I visited a holy site the other day.

My partner and I were celebrating our 32nd wedding anniversary, and happened to be in San Francisco. We exited the 38R bus at Taylor and walked down to Market Street. Along the way, zig-zagging through temporary barricades shunting people away from ripped up sidewalks — the victim of what looks like some pretty involved infrastructure work — I realized where we were.

The corner of Turk and Taylor streets.

To the uninitiated, this is just another shopworn corner in San Francisco. Many of the structures are a bit worn down after decades of existence, and the sounds of heavy construction and urban traffic added little to the scene.

Across from us was a gray, four-story building, trimmed in blue. The ground floor, featuring hazy, block windows, was vacant. The upper floor boasts transitional housing. Once we had the light, we crossed to this structure, 101 Turk Street.

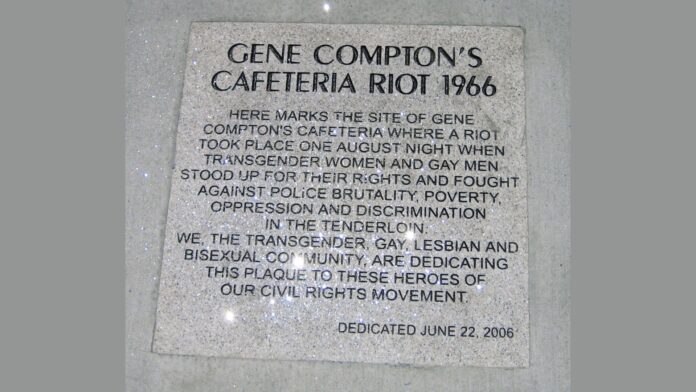

I mentioned the torn-up sidewalks, but one area, on the Turk Street side of the building were two plaques, untouched, inset into the ground. They told the story.

The area where Turk and Taylor sits is the heart of the Tenderloin, and has been known as one of the rougher neighborhoods in the city. Thanks to 1960s “urban renewal” programs elsewhere in the city, the area ended up with a larger than average gay and trans demographic, and a fair amount of sex workers.

In the 1960s, this gray building was the home to Compton’s Cafeteria.

The cafeteria, at the time, was open 24 hours, and ended up being used as a social space for trans people — predominantly trans women — who were involved in the local sex trade. The cafeteria, meanwhile, sought to deter its trans clientele. They added service fees aimed at them, and would harass them in an attempt to get them to move on. They also would often call the San Francisco Police Department. You see, at the time “female impersonation” was a crime.

One August night in 1966, the police were called. An officer grabbed at one trans woman in an attempt to arrest her. She retaliated, throwing a cup of coffee at his face. A riot quickly ensued. It was the first such riot led by trans and queer people fighting for their rights, predating the far more well-known Stonewall Uprising of 1969.

As I said, it is a holy site.

In 2017, just a hair over 50 years after the plate glass windows of Compton’s Cafeteria were broken out, the City of San Francisco recognized Turk and Taylor — and much of the surrounding area, as a transgender Cultural District. The streetlight at Turk and Taylor sports the colors of the transgender flag, and banners of the same hang throughout the area.

The Transgender District is the first legally recognized transgender district in the world and, per their website, is on a mission, “to create an urban environment that fosters the rich history, culture, legacy, and empowerment of transgender people and its deep roots in the southeastern Tenderloin neighborhood.”

It’s a far cry from when Compton’s Cafeteria was calling the police on the trans people of the Tenderloin.

Yet, I find myself wanting. In this era of intense backlash against transgender people, I suspect this will be a “first of its kind” for a long while. While the site of the Cooper Do-nuts Riot in Los Angeles is recognized, it’s not in the midst of a transgender district. The neighborhood around what had been Dewey’s lunch counter in Philadelphia, home of a 1965, pre-stonewall protest involving queer Black teens, has no trans flags on its traffic lights.

There are no transgender community districts in New York, in Chicago, in Houston, or elsewhere in the world.

At the same time, I wonder how many of the buildings around Turk and Taylor are owned by transgender and nonbinary people, how many businesses there can boast the same, and how those owners have taken to being in the transgender district of San Francisco. Beyond the flags, how much of this area is truly “ours.”

As I mentioned, we’re in a protracted backlash against transgender rights, with a majority of states now actively making it hard for their trans residents to hold jobs, get care, and be recognized for who they are. We now sit on the verge of Pride month, and see all the retailers who were showing support for the LGBTQ+ community pulling back. Most notably, Target has opted to not put Pride merchandise in many of its stores this year, handing a win to bigots.

We stand at a time when decades of progress is being pushed back. Come August, the Compton’s Cafeteria Riot will be 58 years old — but we now, once again, live in a time where stores and restaurants around the country can again call the police on transgender people simply for being ourselves.

At 101 Taylor are two plaques, commemorating the riot that took place all those years ago. I find myself wondering how many more plaques may be needed in the future, honoring those of us who have to again rise up for our rights, and try to change the work once more.

I visited a holy site the other day, and it sits in one of the few places we, as transgender people, might be able to call ours — yet, we need so much more.

Gwen Smith then went and visited the BLÅHAJ display at IKEA, but that’s a trans icon for another time. You can find her at www.gwensmith.com.