The Trump administration’s ban on transgender military members is expected to take effect. Thousands of service members will be forced to leave.

Finding a place to live will likely be the next step for people leaving the military, and My Brother’s House is gearing up. The nonprofit works to address the problem of veteran homelessness by providing housing and other necessary services.

Army veteran Dr. Remolia Simpson stated, “Our transgender veterans face more hardships because of biases due to ignorance and hate. They are now facing expulsion from the military, and continue to be discriminated against when it comes to securing safe housing and employment.“

Simpson started My Brother’s House three years ago for heterosexual and LGBTQ vets alike. Lesbian-identified Simpson served as far away as South Korea and West Germany from 1982 to 1988 before the “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy was implemented, meaning she was never able to be open about her sexual orientation. She is no stranger to the way legislation impacts the lives of LGBTQ soldiers.

My Brother’s House mission states, “We firmly believe that those who kept us living without fear on the battlefields and oceans of the world should be free from fear when they return to civilian life.” And Dr. Simpson articulates “We will do what is necessary to assist all of American’s veterans to find safe housing; we will provide crisis counseling, and assist with finding employment.

She hopes to bring awareness to the issues transgender veterans are facing in today’s political climate, and she emphasizes that My Brother’s House will “continue our fight against the war on homelessness among our nations’ heroes.”

An impassioned organization, My Brother’s House will no doubt aid local Philadelphian veterans in the crusade for stable housing, but currently My Brother’s House is in need of volunteers and donations.

A veteran has donated a home in the neighborhood of Mount Airy in Philadelphia that requires a lot of work. The four-bedroom, three-bathroom home needs $12,000 in order to transfer the deed, and about the same amount to pay back taxes. Fundraisers will soon be held at Toasted Walnut in Philadelphia and Havana Restaurant & Bar in New Hope to garner support.

Additionally, $60,000 is needed for repairs — roof to foundation, from sheet rock and paint to updating the kitchen and bathrooms. Dr. Simpson says the organization is attempting to secure grants from hardware stores to save money, though they plan to do most of the labor themselves.

“We are planning to attend as many Pride events this season to raise awareness and funding,” Dr. Simpson added.

An “official” grand opening of the Mount Airy Home is scheduled for May 19, which means the sooner funds can be raised, the better. If you or anyone you know can provide assistance, Dr. Simpson asks you be in touch as soon as possible.

My Brother’s House hopes to lease a second Philadelphia-area house, a six-bedroom, four-bathroom, in June, after completion of the Mount Airy home.

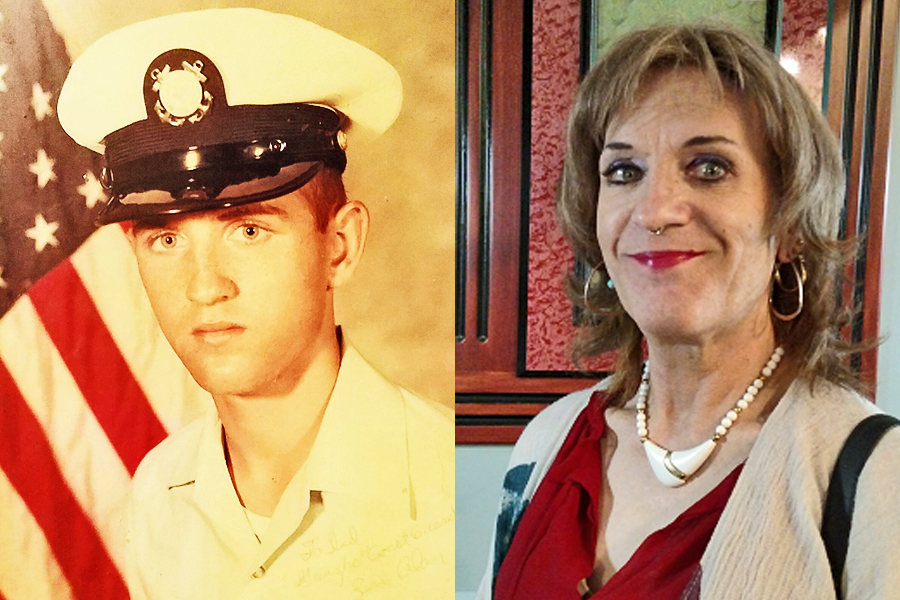

Transgender veteran, Alli-Beth Shinberg and her husband Max, a transgender man, live at the first My Brother’s House facility, in Easton, Pa. Shinberg left the Coast Guard in 1975 and is still suffering from trauma that occurred while she serving, and in the decades that followed.

Shinberg grew up in the Philadelphia suburb of Wyndmoor, as the oldest of three, with an affinity for David Bowie.

At age 17, a girlfriend convinced her to join the Coast Guard. Though the draft had ended, she had a Selective Service card and hoped to avoid Vietnam. During her time in the military she was taunted and sexually assaulted on numerous occasions. After enduring abuse, she was caught rolling joints and sentenced to 30 days to confined quarters but after only 15, she was discharged under honorable conditions; however, she was not recommended for reinstatement.

Shinberg spent the years after working gigs with rock bands and “having sex.” In the mid-1980s she took birth control pills, mostly estrogen, and noticed her face starting to change. She considered herself a dandy. In 1985 she had a child with a roommate of hers and married her, taking her mother’s advice. They divorced when her child was six.

Jobs came and went as Bowie remained in her life; “therapy” she said.

In 2005, Shinberg sought treatment at the VA due to a diagnosis of colon cancer. She claimed poor surgery meant losing her navel. Afterward, she became addicted to painkillers. Unable to work, she lost her home and suffered from unstable housing in the years that followed.

In 2016, she had an intestinal blockage that lead to further surgery. Around this time, she began using medical marijuana, partially to wean herself off of drugs and also due a lack of access to transgender-inclusive psychiatric care and other medical necessities. Now, she has a state-issued card.

Having lived through an additional marriage, more failed relationships and further medical trauma, Shinberg took to Grindr and met Max who was born in Russia but moved to the States soon after. Though the two had a significant age difference, they found connection. Max’s parents were critical of his lifestyle, and he only remains in contact with his mother. Shinberg has no connection with her family.

She married Max when he turned 21. Since then, the two have had trouble keeping apartments and spent time in extended-stay motels when they could afford it. Eventually, they found My Brother’s House and became the first family at its Easton location.

Shinberg, now 62, survives on VA benefits and takes medical marijuana for PTSD due to sexual trauma and her medical issues.

Details about My Brother’s House are at http://www.mbhouse.org and the organization encourages you to make contact if you can help in any way.