The history of lesbian literature is, for many of us, a critical piece of our own personal lesbian history as well as our larger LGBT history. Novels, poems and essays have so often opened up the queer world for us –– we’ve seen the words of other lesbians and recognized ourselves in those words. Sappho may have been the first lesbian poet, but there have been many others whose words and work have helped us understand our own hearts and experiences.

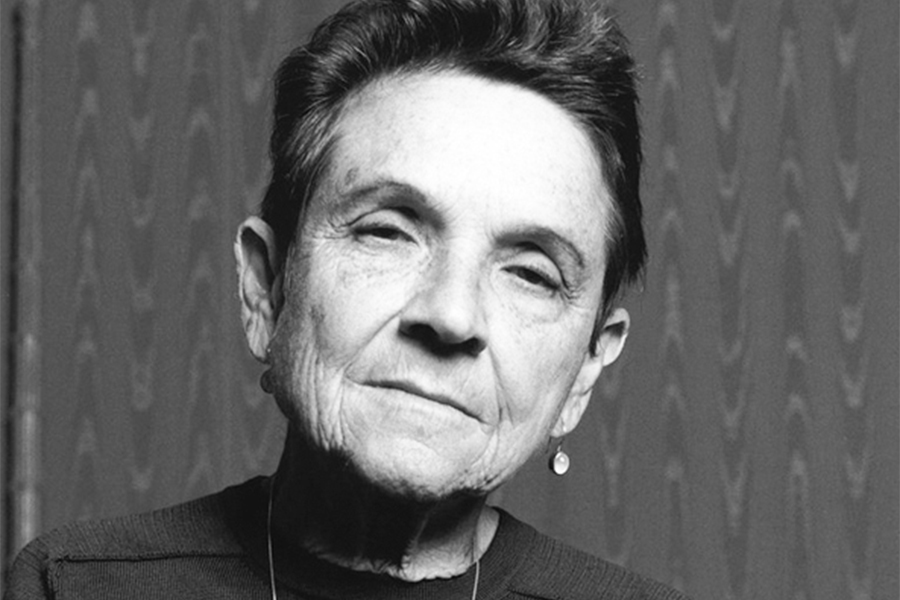

Adrienne Rich was one of the most important poets of the 20th and early 21st centuries.

Rich was a cartographer of her times. Born May 16, 1929, she grew up in Baltimore, where she was home-schooled until she was 10. She attended Radcliffe College, where she studied poetry and writing, graduating in 1951. Her first collection of poetry, A Change of World, was chosen soon after for the Yale Younger Poets Award, the choice of the great gay poet, W.H. Auden.

That auspicious beginning propelled her forward to a Guggenheim Fellowship, a year in Italy where she wrote continually and then back to the U.S., where she married Alfred Conrad, the father of her three sons, David, Paul and Jacob.

Conrad was an economics professor at Harvard whom she met at college. The marriage was fraught from the start, as Rich wrote. But it was motherhood that propelled her into her feminism and, as she wrote, “radicalized me.”

Rich’s radicalization — detailed in several books of essays — propelled her toward life as a lesbian.

Throughout the 1960s, Rich was a committed activist as well as mother and poet, engaged in the movements for civil rights, feminism and protesting the war in Vietnam. She wrote, “The serious revolutionary, like the serious artist, can’t afford to lead a sentimental or self-deceiving life.”

But that activism — she was hosting Black Panther parties and feminist salons in the family’s New York apartment — decimated her already rocky marriage. After accusing Rich of “losing her mind” because her feminist politics had become so all-encompassing, Conrad separated from her. Four months later, he shot himself to death. Their youngest son was only 11.

Six years after her husband’s suicide, Rich became lovers with Jamaican-American lesbian writer Michelle Cliff. The two were partnered for 36 years until Rich’s death in 2012 at age 82. Cliff died in 2016.

Prolific as she was political, Rich wrote assiduously, even as she raised her three sons alone. In the six years between Conrad’s death and her relationship with Cliff, Rich published six books of poetry.

Politics informed both Rich’s life and her art. She saw writing and activism as inextricable from each other. Her perspective was that art was transformative and everything was political — most especially the lives of women and other marginalized people. She wrote, “If you are trying to transform a brutalized society into one where people can live in dignity and hope, you begin with the empowering of the most powerless. You build from the ground up.”

That period of change wrought by the 1960s turned into the deeply feminist 1970s. Rich had moved fully into the lesbian-feminist subculture of that time. She had always lived a life of privilege — her father was a world-renowned pathologist and her mother was a concert pianist — and some lesbian-feminists questioned her “credentials” in that period of extreme activism and the intensity of the Second Wave of American feminism, where class privilege was discussed in earnest for the first time since the 1930s. While there were many women who left their husbands for other women in those years, suspicion still hung over those women and Rich was, coming out in her 40s, for a time, among them. But she declared in an interview with the London newspaper, The Guardian, in 2002, that after her husband’s death, “The suppressed lesbian I had been carrying in me since adolescence began to stretch her limbs.”

Rich’s anger and frustration with the complexities of her life — as a woman, a former wife, the mother of sons, a lesbian, an undeclared Jew (her father was Jewish but she and her sisters were raised Protestant) — was revealed in her poetry during the years between 1970-80.

