If you’ve never heard of the 1926 Sesqui-Centennial, an elaborate celebration of the 150th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence that took place in South Philadelphia, you’re not alone.

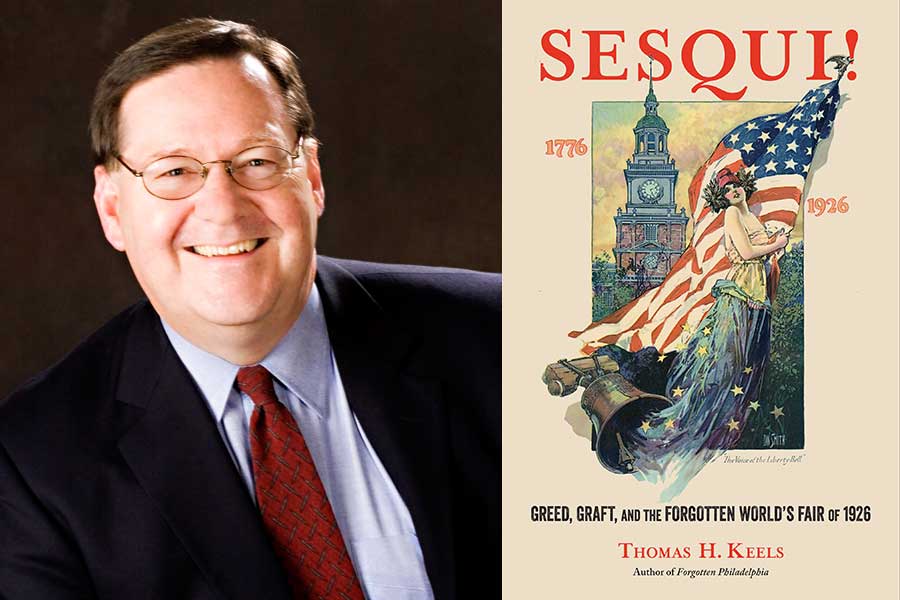

According to Thomas H. Keels, author of “Sesqui! Greed, Graft, and The Forgotten World’s Fair of 1926,” most people are unaware of it.

“I asked friends about it,” said Keels, who has written or co-authored seven books about local history. “Even people who were knowledgeable about Philadelphia didn’t know much about the Sesqui-Centennial.”

“Sesqui!” should help to dispel that ignorance. The book, a thorough examination of the fair, is written in a lively, engaging style and is copiously illustrated.

The basic facts about the Sesqui-Centennial are dismal. The fair ran from May-December 1926. During that time, it rained 107 out of 184 days. Event organizers estimated that the fair would draw about 45-million people; fewer than 5 million actually attended. Afterwards, the city claimed it had lost $10 million and the event’s governing body declared bankruptcy.

Why revisit such an obvious failure? The reason, Keels explained, is that we are still living with the cultural and political issues the Sesqui-Centennial raised.

“On the surface, ‘Sesqui!’ is about Philadelphia’s second world’s fair, which took place in South Philadelphia in 1926 and was one of the least successful world’s fairs,” he said. “But it’s really a book about politics and corruption and the pay-to-play culture that permeated the city and doomed the fair from the start.”

In the early 1920s, Philadelphia was firmly controlled by the Republican party, whose undisputed leader was William Vare.

“In the 1920s, Vare emerged as the most omnipotent political boss Philadelphia had ever known, ruling the city with an iron hand that reminded observers of Benito Mussolini,” Keels said.

Thanks to Vare’s influence, the Sesqui-Centennial was moved from the Parkway, where the city’s blue bloods and technocrats wanted it to take place, to the swamps at the southernmost tip of South Philadelphia.

At the time, Keels explained, the region was mostly pig farms and trash dumps. Vare grew up there and saw the Sesqui-Centennial as an opportunity to finally develop it. Unfortunately, by diverting resources to a section of the city that had virtually no infrastructure, he hijacked the Sesqui-Centennial and shortchanged the entire city.

The Sesqui-Centennial had other problems too. Racism, sexism and anti-Semitism marred the event. The most jaw-dropping example, Keels noted, is the fact that the Ku Klux Klan almost held a massive rally at the fair.

“At one point, the Sesqui was going to host 100,000 Ku Klux Klan members. They were going to march down Broad Street from City Hall to the Sesqui-Centennial and then burn a cross at the lake there,” Keels said.

“This was not something being done surreptitiously,” he added. “The mayor and fair manager invited them.”

Fortunately, Rabbi Louis Wolsey of Philadelphia’s Congregation Rodeph Shalom and others spoke out and the Klan rally was scrapped.

The Sesqui-Centennial had a few bright spots. The Palace of Fine Arts displayed more than 10,000 pieces and introduced Philadelphians to modern masters like Matisse and Picasso.

A prize fight between Gene Tunney and Jack Dempsey brought roughly 130,000 people to the Sesqui-Centennial Stadium, including Broadway impresario Flo Ziegfeld and actress Gloria Swanson.

The Sesqui-Centennial’s one indubitable success was “High Street of 1776,” an exhibit put on by women from some of the city’s most influential families. It recreated historical buildings and featured costumed reenactors.

“They were visionary in figuring out that you have to get people involved, engage them, not just show the piles of stuff, which is what most of the other exhibits at the fair were,” Keels said.

Their hard work paid off. According to Keels, High Street “got over 5,000 visitors every day while the rest of the fair was like an empty playground.”

In fact, Keels will give a talk on these remarkable women called “The Ladies of the Fair” April 22 at Historic Strawberry Mansion.

The author regularly lectures on various aspects of local history. And with seven books under his belt, including “Philadelphia’s Golden Age of Retail” and “Wicked Philadelphia: Sin in the City of Brotherly Love,” he has plenty of good stories to tell.

Another place Keels can be found is Laurel Hill Cemetery, which he calls “a favorite hangout of mine.” He’s been a tour guide there for more than two decades and has even helped stage plays on its grounds.

How does Keels manage all this, especially given that he holds down a full-time job in the health-care industry? The prolific author is quick to credit his husband, Lawrence Arrigale.

“I have to give him a huge shout-out, for this book as well as all the others. He’s been my editor, photographer, tech guy and much more. I could not have done any of this without him.”

From the sound of things, the couple won’t have much downtime. Keels is already thinking about his next book.

“It’ll be something completely different: a detective novel set in Philadelphia during World War II with a gay detective living within Philadelphia’s very-closed gay culture at the time.”

Sounds like a page-turner. We can’t wait to read it!

To keep up with Thomas Keels, visit www.thomaskeels.com.