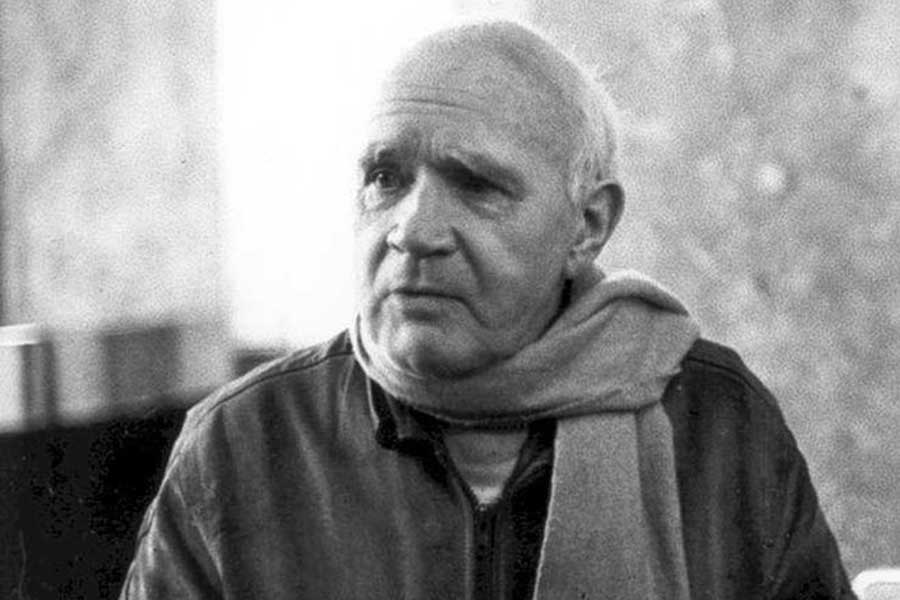

Jean Genet, the famous French author and political activist, could be jarringly honest.

“I said publicly that I was a queer, a thief, a traitor, cowardly,” Genet once told an interviewer who asked how he presented himself to the public.

Such unflinching candor repelled many people, but it also inspired a few, like photographer Moyra Davey.

On Dec. 3, Davey and a handful of colleagues will gather at International House Philadelphia for an evening of films and discussion devoted to Genet. A highlight of the program is a screening of Genet’s 1950 film “Un Chant d’Amour.”

In addition, Davey and four guests will read passages from Genet’s writing and discuss work inspired by him. Among her interlocutors are the feminist film theorist Kaja Silverman and the art historian Eric Rosenberg.

The program is co-sponsored by Penn’s Institute of Contemporary Art, which currently features the exhibition “Moyra Davey: Burn the Diaries.”

It promises to be a freewheeling event, which would no doubt appeal to the anarchic Genet.

“There’s a lot of potential to go in many directions and be surprising,” Davey said.

Genet’s personal story is as gripping as any novel. Born in 1910 to a young prostitute, he spent part of his youth in the notorious Mettray Penal Colony, where delinquents mixed with hardened criminals. As a young man he was a vagabond, hustler and petty thief.

Genet bounced in and out of jail from the late 1930s through the mid-1940s, but it was prison where he began writing. He soon produced a series of novels, among them 1949’s “The Thief’s Journal.” After suffering a spell of writer’s block in the early 1950s, he reinvented himself as a successful playwright, staging self-conscious, confrontational works like “The Balcony.”

By the late 1960s, Genet had transformed himself yet again, becoming a political activist. He always lent his support to underdogs, most notably the Black Panthers and Palestinian refugees. In 1986, after years of heavy smoking, he died from throat cancer.

Genet remains an important author, especially for young queers with a literary bent. Davey, who is straight and married, admits that she’s a relative newcomer to his work.

“I had never read Genet until I began this project a couple of years ago. I just kind of bumped up against him,” she said.

Davey’s encounter with Genet began during a panel discussion on photography and writing, when a colleague cited comments Genet made about art and private life. Intrigued, she tracked down the source and soon immersed herself in Genet’s essays, interviews and polemics.

“It was interesting for me to come to him much, much later in my life and to have this sort of intellectual — not just intellectual — but very visceral encounter with him, because he’s an incredibly visceral writer,” she said.

Davey found that Genet’s novels were not necessarily to her taste. Despite what she referred to as Genet’s abrasiveness, she was nonetheless drawn to his honesty and integrity.

“All the contradictions in his personality are so fascinating,” she said. “On one hand, he was kind of a saintly person; on the other hand, he was monstrous. To look at those two sides of him and try and reconcile them is a really interesting process.

Viewers can get a glimpse into that process by checking out her current exhibit at the ICA. Mixing photography, writing, and video, it offers one artist’s deeply felt response to the work of another.

On Wednesday evening, however, “Un Chant d’Amour” is likely to be the focus. Genet’s only film is a silent, black-and-white movie lasting fewer than 30 minutes. According to his biographer, the novelist Edmund White, it is “one of the most intense evocations in film of homosexual eroticism.”

The movie, set in a prison, revolves around an awkward, warped love triangle between two prisoners and their jailer. This incredibly erotic film, nonlinear and poetic, drifts between reverie and pornography, mixing tender imagery with depictions of shocking brutality.

Phallic symbols abound: a bouquet of flowers, cigarettes, a straw, even a handgun. Genet is not coy: He shows men masturbating and focuses his camera directly on naked cocks. Fellatio, sadism and voyeurism are all touched upon, but also longing and love.

According to White, the film’s subject matter and imagery were deemed pornographic, so it wasn’t screened in public until a few years after being made. In 1964, when the filmmaker and archivist Jonas Mekas showed it in New York City, he was beaten and arrested by police.

Fortunately, the police won’t be raiding International House for this screening. The real issue, though, is whether, like Moyra Davey, attendees can see beyond the provocation and make a connection with this dead, gay Frenchman and his confrontational art, despite differences of gender, politics and sensibility.

For more information about this event, visit http://ihousephilly.org/calendar/un-chant-d-amour-jean-genet-in-chicago.