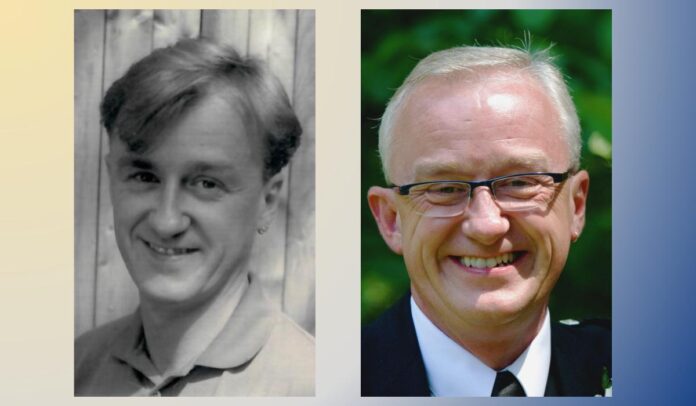

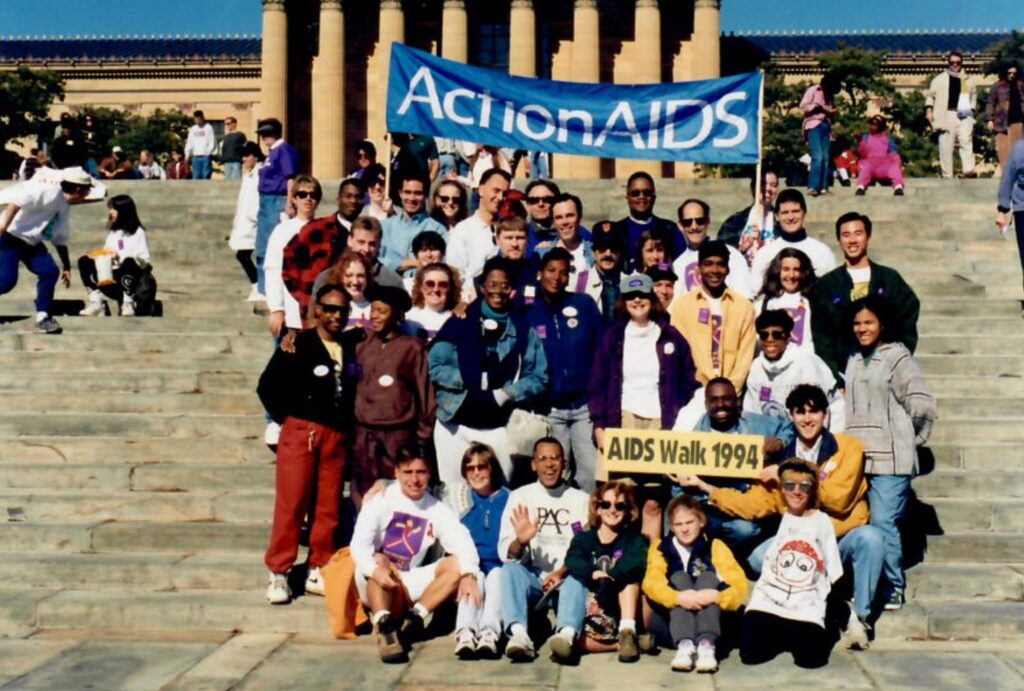

Kevin Burns, long-time executive director of the HIV/AIDS service organization Action Wellness, will retire this year in June. His work in the field began in 1986 when he served as a volunteer Buddy for Philadelphia Community Health Alternatives (now Mazzoni Center), which Action Wellness was part of at the time under a different name.

Burns then worked for Action Wellness for 34 years and served on the boards of numerous HIV-focused nonprofit organizations, including AIDS Fund, Dining Out for Life International, and Pennsylvania AIDS Law Project, among others. He also served on the Philadelphia Ryan White Planning Council for over a decade. Over the course of Burns’ career in HIV/AIDS service and activism, education, prevention, and the climate surrounding HIV/AIDS have transformed on multiple levels.

“I’m very proud and humbled to have played a small part in getting us to the place where HIV is a manageable disease,” Burns said. “I think about the early clients that I worked with, when we were essentially doing hospice work and making sure that people had what they needed to die with dignity. It’s so different today, thankfully. To feel like I played a small part in getting us to that point is the thing I’m most proud of.”

