Part one of a three-part series.

At 69, Aviva Rosen says she is getting old.

“That 70 milestone is just months away, and leaving my 60s and heading into my 70s feels like a real sea-change,” Rosen said. “I’m not sure I’m ready. I’m not ready to retire and I’m not ready to not-retire. Money feels like it could be an issue for us. So does health. ”

Rosen’s partner of the past 19 years, Reece Davis, is 75. Davis, who retired last year from her job in health administration, says, “We are starting to have real worries about the stability of our future and what services there are for gay people like us who don’t have family to care for us as we age.”

Both women told PGN that their biggest fears were of being separated and forced to leave their small row home on a quiet tree-lined street in Northwest Philadelphia, the home where Davis has lived for over 30 years and the couple have lived together with their dogs for nearly 20.

“Our health is manageable now,” said Rosen, a social worker. “But we are well aware that we are one fall or one bout of pneumonia away from having to consider moving to assisted living, which we know is not queer-friendly. We just don’t want that. We want to stay here, together, for the rest of our lives.”

As the first generation of out LGBT people post-Stonewall is getting older, the concerns that Rosen and Davis voiced are increasingly common. Statistically, older Americans want to “age in place” and remain in their homes. Myriad in-home healthcare services have sprung up in recent years to address those needs and wishes. Yet as the New York Times reported earlier this month, so-called “kinless” seniors are a growing demographic, complicating those desires. The Times reported “An estimated 6.6 percent of American adults aged 55 and older have no living spouse or biological children, according to a study published in 2017 in The Journals of Gerontology: Series B.”

While Rosen and Davis are partnered, many older LGBT people fall into that category of lacking a spouse or partner, children and biological siblings. This is more true of gay men and trans people than of lesbians, yet the data on how LGBT people are aging, what their needs are, and if those needs are being met, remains disturbingly scant overall.

America itself is aging. Baby boomers — people born after World War II between 1946 and 1964 — remain a large U.S. age demographic. According to U.S. Census figures, there are more than 46 million older adults aged 65 and older living in the U.S. By 2050, that number is expected to reach 90 million. In Pennsylvania, the percentage of people 65+ is above the national average at 19%. That number has ticked up over three percent in the last ten years.

How do those numbers translate for LGBT people? The percentage of U.S. adults who self-identify as LGBT rose to a new high of 7.1% in 2022, according to a Gallup poll. That number is double the percentage from 2012, when Gallup first measured it.

According to this polling, among LGBT Americans, 57% identify as bisexual, 21% identify as gay, 14% as lesbian, 10% as transgender and 4% as something else. Those percentages translate into millions of LGBT people, and within those demographics are many LGBT elders.

The question some are working hard to answer is: what’s next for elderly LGBT people as they age? Organizations like Movement Advancement Project, SAGE (Services & Advocacy for GLBT Elders), Center for American Progress, and local programs like the William Way Community Center’s Elder Initiative are all working to compile data.

