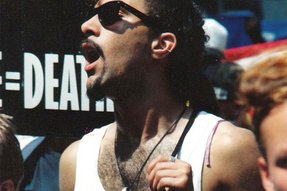

Jon Paul Hammond, a longtime harm-reduction activist and the co-founder of the city’s needle-exchange program, died Nov. 5 of a drug overdose at age 50.

Hammond, a native of Philadelphia, was one of the founders of Prevention Point Philadelphia, which launched in the early 1990s to allow injection-drug users to swap used needles for clean ones in an attempt to reduce the spread of diseases like HIV.

Hammond, who identified as pansexual, was HIV-positive and struggled with drug use for many years.

He grew up in Northern Liberties and attended Friends World College in New York. While at a student conference in college, he met Wende Marshall, who would become his future wife twice.

“He was a wonderful and amazing man, but he was also quite a pain sometimes and we really went through a journey since I was 21,” Marshall said. “But I loved him.”

The two were friends for several years before eventually becoming lovers. After he graduated, Hammond was hired as the student executive of his Quaker-run alma mater. His father died in 1989 and the two moved to Philadelphia, where they lived next door to Hammond’s mother.

Marshall said Hammond became very involved in ACT UP once back in Philadelphia, and worked with the other members to create Prevention Point.

Jose Benitez, current executive director of Prevention Point, said Hammond’s work to get the agency off the ground proved invaluable.

“He was one of the few people who at the early days of the epidemic, when HIV was just running rampant from the IV-drug-using community, stood up and said that we need something like a syringe exchange,” Benitez said. “He was responsible for saving the lives of countless people.”

Hammond was influential in raising awareness among the political world about harm reduction, pressing then-Mayor Rendell to sign the executive order allowing drug users to carry syringes.

Hammond and Marshall married in 1992, but Marshall left him three years later when his drug use became too intense, she said.

Hammond spent time living in California, working with HIV/AIDS activists and researchers in San Francisco on harm-reduction and overdose-prevention efforts From 1994-2001, he served as a board member of the National Harm Reduction Coalition.

Dr. Lauretta Grau, associate research scientist at the Yale School of Public Health, met Hammond in 1997 and said that, while his passion was activism, he was also an exemplary researcher.

“He was on a multi-site project we were doing of active injectors as part of our research field team, and he was a very wonderful, careful, systematic researcher,” he said. “He did a lot of epidemiological research for us and was a wonderful, wonderful colleague. He was reliable, he was fastidious and he was organized. He was an extremely bright man.”

Hammond moved back to Philadelphia in 2005 and last year called Marshall, telling her he believed he wasn’t going to live much longer. The two began spending time together again and remarried Sept. 5, 2009.

“He came back into my life after 14 years, and he had asked me to help him die, but I said, ‘OK, but let’s see if we can figure out how to live.’ So that’s what we did,” she said. “He started taking anti-retrovirals and he bloomed.”

Marshall was teaching at the University of Virginia, but after several months of a long-distance relationship, moved back to Philadelphia this past summer.

She said that although her husband tried hard to keep his drug use under control, its effect on him became more apparent to her once she was living with him again.

Marshall noted Hammond’s drug use stemmed from the same place that fueled his passion for fighting for marginalized communities.

“He was an exquisitely sensitive man who felt the pain of the world very intensely. Some people can notice pain and keep on going, but for him all the pain of the world was felt internally; that wasn’t something he could externalize,” she said. “He wasn’t a saint or anything, he was also a super-big pain in the ass. He just wanted the wretched of the earth to be heard. He thought that the most oppressed should be part of the process and he wanted people accepted without stigma.”

A memorial service was held Nov. 14 at Arch Street Friends Meeting House, where Hammond was an active member.

Marshall said during the service, several people spoke about the enduring nature of Hammond’s work, which she said he worried people would never appreciate.

“One of the last things he said to me was that people can’t recognize his contributions because they’ve been overshadowed by his drug use,” she said. “But at the service, people got up and talked about how many lives he saved. He saved so many lives through his work in San Francisco and then through Prevention Point here in Philadelphia. We’ll never really know just how many people were saved because of him.”

In addition to Marshall, Hammond is survived by mother Rochelle Sinclair Hammond, brother Martyn Luther Hammond, niece Savannah and many other relatives and friends.

Donations can be sent to the Jon Paul Hammond Memorial Fund, c/o The Harm Reduction Coalition, 22 W. 27th St., fifth floor, New York City, NY 10001.

Jen Colletta can be reached at [email protected].