In the Jan. 3, 1976 issue of PGN, Harry Langhorne wrote an article about Bill 1275, which was introduced in City Council in the spring of 1974. The bill sought to amend the city’s Fair Practices Act to prohibit sexual orientation discrimination in housing, public accommodations and employment.

The years following Stonewall had seen both advances and setbacks in LGBT rights. By the mid-’70s, several cities had passed nondiscrimination bills, and 13 states had repealed sodomy laws, but much of that legislation was repealed after community backlash. Police were still raiding bars, people were still being fired from their jobs, and states had begun to ban same-sex marriage officially. Even the various LGBT groups were torn over whether to fight alongside African-American and women’s’ equality efforts or to focus exclusively on the LGBT community. It was in this back-and-forth climate that Philadelphia activists lobbied City Council to pass Bill 1275.

The Council President at the time George X. Schwartz was not friendly to the LGBT community, same with Councilman Isadore Bellis, whose law and government committee was assigned the bill. Gay Activists Alliance, whose members included Langhorne and PGN publisher Mark Segal, had secured support from numerous community groups, including the Episcopal Diocese, the United Automobile Workers’ Union, the NAACP and the Pennsylvania Democratic Platform. However, Bellis still refused to hold hearings on the bill, without which the bill could not be voted on.

Instead, the bill was passed to the Human Relations Commission, which enforces the Fair Practices Act. After testimony from gay rights groups and opposition from fundamentalist religious organizations, among others, the Commission endorsed the bill and sent it back to City Council. The conservative leadership could no longer postpone hearings. On the day, Council President Schwartz brought in Archbishop John Krol, who appeared in full religious attire.

Langhorne described the hearings in his original article: “The fundamentalists were joined this time by the Police and Firemen, who claimed that their morale was too fragile to hold up if they had to work side by side with open Gays. And while the fundamentalists had become a little crazier this time, Bellis and Schwartz allowed them to rant for ten minutes about Gays being “possessed by devils” without a murmur of objection. Yet when a gay woman attempted to testify about some of the patterns of social discrimination that we face, which would not be affected by the bill, she was cut off at once.”

After the hearings, some Council members persuaded activists to wait on further action for the bill until after the primary election, which led to a subsequent delay until after the general election. By that point, it became clear that Council was not going to bring the bill out of committee and hold a vote. Groups such as GAA and Dyketactics mobilized protests in City Hall, including a hunger strike and a full takeover of Council chambers where people shouted “Free 1275!” The Civil Disobedience Squad, a group of police officers assigned to break up protests and haul people away, attacked members of Dyketactics on several occasions, throwing them to the floor and beating them.

But the in-your-face, militant tactics were unsuccessful, and Bill 1275 was never brought to vote. Philadelphia would have to wait seven more years, until 1982, for a nondiscrimination bill to get passed. During that time, the community was forced to debate which tactics worked best to help enact pro-LGBT legislation. Some said that the activists’ groups at the time were too small and too male-centric and that most laypeople knew nothing about Bill 1275 — thus had no investment in its outcome. The debate on whether to use nonviolent or militant protest had advocates on both sides. And the concept that ally organizations needed not just to pledge support for LGBT rights, but also put pressure on politicians to vote for it, was expanded.

It was this debate, and the efforts that came out of it, that led to Philadelphia becoming one of the first cities in the country to pass — and keep — a nondiscrimination bill. Activists brought on even more organizational allies, including The National Organization for Women, and focused specifically on recruiting more diverse lobbyists and drawing new people to the movement. The work those activists did is a road map for activists today, both locally and nationally, on how to navigate the political system and make meaningful change. As Mark Segal said in his very first “Mark My Words” column, ‘Philadelphia’s gay community will be back in full support of the new bill — this is a dream coming true.’

