When HIV and AIDS were first diagnosed 30 years ago, the disease was viewed as a veritable death sentence. Today, with the advances in medical technology, people have lived with the disease for decades — something that was thought of as impossible 20 years ago.

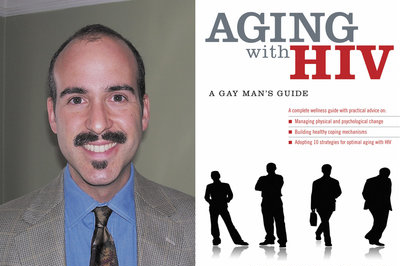

James Masten, Ph.D., a psychotherapist and clinical-research consultant for Yale University, interviewed 15 gay men living with HIV at midlife as the basis for his new book, “Aging with HIV: A Gay Man’s Guide.” In the book, Masten offers guidance about the mostly uncharted territory that individuals living longer with HIV find themselves in.

“What I was responding to was the large and growing population of people who are living with HIV longer than they expected,” Masten said. “By 2015, more than half of the people living with HIV are going to be over age 50. I don’t think as a society we’re prepared for that. I don’t think the public-health system is prepared for that. And I think a lot of people with HIV haven’t anticipated the challenges of growing older. The book is intended to help gay men who have lived longer than they expected to meet the challenges of aging.”

While Masten believes that addressing the physical challenges of living with HIV is equally important, “Aging with HIV” focuses more on the mental aspects.

“Of course there are physical challenges to aging,” he said. “One of the primary physical challenges that I learned from talking to people with HIV, that is also supported by the literature, is the challenge of knowing whether a symptom is HIV-related or age-related. It’s like, ‘Is it AIDS or age?’ We call that symptom ambiguity. A lot of people that are in that group may not realize what a significant problem that poses. Because if you don’t know what’s causing a symptom, then how do you know how to treat it? In some ways, we’re in the same place in the science of HIV that we were two decades ago. We are on the edge of a new frontier. We don’t know what living with HIV for 20 years does to a person. We don’t know what effect taking HIV medications for 20 years has on someone’s immune system or other physical issues. We don’t know how HIV medications interact with other medications. In a way, people living with HIV have to become experts on their own bodies and help guide research in the next decade.”

Masten added that having people in their lives who understand their struggles are beneficial to people living with HIV but, oftentimes, gay men over age 40 don’t have that support.

“Having a good social-support system that you feel is there for you is one of the most significant aspects that encourages healthy aging. The same is true for aging with HIV. All of the research points to having a varied support system, and among those people would be people who understand your experience. That can be a challenge for so many gay men that have lost their entire social-support networks. Many of them have to rebuild communities because their entire friendship networks have been decimated by the disease.”

Even though most stories about HIV/AIDS seemed to be centered on young gay men, Masten said the press is starting to catch on to how HIV continues to affect the generation that it first impacted.

“There is increased interest and attention to people living with HIV over 50,” he said. “The media is starting to realize this. I’m talking primarily about an American and First World phenomenon. In the health system of the Third World, sadly people are not living as long as the First World or don’t have access to the drugs. But for people in the U.S., I think the media is starting to catch on. The White House just did a huge panel presentation on the challenges of aging. I think people are starting to recognize that aging is posing a significant public-health issue for our society in terms of HIV.”

“Aging with HIV: A Gay Man’s Guide” is published by Oxford University Press and is in stores now.

Larry Nichols can be reached at larry@epgn.com.