Alec Scudder, the gamekeeper in the novel (and film) “Maurice” has launched many gay fantasies. Now, 50 years after E.M. Forster’s classic gay novel was published, local playwright William Di Canzio has written a novel, “Alec,” that recounts the backstory of the character before overlapping with scenes from “Maurice” and carrying the lovers’ relationship forward into World War I and beyond.

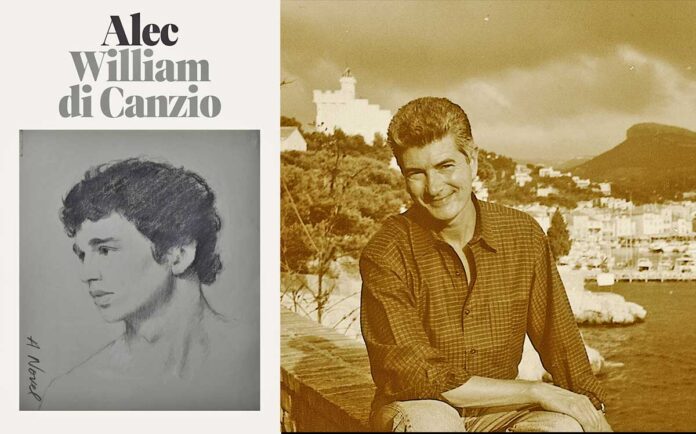

The book is a shrewd imagining of Alec’s life, from his first same-sex experiences to his efforts to be reunited with Maurice after the war separates them. The author, who will present “Alec” at the Free Library on July 15 at 7:30 pm, spoke with PGN about his new novel, which is both an homage to Forster as well as very much its own book.

What inspired you to write this novel? It is decidedly not in the same tone as Forster, and I appreciate you not trying to emulate his style.

I love Forster’s novel, “Maurice.” I had an instinct, a hunch, a desire that there was more of the story to tell. I read Wendy Moffat’s astounding 2012 biography of Forster, and my hunch was right. Forster himself had tried to write an epilogue and threw it out. The war destroyed the world in which the lovers had met. One reason why I love “Maurice” was the happy ending. Part of it is that Maurice is subjected to a lot of the shame that young gay people later in the century were subjected to. In his case, it was even worse because the lie he was being told was that his passions were criminal.

You include text from “Maurice,” some of which are scenes recounted from Alec’s point of view. Can you discuss that process of folding that book into yours?

The fiction of “Alec” accepts that the fiction of “Maurice” is real; that what happened in “Maurice” really happened. Part 2 of “Alec,” when the action converges, is towards the end of Maurice. I felt obligated to quote the dialogue in the scenes where the lovers are together. It was what they really said. Compare it to “Rosencrantz & Guildenstern are Dead.” In Stoppard’s play, when his action intersects with “Hamlet,” he quotes the original dialogue because that’s what they really said.

How did you imagine Alec’s story and what decisions did you make about his backstory and future?

Forster set out in “Maurice” to create a character who is unlike himself. Forster thought he was homely, and he was not good in sports and had an amazing intellect, so his hero is a noticeably handsome guy who is quite comfortable playing sports and really conventional. He has taken over his father’s investment firm. I took a cue from that for “Alec.” From a young age, Alec was not debilitated with religious or moral scrupulosity if you grow up, as I did, in a devout Catholic family. Where I suffered from doubt and shame, Alec has confidence. He knows who he is from an early age. I instilled him with self-awareness and confidence. That informs his whole character. The courage is manifest in my novel as he matures in his love for Maurice and through the Great War.

Almost everyone Alec meets is enamored with him, and almost all of the characters in the novel are gay men and they are portrayed positively. Can you talk about depicting homosexuality and attitudes toward homosexuality at the time?

Alec is a very nice looking young guy. Most of the characters he meets are attracted to him and are young men themselves. Part of my mission is to contribute by this novel to the documents of “the unrecorded history.” I know that is paradoxical, but “Maurice” is an artifact of “the unrecorded history” — that is Forster’s phrase for the lives and achievements of gay people, “a great unrecorded history.”

There are some rather erotic scenes between Alec and Van as well as Alec and Maurice. Can you talk about the depiction of intimacy in your novel, which is a bit more explicit than Forster?

Van is one of those guys who enjoys being admired. In addition to endowing Alec with confidence as a young person, it was also my determination that his first sexual experience would be good. There are so many examples of young people having rotten, predatory experiences. This will help to shape his character as well — that his first experience with a man who is kind, understanding, and wonderfully attractive. Alec is not enticed into this. He wants this experience, and it was my intention to present it beautifully, and romantically. My take on the love scenes and sexuality in the novel when Forster wrote “Maurice” he was in his mid-30s and sexually inexperienced. People complain the sex scenes are kind of awkward, but Forster kind of didn’t know what was going on, and that contributed to the writing the first draft. He revised it at least twice before it was published when he gained sexual experience. But he could have revised those scenes to be more detailed, but it’s a guess on my part that it was truer to the character of Maurice, whose only experience had been with Clive, and it was platonic and bloodless.

What can you say about the war scenes, which are vivid, as well as the postwar readjustment period which take up a significant portion of the novel?

I had to write them through the Great War. They were of the generation and exactly the right age to have fought. Their behavior, volunteering immediately, was typical of men of Maurice’s social class, but I think across the board, Englishman decided if you did not enlist you were unmanly or cowardly. There was also a classic trope of the ancient Greek tradition of same-sex couples fighting together that neither lover wished to be disgraced or considered a coward in the eyes of the other lover.

William Di Canzio discusses “Alec” in a free, virtual conversation with Wendy Moffat via the Free Library of Philadelphia on July 15 at 7:30 pm. For more information visit:https://libwww.freelibrary.org/calendar/event/106968