By Neal Broverman

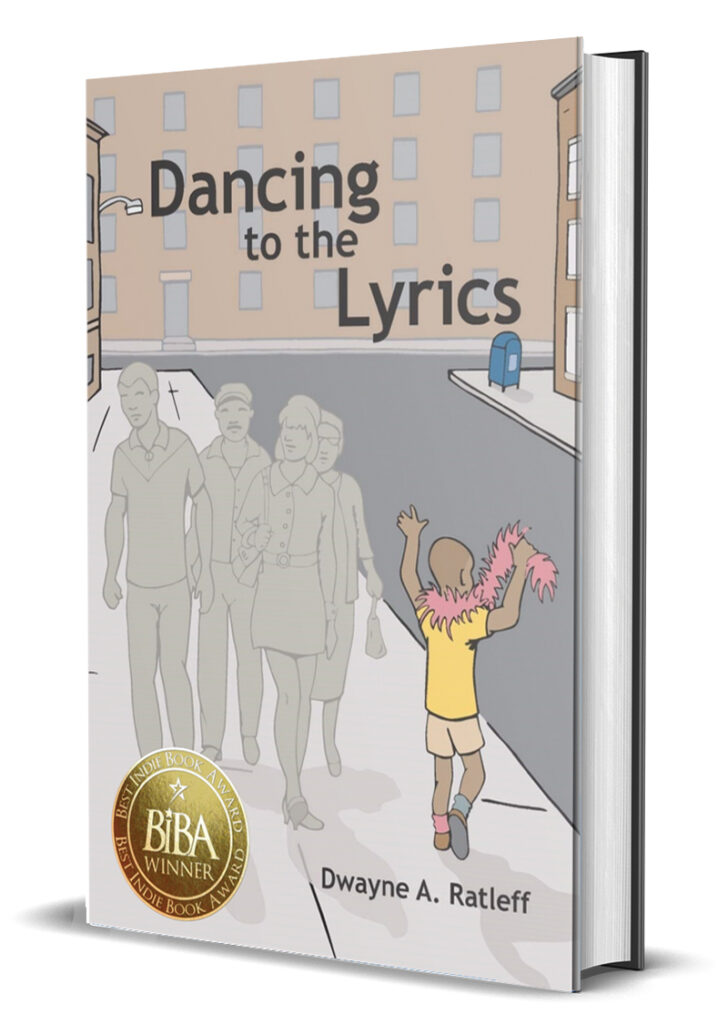

The Baltimore of Dwayne Ratleff’s 1960s childhood was not like the one director John Waters parodied in “Pink Flamingos” and “Hairspray,” or the dystopian wasteland depicted by HBO’s “The Wire,” or the hit song “Baltimore” from jazz icon Nina Simone. It was a flawed yet magical place, where horse-drawn carts sold fruit and vegetables, and paper boys sang while they hawked the day’s news. It was a city that shaped the future author and longtime HIV survivor. Ratleff chronicled his chaotic early days in the memoir, “Dancing to the Lyrics,” which received 2021’s Best Indie Book Award in the LGBTQ+ Coming of Age category.

“Every time I read something about Baltimore, particularly the 1968 riots, the writers often have had the opinions of individuals sitting in a soft cushion a comfortable distance away from the events,” Ratleff says. “I was very young, but I was in the city where it happened. My [complaining] would eventually turn into writing.”

Ratleff, who moved with his family from Ohio to Baltimore, Maryland, when he was 5, says his childhood city possessed a strong community that existed alongside very real mid-century urban ills like racism, poverty and crime. Ratleff himself was dealing with a stepfather who systematically abused his mother, exposing him and his two sisters to regular explosions of violence. In “Dancing to the Lyrics,” Ratleff describes how his troubled family life ran parallel to Baltimore’s own problems — the city would be engulfed by deadly riots following the April 1968 murder of Martin Luther King, Jr.

As the cover of “Dancing to the Lyrics” depicts, Ratleff wasn’t the most masculine child, but many elders accepted his femininity. He says it was mostly the church-going folk who chastised him for being different from other boys. Besides navigating homophobia and violence, Ratleff had another cross to bear — he was illiterate until his preteens. The fact that he learned to read at such a late age, only to bloom into an award-winning author, is not lost on Ratleff.

“There were many obstacles to writing this book,” he says. “But the more obstacles in your path, the greater reason to start the journey. As I did not learn to read or write until I was 10 or 11, I never felt comfortable with my writing ability. In addition, I lost the partial use of my left hand in an accident and could no longer type. But the need to tell my story banished all those concerns and with one finger I began to type my story. Despite the award I won for my book, ‘Dancing to the Lyrics,’ the real reward was learning I was very good at something I always feared I was very bad at.”

Ratleff hopes to follow up “Dancing to the Lyrics” with another book, possibly about his HIV diagnosis. Decades after having left Baltimore as an 11-year-old, Ratleff would test positive in early 1990, though he feels he actually seroconverted in 1982.

“The day I found out, I was very calm, not shocked at all,” Ratleff recalls. “The full impact hit me a couple of days later. It was Super Bowl Sunday. All of the sudden I am walking on the streets of San Francisco, and I started to cry uncontrollably. The 49ers had just defeated the Denver Broncos to win the Super Bowl. While I was crying everyone was on the street celebrating, laughing and smiling. The juxtaposition could not be more surreal.

“Suddenly a car full of young straight men pulls up alongside me and yells at me, ‘Yay 49ers!’ One of them notices me crying and says, ‘Leave him alone, he must be a Broncos fan.’ It was perhaps misguided sympathy, but it was sympathy nonetheless. It made me laugh briefly on a very dark day.”

Ratleff credits both his proactive nature and simple happenstance for his longevity. Though he was told after his diagnosis he would likely die in less than five years, he would prove his doctors very wrong.

“Luck kept me alive long enough for advances in treatment to develop and for me to take charge of my health,” he says

Now living in Palm Desert, California, with his husband and dog, Ratleff is taking time to recharge before starting his new book. As someone who’s survived a violent upbringing and an HIV diagnosis when it was a death sentence, Ratleff offers this advice for others seeking similar resilience: “I feel fortunate that I have moved on from the many traumatic experiences in my life. It may not be as simple as it seems, but you must turn your worst enemy into your best friend. That person very often is yourself. You are only truly alone when you, too, abandon yourself. There is far more to it than that, but that is a crucial step.”

Neal Broverman is the Editorial Director of Plus magazine. This column is a project of TheBody, Plus, Positively Aware, POZ and Q Syndicate, the LGBTQ+ wire service. Visit their websites — http://thebody.com, http://hivplusmag.com, http://positivelyaware.com and http://poz.com — for the latest updates on HIV/AIDS.