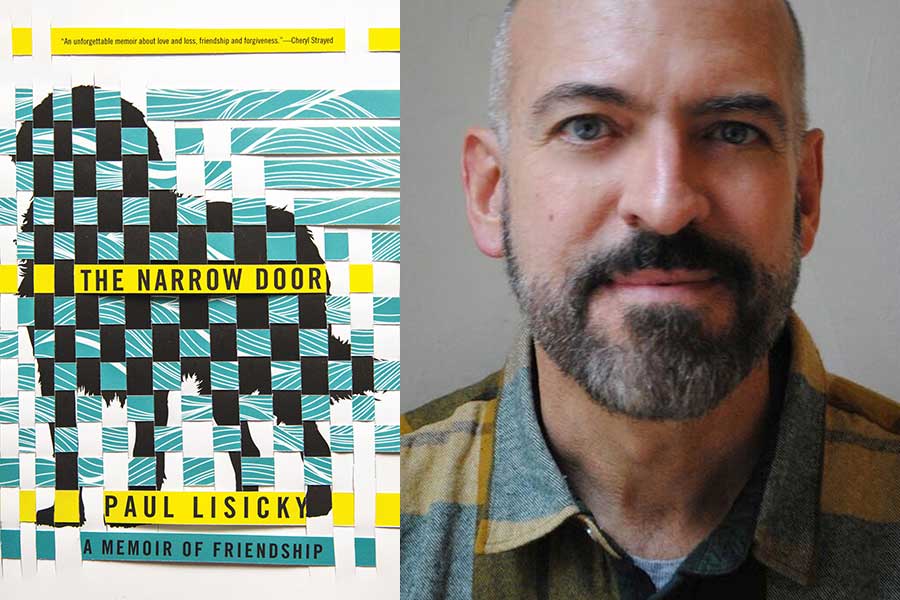

Local gay author Paul Lisicky is very busy these days. When he’s not teaching in the MFA program at Rutgers University-Camden, he’s on the road promoting his new memoir, “The Narrow Door.”

Lisicky’s fifth book is a deeply personal and sometimes painful account of his friendship with Denise Gess, a fellow writer who succumbed to cancer in 2009.

Graywolf Press published “The Narrow Door” in January. Ever since, Lisicky has kept up a grueling schedule. No sooner have classes finished on Wednesday afternoon than he’s off to another reading.

When we spoke by phone on a recent afternoon, Lisicky was in Portland for a reading at Powell’s Books, but he wasn’t stressed out about juggling teaching with a book tour. “I actually feel much more optimistic about managing it than I did before it all started,” he joked.

Fortunately for local book lovers, Lisicky will read at Big Blue Marble Bookstore, 551 Carpenter Lane, at 6 p.m. March 5. The event is free and includes another Graywolf author, Sara Majka.

Lisicky began jotting down impressions and memories about his relationship with Gess just six weeks after her death.

“Primarily, I was just writing to keep her in the world for myself,” he said. “I just wanted to record her thoughts and gestures; I wanted to see her face and hear how she laughed.”

The two met in the early 1980s as graduate students at Rutgers. Lisicky, a first-year teaching assistant, was an inexperienced writer trying to find his voice. Gess, a few years older, charmed her students and impressed her professors.

Gess was charismatic outside the classroom too. Attractive, intelligent and ambitious, she had plenty of male admirers. Lisicky, however, was deeply closeted. Still, the unlikely pair became fast friends. When they weren’t together on campus, they were chatting for hours on late-night phone calls. As Lisicky acknowledges in a passage regarding those days, “Listening to Denise is my real education.”

“The Narrow Door” isn’t a straightforward account of a friendship or a gossipy tell-all book, though. It’s a thoughtful examination of love, loss and friendship that refuses to simplify difficult subjects.

Lisicky keeps readers on their toes by declining to identify lovers and spouses, often accomplished authors themselves. This strategy, which Lisicky called “playful,” prevents these writers from overshadowing the book’s true focus: the 26-year friendship of Lisicky and Gess.

He also eschews a linear narrative. “The Narrow Door” is composed of a series of brief impressions and reflections, which jump back and forth in time and space. No sooner has Lisicky recalled some memory of Gess, than his thoughts drift or his reverie is interrupted by external events like the Deepwater Horizon oil spill.

The technique, disorienting at first, actually mirrors Lisicky’s experience in the year following Gess’ death.

“The structure of the book really wants to mimic or follow the experience of grief,” he explained. “Because grief does not move in 4/4 time: It’s not linear, it stops and starts, there are tangents.”

Lisicky is also disarmingly candid about Gess. She was a complex, contradictory figure. Despite her love and support, she was insecure and needed constant affirmation. At times, he writes, “it seemed to be that she was confusing volatility with authenticity.”

Lisicky is equally frank about himself. When he first meets Gess, for example, he is less an autonomous individual than a good boy who does what others expect of him. Recalling the mid-1980s, he writes, “I wanted to become myself, but there wasn’t even a self to work with.”

That changes in the due course of time. Lisicky comes out, gets published and marries Mark Doty, a well-respected gay author. Gess, however, seems stymied. Her first novel, “Good Deeds,” was well-received, but her editor was unhappy with the manuscript of her second novel and demanded changes. Tenure eluded her. Always competitive, Gess began to feel like she’d been shunted aside.

The nadir of their friendship comes when Gess visits Lisicky and his husband in North Carolina, where they are living temporarily during a teaching gig. When Lisicky mildly criticizes another writer’s work, Gess explodes. Her reaction is so extreme, so frightening, that both men wonder about her sanity.

“She’s a hurricane of woundedness,” he writes. Bitterness, he concludes, had changed her irrevocably.

This challenge to their friendship, and Gess’ cancer, are not the only painful issues Lisicky addresses. As he’s engulfed by sadness at her death, his marriage begins to unravel.

It would be wrong, however, for readers to think that disappointment, frustration and death are the predominant themes. Lisicky’s real subject is love.

After Gess’ blowup, the two don’t speak for a few months. Eventually, they reconnect, tentatively at first, but it seems as if they become closer than ever. Lisicky recalls visiting Gess after she’d been diagnosed with cancer. Sitting on the couch, she asks if she can rest her feet on his lap.

“Funny that it took us 26 years and cancer to get here,” he remarks. “Ease with each other’s body. It doesn’t matter anymore that she’s straight and I’m not. See how we’ve been a little bit in love all this time, and not able to say it?”

To learn more, visit www.paullisicky.net.