Philadelphia District Attorney Larry Krasner met with trans attorney Julie Chovanes for an hour last week and expressed support for transparency in the Nizah Morris homicide case.

PGN was present during the meeting, which was mainly off the record.

Chovanes, executive director of Trans Help Inc., filed a state Right-to-Know Law request in April for all Morris records at the District Attorney’s Office. The law allows citizens to request public records from agencies.

“So far, I am extremely encouraged by District Attorney Krasner’s approach,” Chovanes told PGN after the meeting. “He has shown an excellent grasp of the issues involved. He’s also acknowledged a need to recognize the victim’s family’s — and the public’s — right to know all we can about this horrific incident.”

Morris was a transgender woman found by a passerby with a fatal head wound 15 years ago, shortly after the victim received a “courtesy ride” from Philadelphia police. Her homicide remains unsolved.

After the June 13 meeting, Ben Waxman, a spokesperson for Krasner, said: “We are committed to achieving justice for all victims and hope to be as transparent as possible in this case. Beyond that, we don’t have any public comment at this time.”

Babette Josephs, chair of the Justice for Nizah (J4N) committee and a longtime Pennsylvania state representative, didn’t attend the meeting, but praised Krasner for supporting transparency.

“Larry Krasner has always shown himself to be a man of integrity,” said Josephs. “I’m not surprised he’s expressing support for transparency in the Morris case. Nizah’s family and friends — along with the general public — deserve to know what happened to her. If Mr. Krasner can help bring us closer to that goal, we should all be grateful.”

The full extent of the D.A.’s holdings in the Morris case remains publicly unknown. It also remains to be seen whether Krasner will decide to release all Morris records given the existence of statutes limiting public access to records relating to a criminal investigation.

The incident took place during the early-morning hours of Dec. 22, 2002, outside Key West Bar, where Morris had been attending a Christmas party. Morris was intoxicated and a 911 call was placed on her behalf. Officers Elizabeth Skala and Kenneth Novak were dispatched to investigate. Skala arrived at the location first and offered to take Morris home. However, Morris lived at 50th and Walnut streets in West Philadelphia and Skala never transported her there. Instead, Skala transported Morris about three blocks — to the area of 15th and Walnut streets, the officer told investigators.

Unanswered questions about the Morris case linger, including why Skala didn’t transport Morris all the way to her West Philadelphia residence, Novak’s whereabouts during the “courtesy ride” and why neither officer responded to Morris at 16th and Walnut streets — where she was discovered by a passerby lying unconscious after a head injury.

