Black History Month 2021 is like no other, including the many historic firsts in President Biden’s administration.

The first woman and first Black person to be elected Vice President, Kamala Harris stands as a singular figure in U.S. history. So too does Lloyd Austin, the first Black Secretary of Defense. And Karine Jean-Pierre is the first out lesbian to be appointed Principle Deputy White House Press Secretary. And after a year that saw thousands of racial justice protests nationwide over the killing of Black people by police, as well as a pandemic that disproportionately infected and killed Black and brown people, Biden and Harris have worked together to address issues of racial discrimination and racial inequities through proposed policy and executive orders.

There is always much to celebrate for Black History Month. But Black LGBTQ voices have often been hidden in mainstream highlights of Black history. Yet these voices are not only pivotal to our collective American and LGBTQ history, they have much to teach white Americans at a time when dealing with the raw and present wounds of racism and white supremacy is crucial to moving the country forward on a path of true inclusion and real justice.

As AIDS and trans activist Marsha P. Johnson said, “History isn’t something you look back at and say it was inevitable, it happens because people make decisions that are sometimes very impulsive and of the moment, but those moments are cumulative realities.”

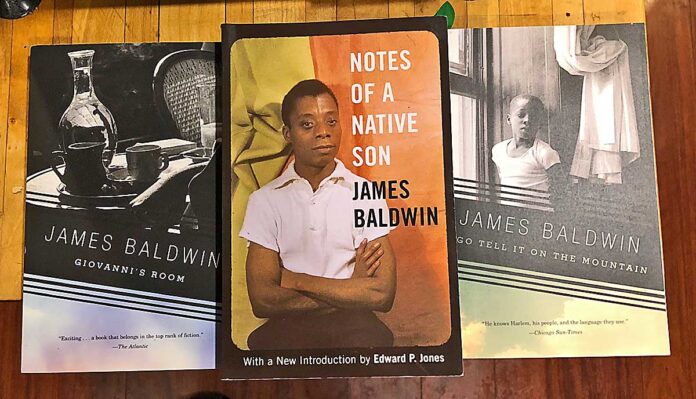

There is perhaps no more critical voice on racial justice and those “cumulative realities” than Black gay writer, playwright, poet and activist James Baldwin. “Notes on a Native Son” and “The Fire Next Time” are central historical texts in the discourse on race in America. As Baldwin noted, “Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.”

Audre Lorde, another important voice, was a major force in lesbian feminist politics and literature. Her complex deconstruction of race and gender and sexual orientation in books like “Sister Outsider” directed a whole movement within lesbian feminism. Her classic statement, “The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house,” served as both warning and admonition to activists about what can be achieved and how to do so when addressing the twin threats of white supremacy and patriarchal male dominance. But Lorde was equally undaunted when she took on the whiteness of feminism in the 1960s and 1970s, determined that Black lesbian feminist voices not be suppressed.

Lorde was also succinct about the impact of women on the battle against white and male supremacies, noting, “Women are powerful and dangerous.” She wrote unstintingly of the importance of lesbian erotic life. as well as the politics of being a “radical feminist lesbian warrior.”

Baldwin and Lorde engaged in a groundbreaking dialogue at Hampshire College in Amherst, Massachusetts in 1984. “Revolutionary Hope: A Conversation Between James Baldwin and Audre Lorde,” was later published in part by ESSENCE magazine. The two activists debated issues of gender politics and sexual orientation, as Lorde explored the impact of being a Black lesbian in white America and Baldwin talked about the “schizophrenia” expected of Black men in a white-male-driven society.

There are many other queer Black voices whose focus looms large now as we strive to address the dangers of white nationalism. Pauli Murray is often neglected as a pivotal Black queer voice. The civil rights activist, attorney and Episcopal priest fought what she termed “Jane Crow,” the ignoring of the impact of racism on women.

Murray’s speech, “Jim Crow and Jane Crow,” delivered in Washington, DC in 1964, addresses the sexism and racism — what we now term misogynoir — that Black women face. Murray said, “Not only have they stood with Negro men in every phase of the battle, but they have also continued to stand when their men were destroyed by it… One cannot help asking: would the Negro struggle have come this far without the indomitable determination of its women?”

Murray repeatedly called out the lack of attention paid to and failure to elevate Black women within the civil rights movement.

Yet Murray was a legal scholar and star within the movement. Thurgood Marshall called her book “State’s Laws on Race and Color” the “bible of the civil rights movement.”

Murray was also a co-founder of the National Organization for Women (NOW) and was co-author of a 1971 brief by Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Murray was also the first Black woman to be ordained an Episcopal priest in the U.S.

Murray identified as a lesbian and had several long-term relationships with other women, but she struggled with that identity as well as with her gender identity, and she wrote heartbreakingly of those struggles in “Song in a Weary Throat: Memoir of an American Pilgrimage.” Perhaps if she were born in a different era she might have transitioned, as some writings about her have suggested. Her volume of poetry, “Dark Testament,” was republished in 2018.

Murray said, tellingly, “If anyone should ask a Negro woman in America what has been her greatest achievement, her honest answer would be, ‘I survived!’”

That this quote could be said in 2021 and be equally accurate is another reason to read Murray’s work.

Marsha P. Johnson is always identified with the Stonewall Rebellion and with her work as an AIDS activist, but much her activism was primarily focused on the disproportionate number of Black Americans incarcerated in prisons and jails and how gay, lesbian and trans people were in turn disproportionately represented among those people.

Johnson and her close friend Sylvia Rivera co-founded the Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR) organization. They also ran the STAR House, a shelter for gay and trans street kids in 1972, where they paid the rent with money they made themselves as sex workers.

In 1992, just before she died, Johnson was at the unveiling of the George Segal commemoration to Stonewall on Christopher Street. She said, “How many people have died for these two little statues to be put in the park to recognize gay people? How many years does it take for people to see that we’re all brothers and sisters and human beings in the human race?”

That queer Black voices of the past speak directly to the urgency of now is incontrovertible. Baldwin wrote in one of his essays, “You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read.” It is essential that we take up the works of these iconic Black LGBTQ figures and do as Baldwin instructs: Read.

The dialogue between Baldwin and Lorde can be read here.