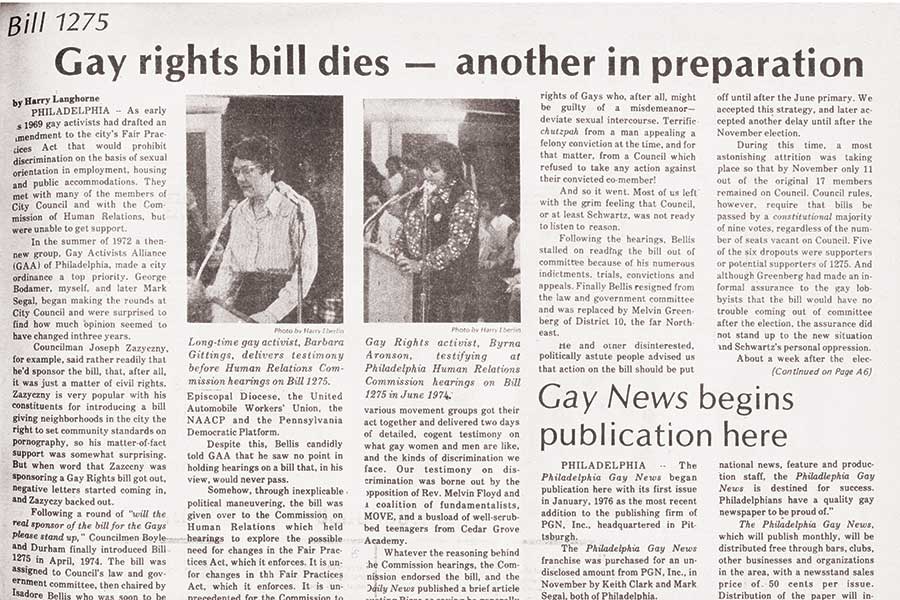

Original Article: “Gay rights bill dies — another in preparation” by Harry Langhorne on January 3, 1976 (p. 3)

As early as 1969 gay activists had drafted an amendment to the city’s Fair Practices Act that would prohibit discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation in employment, housing and public accommodations. They met with many of the members of City Council and with the Commission of Human Relations, but were unable to get support.

In the summer of 1972 a then-new group, Gay Activists Alliance (GAA) of Philadelphia, made a city ordinance a top priority. George Bodamer, myself, and later Mark Segal, began making the rounds at City Council and were surprised to find how much opinion seemed to have changed in three years.

Councilman Joseph Zazyczny, for example, said rather readily that he’d sponsor the bill, that, after all, it was just a matter of civil rights. Zazyczny is very popular with his constituents for introducing a bill giving neighborhoods in the city the right to set community standards on pornography, so his matter-of-fact support was somewhat surprising. But when word that Zazyczny was sponsoring a Gay Rights bill got out, negative letters started coming in, and Zazyczny backed out.

Following a round of “will the real sponsor of the bill for Gays please stand up,” Councilman Boyle and Durham finally introduced Bill 1275 in April, 1974. The bill was assigned to Council’s law and government committee, then chaired by Isadore Bellis who was soon to be embroiled in a still-continuing series of indictments and trials for bribery and corruption.

While GAA was looking for sponsors in Council, the group was also looking for endorsement from nearly every organization in the Whole City Catalogue, if no the Yellow Pages. Forty-six local endorsements eventually came in, including the Bar Association, the Psychiatric Association, the Episcopal Diocese, the United Automobile Workers’ Union, the NAACP, and the Pennsylvania Democratic Platform.

Despite this, Bellis candidly told GAA that he saw no point in holding hearings on a bill that, in his view, would never pass.

Somehow, through inexplicable political maneuvering, the bill was given over to the Commission on Human Relations which held hearings to explore the possible need for changes in the Fair Practices Act, which it enforces. It is unprecedented for the Commission to hold hearings after legislation has already been introduced.

Perhaps Bellis hoped the Commission would fail to endorse the bill and it could be allowed to die right there. The director of the Commission is appointed by the mayor, and perhaps Mayor Rizzo didn’t want the Commission to implicate the administration without the protection of hearings.

In any case, activists from various movement groups got their act together and delivered two days of detailed, cogent testimony on what gay women and men are like and the kinds of discrimination we face. Our testimony on discrimination was borne out by the opposition of Rev. Melvin Floyd and a coalition of fundamentalists, MOVE, and a busload of well-scrubbed teenagers from Cedar Grove Academy.

Whatever the reasoning behind the Commission hearings, the Commission endorsed the bill, and the Daily News published a brief article quoting Rizzo as saying he generally supported the idea of protecting the rights of homosexuals. But, Rizzo said, “I will have to study” the specific bill before taking any stand on it. “I’m for everybody’s rights,” he added expansively.

With the Commission hearings over, Bellis was no longer in a position to refuse to have committee hearings, without which no bill can be voted on in Council. Hearings were scheduled on two separate days in late December, 1974 and early January, 1975.

The fundamentalists were joined this time by the Police and Firemen, who claimed that their morale was too fragile to hold up if they had to work side by side with open Gays. And while the fundamentalists had become a little crazier this time, Bellis and Council president George X. Schwartz allowed them to rant for ten minutes about Gays being “possessed by devils” without a murmur of objection. Yet when a gay woman attempted to testify about some of the patterns of social discrimination that we face which would not be affected by the bill, she was cut off at once.

The gay testimony was again excellent, and our restraint was admirable until Schwartz began baiting witnesses, particularly Mark Segal, whom he repeatedly asked questions about his personal sexual behavior.

