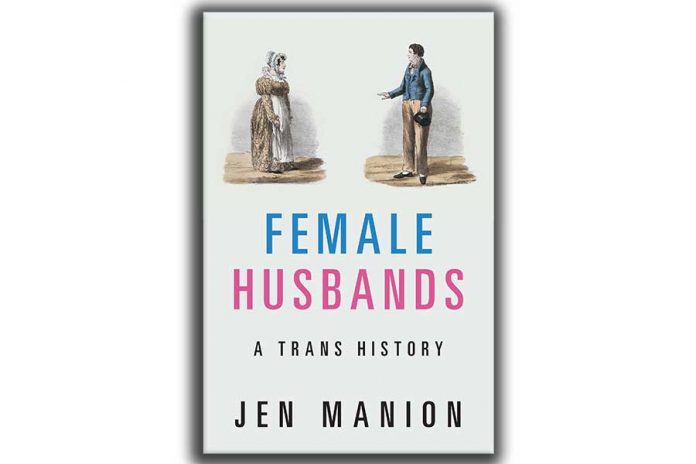

A new book is exploring an often forgotten and overlooked part of transgender history.

“Female Husbands: A Trans History” is a series of short biographies about people assigned female who lived as men, and married women from the 1740’s through the 1920’s. Written by Dr. Jen Manion, professor of history at Amherst College and graduate of Rutgers and the University of Pennsylvania, the book also explores the social, economic and political developments that influenced popular attitudes and treatment toward those couples during that time period, as well as the emergence of queer and gender non-conforming subcultures, women’s rights, and the strict regulation of marriage licenses that all led to the demise of the category of ‘female husband’ early in the twentieth century.

We talked to Manion about their new book and how these pieces of trans history fit into the socio-political landscape of the modern day.

PGN: How much time and effort went into researching this book and how did you first happen upon the subject matter?

JM: Quite a bit! I began research in 2013 when I had a National Endowment for the Humanities fellowship at the American Antiquarian Society. That gave me six months of full-time research to kick-start the project and get a sense of major trends in 19th century newspapers and magazines. I stumbled into “female husbands” when I was researching so called “female sailors,” who I have long been interested in. Digital newspapers are at the heart of the project but I also spent tons of time in traditional archives reading court records, prison logs, organizational reports, and newspapers that have not been digitized. I did a lot of old-fashioned sleuthing in government records to confirm biographical details such as birth, marriage, death, taxes, occupation – things like that. And I read hundreds of articles and books by other historians to establish context for the lives of female husbands.

PGN: What is the biggest revelation you came to in the process of researching for and writing this book?

JM: The most surprising and exciting thing was how widespread accounts of female husbands were. I’m from Pottsville, Pennsylvania—a small town 100 miles outside of Philadelphia—known for its rich deposits of anthracite coal. I was floored when I came across references to “female husbands” in early editions of The Miners Journal including cases from Manchester, England in 1838 and Syracuse, New York in 1854!

PGN: Why focus on the time period between 1746 and the start of World War I?

JM: The time frame really charts the rise and fall of “female husband” as a descriptor in the media to describe a certain group of people: someone assigned female, who transcended gender, lived as a man, and married a woman. The first person was described as such in the press in 1746 and it was picked up by other writers and editors. There were probably hundreds, possibly even thousands of other people who lived similar lives during this era but remained undetected or were seen in a slightly different light. By the turn of the twentieth century, the term “female husband” lost its meaning because it was used to describe all different kinds of people – including masculine presenting women and cisgender men who were not thought of as manly enough.

PGN: Do you think these corners of transgender history were more covered up by history or just forgotten and not chronicled?

JM: That is a really important question! I think a few things led to these important stories being buried for so long. Some of these accounts feature people we have known about for a long time, but historians viewed through the lens of feminism (as strong women) or lesbians (people who presented as men so they could be with female lovers). Transgender studies invites us to see them as people who were driven by a desire to transcend gender and live as men. That doesn’t mean they weren’t also strong and/or that some of them were not motivated by same-sex desire. These things aren’t mutually exclusive. But it is time for historians to embrace trans and nonbinary communities and write history in a way that recognizes and affirms rather than denies these experiences.

PGN: What can this generation of trans folk learn from the generations you documented in “Female Husbands?”

JM: Our community has a tremendous history and tradition to draw from not only for strength and inspiration but also for thinking critically about how society even conceptualizes sexual difference. This can inform how we advocate for trans rights and dignity in the present. Most of us are denied access to this knowledge from a young age and made to feel that we are alone and that our feelings are both new and atypical. We need more than just our personal experiences to educate people with – history can be a powerful tool for us as well as people we hope will become more informed allies and advocates.

PGN: Are there other eras of transgender history that you intend to explore and/or uncover with future book projects?

JM: So much transgender history remains to be written. I think everyone should get involved. Local community history archives such as the Wilcox Archives at William Way have wonderful records that anyone can use. Many newspaper records have been digitized and are available for free through the Library of Congress Documenting America Collection. The Digital Transgender Archive is a curated and free online source. I’ll probably stick to the nineteenth century because there is so much fun material that I haven’t been able to write about yet. We really need more people writing about the people and organizations at the heart of the transgender rights movement from the 1950s onward.

“Female Husbands: A Trans History” is available March 31 through Cambridge University Press. For more information visit https://jenmanion.com.