Morris dispatch record never explained

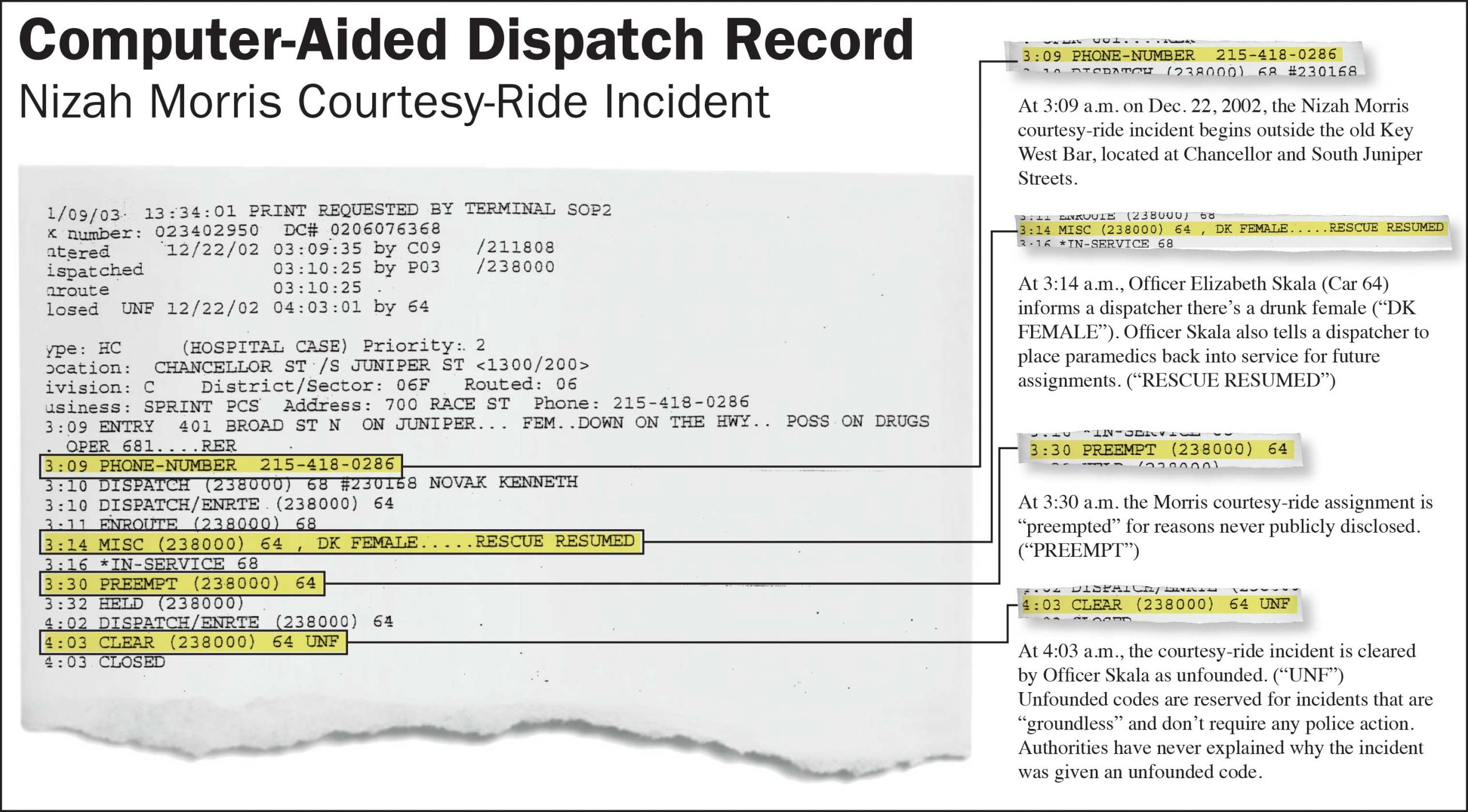

Over the years, local authorities have released numerous Morris documents in a piecemeal manner. Some raise more questions than they answer. One such document is a computer-aided dispatch record for the courtesy-ride incident.

The CAD record document transmissions over the city’s 911 system between a 911 caller, a dispatcher and Novak (Car 68) and Skala (Car 64). A 3:09 a.m. entry documents the initial 911 call regarding a female “[down] on the [highway] [possibly] on drugs.”

“RER” stands for rescue en route, meaning paramedics have been dispatched.

The 3:10 entry documents the time Novak and Skala were dispatched to investigate the situation. The next two entries document that the officers accepted their assignments.

The 3:13 entry documents that Skala arrived at Key West and found a “DK” female. “DK” is police jargon for a drunk person. Skala also informs the dispatcher that medics can be “resumed,” meaning they weren’t needed to assess Morris’ condition.

At 3:16, Novak informs the dispatcher that he’s back “IN-SERVICE,” meaning he’s resuming his normal patrol duties.

At 3:30 a.m., the 911 call is preempted, as documented by a “PREEMPT” code. Local authorities haven’t explained what caused the 911 call to be preempted. At 3:32, the call is placed on hold, as documented by the “HELD” code. At 4:02, Skala is placed back on the call and at 4:03 a.m., she closes the call as unfounded (“UNF”).

Based on 911 recordings obtained by PGN, when Skala closed the initial 911 call at 4:03 a.m., it was 38 minutes after a passerby placed another 911 call on Morris’ behalf at 16th and Walnut, where Morris was lying unconscious with a bleeding head wound.

Unfounded codes are reserved for calls where there are no grounds for a responding officer to take any action. Police directives state that an unfounded code is reserved for “[a] report of a criminal offense or a complaint or incident, which upon an initial inquiry by the responding officer(s), proves to be totally groundless in that no evidence, complaint, or witness(es) exists to reasonably believe that a criminal offense was attempted or had occurred or a complaint or incident exists. An assignment is never ‘unfounded’ when the responding officer(s) takes police action at a particular location.”

Skala was shown a copy of the dispatch record when she publicly testified before the Police Advisory Commission in December 2006. She had no explanation for the “PREEMPT,” “HELD” and “UNF” codes.

According to a hearing transcript, when then-PAC Commissioner Adam J. Rodgers asked Skala: “Can you explain what preempt means?” Skala replied: “I have no idea.”

On May 24, PGN asked the police department’s public-affairs office for an explanation of the unfounded disposition code on the Morris dispatch record. A spokesperson told PGN to submit the request to the city Law Department, which didn’t respond as of presstime.

Judge rules D.A.’s Office has Morris

911 recordings

Common Pleas Judge Abbe F. Fletman last week reversed a 2017 determination by the state Office of Open Records that the D.A.’s Office doesn’t have any Morris 911 recordings in its “possession, custody or control.” Fletman said the D.A.’s Office actually has a nine-page transcript of Morris 911 recordings provided to the office by PGN in 2009.

If left unchallenged, Fletman’s ruling is the first judicial declaration that the D.A.’s Office has nine pages of 911 recordings relating to the Morris incident, which she characterized as a “murder.”

PGN created the transcript from cassette tapes given to the paper by a private citizen shortly after Morris died. But several key 911 transmissions appear to be missing from the tapes. In 2008, PGN gave a copy of the transcript to the city Law Department to help reconstitute the police department’s Morris homicide file, which was lost in 2003.

In an 11-page opinion, Fletman noted that Assistant District Attorney Douglas M. Weck Jr. swore in an attestation that the D.A.’s Office doesn’t have any Morris 911 records in its possession, custody or control. Weck’s attestation resulted in the state Office of Open Records committing an error in 2017 by determining the non-existence of Morris 911 recordings at the D.A.’s Office, Fletman ruled.

But Fletman said the D.A.’s Office wasn’t required to provide a copy of the transcript to PGN because the paper’s open-records request is limited in scope to 911 recordings the D.A.’s Office received from police. She also said the paper shouldn’t file additional requests for Morris 911 recordings at the D.A.’s Office, noting that it already filed four such requests since 2006.