Bellis wasn’t much better. A lawyer who had himself previously amended the Fair Practices Act and knows it backward and forward, Bellis deliberately misled witnesses and created the false impression that the bill would cover rental of rooms in private houses. Bellis also questioned whether Council should protect the civil rights of Gays who, after all, might be guilty of a misdemeanor—deviant sexual intercourse. Terrific chutzpah from a man appealing a felony conviction at the time, and for that matter, from a Council which refused to take any action against their convicted co-member!

And so it went. Most of us left with the grim feeling that Council, or at least Schwartz, was not ready to listen to reason.

Following the hearings, Bellis stalled on reading the bill out of committee because of his numerous indictments, trials, convictions and appeals. Finally, Bellis resigned from the law and government committee and was replaced by Melvin Greenberg of District 10, the far Northeast.

He and other disinterested, politically astute people advised us that action on the bill should be put off until after the June primary. We accepted this strategy, and later accepted another delay until after the November election.

During this time, a most astonishing attrition was taking place so that by November only 11 out of the original 17 members remained on Council. Council rules, however, require that bills be passed by a constitutional majority of nine votes, regardless of the number of seats vacant on Council. Five of the six dropouts were supporters or potential supporters of 1275. And although Greenberg had made an informal assurance to the gay lobbyists that the bill would have no trouble coming out of committee after the election, the assurance did not stand up to the new situation and Schwartz’s personal oppression.

About a week after the election, with only three weeks left in Council’s current session, it became clear that the bill was not going to come out of committee at all unless overwhelming pressure could be mounted. This was critical since introducing a new bill in the 1976 session would mean finding new sponsors (Boyle and Durham are not on the 1976 Council), and holding new hearings.

Although about 70 people showed up at the next two council meetings, the pressure felt short of overwhelming. The gay presence in Council was organized quickly by an ad hoc group of activists in and outside GAA. The first week there were no disruptions. During the next week, Mark Segal began a hunger strike in Greenberg’s reception room during the day and outside in City Hall courtyard in 20-degree weather during the night. The following day he was joined by Rev. Don Borbe of the Metropolitan Community Church of Philadelphia and two others.

Meanwhile, a group of some eight women calling themselves “Dyketactics!” planned to “electrify the imaginations of the gay and women’s communities” with a strong protest if the bill did not come out of committee. Displaying signs and wearing pink triangles (which the Nazis made homosexuals wear in concentration camps) didn’t electrify as well as chants.

When it became clear that Greenberg was not going to bring 1275 out of committee, Dyketactics led the group in chanting “Free 1275 out of committee. Dyketactics!” Disobedience (CD) Squad moved in through the chanting crowd and came down hard on the women, who were thrown to the floor, kicked, and beaten. At one point during the melee, Councilwoman Ethel Allen shouted for a guard to stop beating one of the women. The Gays were all cleared from the room although none were arrested.

Outside Schwartz’s office, Dyketactics put on a guerilla theater skit using a 13-foot high witch puppet. As they were leaving, they were again attacked by the CD squad in plain view of students who had been touring the building. Six of the women required treatment at Philadelphia General Hospital and are bringing suit against the CD squad for use of excessive force.

Planning for the introduction of a new bill has not yet begun, but some ideas have already been formed about community tactics. The lobbying team of the past is seen as too small and closed with the result that not enough people know about the bill or feel implicated in its success or failure. Lesbians especially have felt excluded from the efforts in behalf of 1275.

There is also an apparent consensus for more militant pressure tactics, with the strongest support coming from Dyketactics. Although more endorsements from non-gay groups are important as well as a deeper commitment from the groups which have already endorsed, the example of New York’s latest defeat on a gay rights bill shows us that not even the most star-studded cast of straights can get the bill out of committee.

And the New York defeat came after a militant gay presence at Council hearings, so there may well be a danger of overplaying pressure tactics here as well.

The new Council will have eight new members. Three are Rizzo councilpeople: Pearlman, Vann, and another not as yet elected to fill the O’Donnell vacancy—all at-large council seats. There are also two Rizzo councilpeople from districts: Anna Verna and James Tayoun. Tayoun may be even more homophobic than Schwartz.

Two new councilmen, Lucien Blackwell and Cecil Moore, from West and North Philadelphia respectively, are independent Democrats and both politically experienced. The Rizzo slate, however, is generally inexperienced and may be reluctant to tackle a controversial issue anytime soon. In addition, they are socially conservative and represent conservative constituencies.

Fortunately, Lucien Blackwell has already expressed his willingness to be the prime sponsor of the new gay rights bill, and four other councilpeople are currently considered likely co-sponsors for the bill. While no definite date has as yet been set for introduction of the bill, it is hoped that it will be introduced as soon as possible so the complex and lengthy process of hearings can begin.