At AIDS Fund’s Black Tie GayBingo event on March 25, 2023, Burns will receive the Fierce and Fabulous Award for his work in the field of HIV care.

“I think that Kevin really approaches his work in a very collaborative way,” said AIDS Fund Executive Director Robb Reichard. “In working with other service providers, [he put] clients first in every equation.”

Beth Hagan, deputy executive director of Action Wellness, has worked with Burns at Action Wellness since 1990. She singled out his passion for working with clients.

“No matter what position he had at the agency, you could tell it was really his passion — that he really cared about people’s welfare, people getting the services they needed, and filling gaps for unmet needs,” Hagan said.

In terms of how the activism and messaging around HIV/AIDS has changed in the last 30 to 40 years, Burns said that despite progress, stigma connected to HIV/AIDS still proves problematic.

“We’re living in such a crazy time, who would have ever thought we’d be taking so many steps backwards,” Burns asked rhetorically. “I think it went from an unspeakable disease where it took how many years before President Reagan even uttered the words AIDS. And then it became sort of a cause celeb, if you will, where there was a lot of support from lots of different communities. And then it has sort of quieted down.”

Burns also posited that it’s more difficult today to get support for people living with HIV (PLWH) and to promote the current issues for PLWH. In some ways, it was easier years ago to get coverage around some aspects of HIV care, Burns said.

“I think of ACT UP, [they] always pushed the envelope and made sure we were staying front and center,” Burns said. “ACT UP Philadelphia is very small now, and some of that is because the disease now is a chronic, manageable disease.”

Another issue that Burns finds concerning is that some people living with HIV aren’t getting treatment and are still dying of AIDS, he said. “From my perspective, it’s poor people who don’t have any kind of access to health care who are still the ones that are dying of AIDS, who are sort of flying under the radar.”

Even though society has seen substantial progress in HIV medical treatment and prevention, “unfortunately, too many people in the general public take those successes and think HIV is no longer an issue,” Reichard said. “Here at AIDS Fund, we talk about getting to zero — zero new infections, zero stigma and zero deaths.”

He told a story about a young woman living with HIV who recently submitted an emergency financial assistance application to AIDS Fund. The family member with whom she was living kicked her out when they found out about her HIV status.

“Despite the strides we’ve made, stigma still exists out there and in ways that really impact people’s lives,” Reichard said. “I think in some ways I feel like we’ve come so far, and in some ways, when I hear a story like that, I realize — why in 2022 would somebody kick a family member out because they have HIV?”

Both Burns and Hagan underscored the fact that not only is housing a human right, but it’s also a significant factor in HIV care and prevention.

“Housing is an unmet need,” Hagan said. “It all ties into housing as prevention and housing as being able to remain in care for clients. I think that the advocacy has been different iterations. No less passionate, but just a different focus.”

Another component of perpetual barriers to HIV care is the nation-wide attack on LGBTQ rights, Burns pointed out.

“It’s almost as if we need to revive some of the techniques that ACT UP used, to be really clear that we’re not going to go backwards,” Burns said.

After he retires, Burns hopes to do volunteer work for political candidates who prioritize advocating for LGBTQ rights.

Going forward, Burns hopes for increased access to a range of HIV prevention and treatment services that PLWH need to live long, healthy lives. In order to expand its reach, Action Wellness leadership opened a new office in Kensington, developed by Shift Capital, which is committed “to create inclusive, equitable communities who thrive,” according to the development firm’s website.

“Above the office spaces, there are apartments that are affordable rental units,” Burns said. “I am really excited with this prospect of being able to work more with developers like that to do for-profit, nonprofit partnerships around housing. The truth is, if we wait for the government to solve the homeless issue and the housing shortage, we’re going to continue to do more of the same that we’ve been doing for the last 30 years.”

In 2016 Action Wellness, previously Action AIDS, expanded its services to people living with other chronic illnesses in addition to HIV. “Kevin was a really big part in that,” Hagan said. “[He always paid] homage and respect to where we started and who we are at the core, and complementing that with having a vision of where we could go.”