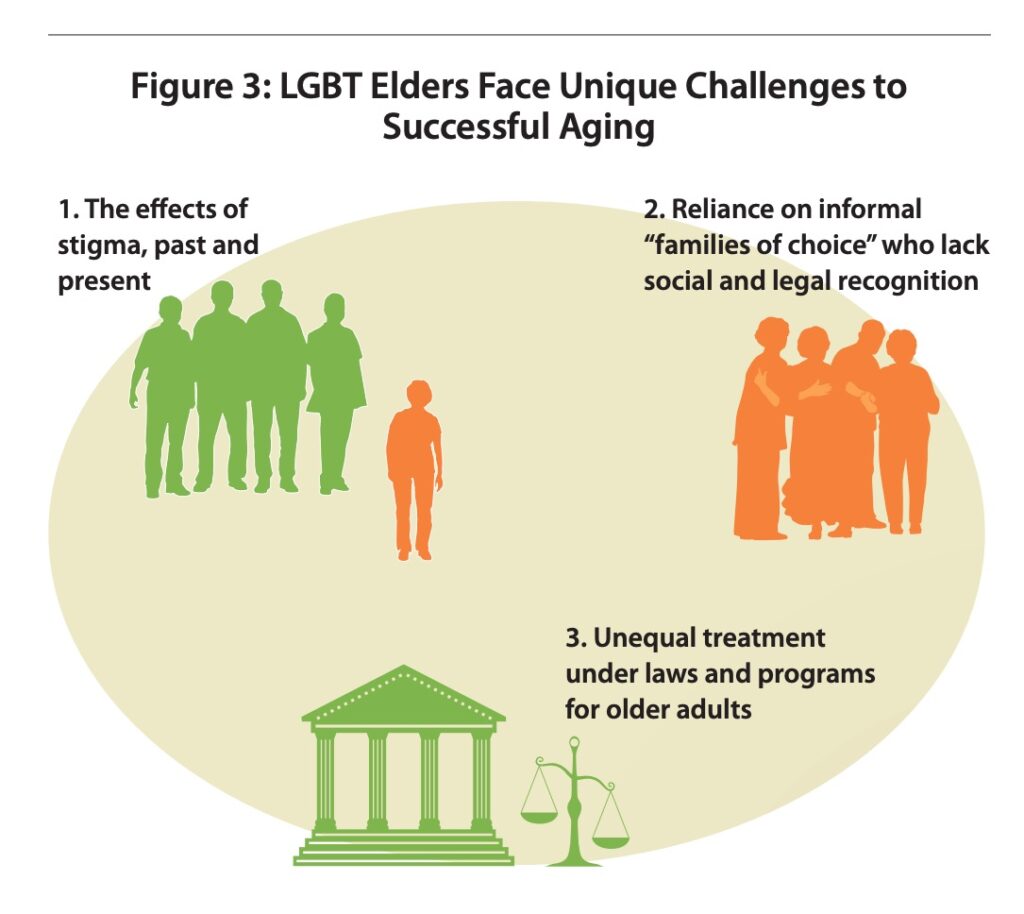

The Movement Advancement Project notes, “While confronted with the same challenges that face all people as they age, LGBTQ elders also face an array of unique barriers and inequalities that can stand in the way of a healthy and rewarding later life.”

Those barriers were increased in 2017 when the Trump administration put an end to vital data collection programs about LGBT seniors. The impact of this is still being felt, with the net result being to erase disparities and potential discrimination in federal programs.

Former Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) Tom Price — who has a long anti-LGBT history — eliminated questions about LGBT people from critical surveys. The Trump administration rolled back data collection on LGBT people who receive federal programs, which made assessment of whether programs for seniors were in fact getting to and meeting the needs of LGBT Americans.

The National Survey of Older Americans Act Participants is an annual national survey of people who receive services funded under the Older Americans Act (OAA), the primary vehicle for delivering social support and nutrition programs to older adults in the U.S. The National Survey started collecting data on LGBT program recipients in 2014. In 2017, HHS removed the survey’s only question about sexual orientation and gender identity.

Are LGBT elders being served as well as their cis-het peers? The American Psychological Association (APA) thinks not. APA says that “Psychological service providers and care givers for older adults need to be sensitive to the histories and concerns of LGBT people and to be open-minded, affirming and supportive towards LGBT older adults to ensure accessible, competent, quality care. Caregivers for LGBT people may themselves face unique challenges including accessing information and isolation.”

APA also says, “LGBT older adults may disproportionately be affected by poverty and physical and mental health conditions due to a lifetime of unique stressors associated with being a minority, and may be more vulnerable to neglect and mistreatment in aging care facilities. They may face dual discrimination due to their age and their sexual orientation or gender identity.”

APA says LGBT elders face “double whammy discrimination,” due to ageism and homophobia or transphobia.

And Center for American Progress reports that “LGBT older adults face acute levels of economic insecurity, social isolation, and discrimination, including difficulty accessing critical aging services and supports.”

Dr. David Vincent, Chief Program Officer with SAGE in New York City, talked to PGN about this discrimination, the lack of access that many LGBT elders have, and their trepidation in reaching out for help. He said that fear of judgmental responses to how people have managed their lives is a frequent impediment for LGBT elders, many of whom have had to contend with discrimination and under-employment which has left them less able to access paths open to their cis-het peers.

Vincent also talked about the financial issues facing many LGBT elders, issues that differ significantly from their cis-het peers. Vincent provides the leadership for all the direct service programs at SAGE, including care management, housing and behavioral health.

“What we see is the impact of a life of discrimination, exclusion and under-employment,” Vincent said. He also remarked that LGBT elders have had fewer opportunities to build wealth. “These are people whose access to wealth has been limited by their LGBT status — it’s not their fault they couldn’t have savings and a house and financial equity.”

Vincent said that those factors do make LGBT elders more concerned for their financial futures because they have “less for retirement.” He said 51% of LGBT elders are “fearful” of their financial futures as opposed to 36% of cis-het elders.

“We need to help our elders to live with dignity and without fear,” Vincent said. But how to make that happen will take a queer village and maybe a whole new liberation movement to make sure the people who fought for LGBTQ civil rights are not forgotten as they age.

Next week, we’ll look at the life-threatening impact of lack of access to healthcare and housing for LGBT elders.