Rich was developing a more and more radical feminism. Her lesbianism was overt — she was in no closet — and she was advancing her lesbian politics in her essays and poetry, which now included a book of blatantly lesbian love poems for Cliff, “Twenty-one Love Poems.”

In 1976, Rich re-defined herself in earnest in her groundbreaking feminist treatise, “Of Woman Born: Motherhood as Experience and Institution.”

In that book she wrote, “Much male fear of feminism is the fear that, in becoming whole human beings, women will cease to mother men, to provide the breast, the lullaby, the continuous attention associated by the infant with the mother. Much male fear of feminism is infantilism — the longing to remain the mother’s son, to possess a woman who exists purely for him.”

Even four decades later, such writing still rails against a world where Donald Trump is president and Brett Kavanaugh is on the U.S. Supreme Court.

Rich’s book received mixed reviews. The personal nature of her poetry and essays was suddenly suspect because as a lesbian, she was suspect. Yet the most defining male poets of her same generation wrote exceptionally personal work. Certainly when one considers the work of the man who granted her first award, W.H. Auden, one can hardly imagine how Rich’s work was somehow more personal than his. But Rich was re-inventing poetry from the vantage point of the female gaze. She was doing what Ralph Ellison and James Baldwin, Langston Hughes and Zora Neal Hurston had done as black writers — she was recreating the writers’ world from the perspective of the permanent underclass that was women.

Rich’s voices were those of women — mothers, wives, daughters, daughters-in-law, lovers, mistresses, lesbians. She wrote, “The connections between and among women are the most feared, the most problematic and the most potentially transforming force on the planet.”

In her poetry and essays, she was exemplifying what it meant to be female in every aspect of life. It earned her more than one epithet of “shrill” over the years.

And yet, she persisted.

There is perhaps no more important essay from Rich than “Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence,” in which Rich urges women to direct their energies to other women and away from men. About this essay, Alison Kafer argues in “Journal of Women’s History,” that “Rich argues that heterosexuality is not ‘natural’ or intrinsic in human instincts, but an institution imposed upon many cultures and societies that render women in a subordinate situation. It was written to challenge the erasure of lesbian existence from a large amount of scholarly feminist literature. It was not written to widen divisions, but to encourage heterosexual feminists to examine heterosexuality as a political institution which disempowers women and to change it.”

The most defining collection of poems from that period of change for Rich was Diving into the Wreck, for which she won the National Book Award in 1974. Proving that she lived her politics, Rich declined to accept the award individually. Instead, she accepted it “on behalf of all women” with fellow nominees, both black lesbians, Audre Lorde and Alice Walker.

The title poem has become iconic for its tales of women’s lives, never seen before in such vivid and visceral detail. In that poem Rich writes, “The words are purposes/the words are maps.”

Throughout the final quarter century of her life, Rich’s work was reflective of a deeply emotional poet whose feminism never wavered — whose politics remained solidly lived. In 1997, she was awarded the National Medal of Arts, which she also declined. Of her action, she wrote, “I could not accept such an award from President Clinton or this White House because the very meaning of art, as I understand it, is incompatible with the cynical politics of this administration. [Art] means nothing if it simply decorates the dinner table of the power which holds it hostage.”

Over her literary career Rich won a myriad of awards, including the Bollinger Prize, the Frost Medal, the Wallace Stevens Award, the William Whitehead Award, the Shelley Memorial Award and a MacArthur Fellowship (the so-called genius grant). She was awarded an honorary doctorate from Harvard. Rich taught at some of the most prestigious colleges, including Swarthmore, Columbia, Brandeis and Bryn Mawr.

In her work, Rich wrote of a world in which lesbians had full equality, autonomy and acceptance, where lesbian lovers were as valued and lauded as their heterosexual compatriots. Rich also wrote about the need for class consciousness and economic equity, among other things. In 2005, she said in an interview with the San Francisco Chronicle, “For me, socialism represents moral value — the dignity and human rights of all citizens. That is, the resources of a society should be shared and the wealth redistributed as widely as possible.”

The last 20 years of her life, Rich was in severe pain, crippled by rheumatoid arthritis. Her death was attributed to complications from the disease.

One of the most lauded poets of our time, Rich was never Poet Laureate; perhaps a political decision, perhaps just an inexplicable oversight. But her oeuvre, her work, her life all combined to break ground for a generation of women and women poets. Her work detailed the journey toward full personhood for women, queers, people of color, the poor and the incarcerated.

She wrote of the erasure of lesbians and other marginalized people: “Whatever is unnamed, un-depicted in images, whatever is omitted from biography, censored in collections of letters, whatever is misnamed as something else, made difficult-to-come-by, whatever is buried in the memory by the collapse of meaning under an inadequate or lying language — this will become, not merely unspoken, but unspeakable.”

Rich never ceased to speak about those who had been rendered voiceless. In the history of LGBT letters, her words illuminate the struggles lesbians face. She wrote, “There must be those among whom we can sit down and weep and still be counted as warriors.”

Rich was always a lesbian warrior.