or different experiences — and learning from them. I like to put myself in situations where I have to interact with other communities and learn to be mindful and respectful of how other people do things and how they perceive things. The things you learn from them become really important as you navigate in a bigger world. So yeah, I truly enjoy and embrace diversity. I think it’s important for my view of a just and sane world. And it’s fun!

To suggest a community member for “Family Portrait,” write to portraits05@aol.com.