The news on November 26 that Stephen Sondheim had died was sudden and surprising. Although he was 91, Sondheim was not reported to be in ill health and had just spent Thanksgiving with friends.

The breadth of Sondheim’s musical oeuvre and concomitant genius will be written about extensively in the coming days and weeks — and for years to come — by music critics, musicologists and academics. I shall leave it to them to deconstruct his genius in those contexts, noting his many awards from Tonys to the Pulitzer Prize to Grammys.

But for some of us mere lovers of his music and often dark vision, Sondheim’s singular voice touched us personally. His death is mourned with all the keening depth we would bestow upon a close friend.

All over America piano bars are becoming impromptu tearful wakes for Sondheim. And as the pandemic rages on around us, so too are a myriad of American living rooms like my own, where Sondheim has been playing on loop since his passing.

I fell in love with Sondheim early. Ours was a musical household, one layered between the protest songs of my parents’ Civil Rights and anti-war activism, the American songbook by Ella Fitzgerald, and the original cast recordings of Broadway musicals.

It was among those albums that I discovered Carol Lawrence and Larry Kert singing the original Broadway cast debut of Sondheim’s and Leonard Bernstein’s “West Side Story.” My mother said they saw the preview at the Erlanger theater in Philadelphia, where it played for two weeks before opening at the Winter Garden Theater on Broadway in September 1957.

Like many queer kids, I fell in love with the rarified world of dreams coming true that most musicals presented and which always seemed out of reach for us, for me. Out of reach except in Stephen Sondheim’s musicals, where things were never quite as they seemed and where outsiders were the main characters, not in the background or on the margins. Sondheim’s lyrics that told us “Somewhere, there’s a place for us,” and we could truly believe it because the characters who sang these words were outsiders like us.

In his later years, Sondheim dismissed some of his earlier work as less refined and valuable than his later, more innovative musicals and songs, like the provocative “Assassins” and “Passion.” Sondheim’s devotees disagreed.

I first saw the electrifying 1961 film version of “West Side Story” on TV while in junior high and it was a revelation to me. The language of Sondheim’s lyrics, written when he was only 25, wasn’t like anything else in musical theater at that time. But those words resonated deeply — as did my attraction to the brilliance of Rita Moreno, who won an Oscar for her performance as Anita.

While in high school, “West Side Story” played at the iconic Germantown repertory theater, The Bandbox. Seeing it on the big screen was the most moving film experience I’d had to date. That initial frisson has never left me. I read a piece by Philadelphia linguist and musical theater professor Dr. John McWhorter, “Stephen Sondheim Wrote My Life’s Soundtrack,” and felt the same. From those first viewings of “West Side Story” with its many outsiders and the language of outsider status, Sondheim caught me up.

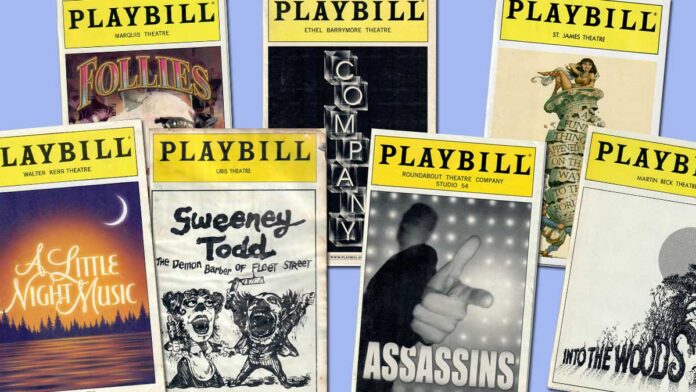

Later I saw “Company,” staged in New York at the college of a friend’s brother, and read it as an extraordinarily feminist statement. Then there was “Sweeney Todd,” a story of lost love and vengeance and cannibalism. Its cacophonous, dystopian ending is pure Sondheim, coming as it does after a musical-cum-opera that includes some of the most hauntingly beautiful and stylistically perfect love songs in musical history. How does one get the lyrical “Pretty Women” out of one’s head? With “A Little Priest.”

And on the extremity of “Passion”: isn’t obsessive love something to which we can all relate?

“Assassins” was met with bad reviews when it first opened off-Broadway in 1990 and ran for only 73 performances. But the 2004 revival won five Tony awards, including best revival of a musical. Were audiences just not ready for a musical about presidential assassins? Was it too dark in 1990 yet resonant for a country weary of George W. Bush and his torture and wars?

“Assassins” is brilliant, and it predated “Hamilton” by decades. It also speaks more directly even than “Sweeney Todd” to Sondheim’s questioning of the inherent evil within us as humans and how we deal with it. But Sondheim also addresses that in “Into the Woods” where the interplay of the fairy tales we’ve been raised on takes on a very different meaning. Yet “Into the Woods” is softened by the extraordinary score that includes the almost unbearably lyrical “No One Is Alone” in which Sondheim reminds us “people make mistakes.”

Did Sondheim’s own outsider status as a gay man influence his by turns rapturous and defamatory writing about romance and relationships? Is Bobby in “Company” a stand-in for Sondheim? Or is that Clara — or Fosca — in “Passion”?

Sondheim was a gay man who did not come out until he was 40 and did not live with a partner — dramatist Peter Jones — until he was 61. Sondheim married Broadway singer/actor Jeffrey Romley in 2017. Romley, 41, survives him. Sondheim’s own search for the love and acceptance he wrote about again and again eluded him often and long, and it has led the mainstream press to ignore the fact of his gayness and the role it played in his work.

The complicated nature of Sondheim on romance is part of his allure. There are few happy endings in Sondheim. Rather, there are epiphanies and self-awarenesses and even, at times, self-acceptance. Sondheim wrote of the emotional and relational complexities of both men and women with verve and pitch-perfect acuity. The women in his plays aren’t adjuncts and accouterments, they are vivid players in their own lives and they have yearning as well as agency. Are there more haunting soundtracks about the constricted role of women’s lives than “Company,” “A Little Night Music,” “Into the Woods” and “Passion”?

Sondheim’s language and his stories of the intricate and nuanced nature of love, longing, and oftentimes vengeance is singular. A friend, Stephen Robinson, wrote in his essay “Some Insufficient Words About Stephen Sondheim” that “Sondheim… believed in redemption and compassion. The world is nasty, brutish, and short, but we can make it less so if we care for others lost in the same wood. No one is alone.”

And this is why we shall mourn long and loudly for Sondheim and cry over his songs as we do so. For Sondheim’s 90th birthday — in the midst of the Broadway lockdown — Tony winner Raul Esparza sang “Take Me to the World,” from “Evening Primrose.” The 1966 song could not have been more resonant, as the character singing hopes to break free of a prison they have been trapped in since childhood. Sondheim’s lyrics resonate so much that they could have been written in 2020 for our pandemic year.

Stephen Sondheim took us to the world and then some. He crafted the stories and the soundtrack of our lives, he made space for us and gave us songs to sing that opened up our hearts even as they broke them. And for all of the immensity of that passion he wrote out for us till his final days, we shall be forever in his debt.